- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Health Policy and the NHS provides a thorough and up-to-date review of the changes in the structure and organisation of the health service. It focuses on how sucessive governments have approached problems of health care, their policy assumptions and the economic and political context of their decision making. Divided into four parts the text considers in turn: the foundations and framework of the NHS, policy issues within the NHS that dominated the government's policy agenda until the late 1980s, health and society and the critiques of health policy which developed in the late 1970s and 1980s, and new directions for health policy in the future.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Health Policy and the NHS by Judith Allsop in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

MedicineSubtopic

Health Care DeliveryFoundations and Framework

CHAPTER 1

Health policy and the politics of the NHS: an overview

This chapter aims to define some of the key terms used in this book. It goes on to examine a number of alternative theoretical models for providing health services. There then follows a general account of the characteristics of the NHS from 1948 to 1990, which has been referred to as a 'command and control' economy. The policies of health care within the NHS are then described. The chapter concludes with a summary of the social and economic changes which form a background to policy shifts within the NHS.

Key concepts and models of health care intervention

The key concepts used in the book are health, health policy, health services and health care, policy paradigms, the politics of the NHS and politics within the NHS. The models discussed are the market model, the professional model and the bureaucratic model of health care provision.

Health, health policy, health services and health care

Health can be defined in two ways. The focus can be on individual ill-health. Le Grand (1982) implicitly puts emphasis on the absence of illness in the following quotation:

Health affects every aspect of life. Our ability to work, to play, to enjoy our families and to socialise with friends, all depend crucially upon our physical well-being. Serious illnesses create enormous pain and suffering, even minor transient ailments can be depressing psychologically as well as debilitating physically. And ill health which leads to death makes all other services of satisfaction irrelevant.

(Le Grand 1982: 23)

Alternatively, emphasis may be placed on protecting the health of populations. This is summed up in a quotation from the 1974 report on The Health of Canadians (the Lalonde Report) which declares:

Good health is the bedrock on which social progress is built. A nation of healthy people can do those things which make life worthwhile and as the level of health increases so does the potential for happiness.

(Ministry of National Health and Welfare (Canada), 1974: preface)

Both these quotations suggest why governments may develop policies for health: whether these are to protect individuals from the devastating effects of loss of income through illness and the high cost of health care; or, whether these focus on social and health policies which allow the maintenance of health and protection from the hazards and threats which might damage it. Indeed, governments may be voted into office to take actions in these respects.

The term 'health policy' has been limited mainly to the policies of governments. That is, to the authoritative statements of intent about action which relate to the maintenance of good health in individuals and populations; the cure of disease and illness; and the care of the vulnerable and frail. Other institutions in society also make statements about health. Although these are referred to, the assumption is that as government has the ultimate authority to act, it is their policies which become a focus for debate and action.

An alternative view is that policy, far from being encapsulated in statements of intent, is the consequence of the actions taken by individuals in the process of implementation (see Barrett and Fudge 1981). In other words, in the process of implementation, policy becomes translated into something quite different from what was intended; what policy is can only be seen in terms of outcomes. The view taken here is that the policy process is cyclical. Government statements of intent have been taken as the main starting point. In being implemented, policies may be, and indeed often are, distorted by the interpretations, actions or inertia of lower-level actors. Such distortions reflect the relative power of individuals or groups. This aspect of policy is discussed later in this chapter. It is therefore particularly difficult to determine policy outcomes; research or evaluation is often required of government policies boldly stated in official documents.

The term 'health services' refers to the type and range of facilities provided by health professionals and agencies. This can be sub-divided further - thus, there are mental health services, primary care services or acute hospital services and so on. And 'health care' is taken to be the result of activities undertaken by individual health workers within various organisations.

Policy paradigms

Rein (1976) suggests that a policy paradigm is based on a particular view of the essential problem to be solved.

It is a working model of why things are as they are, a problem-solving framework, which supplies values and benefits, but also procedures, habits of thought, and a view of how society functions. It often provides a guiding metaphor of how the world works which implies a general direction for intervention, it is more specific than an ideology or a system of beliefs, but broader than a principle of intervention.

(Rein 1976: 103)

Rein goes on to suggest that policy paradigms are a 'curious mixture of psychological assumptions, scientific concepts, value commitments, social aspirations, personal beliefs and administrative constraints'. In order to shift, they must be challenged by an alternative view of the world which appears to fit current problems better.

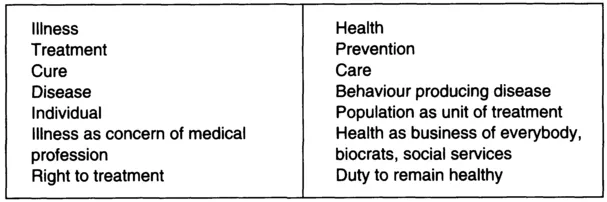

Within health policy, there can be any number of policy paradigms. One which reflects different conceptions of health has already been referred to above. Government policies may focus on the care or treatment of illness in individuals and on personal illness services and/or on the maintenance and promotion of health in individuals or populations. This will have a profound effect on what problems are identified, on the way services are provided, who are considered to be the authoritative providers and who is deemed to be the main object of policy. Figure 1.1 illustrates the implications of a paradigm shift from an illness-based to a preventive model.

Figure 1.1 Shift in emphasis in the conceptualisation of health and illness

Source: Illsley, R. (1977) Health and Health Policy.

Source: Illsley, R. (1977) Health and Health Policy.

A further paradigm shift can be illustrated in relation to the care of people with special needs. For example there has been a shift in relation to ideas about delivery - from institutional care to community care or, more recently, from a monopoly supplier to a number of competitors. Within medical care there are three theoretical options for supplying a service.

Models for the supply of medical services

Models are simply constructs of possibilities which rarely exist in any pure form. If it is assumed that all individuals will need medical care during their lifetime and there is no such thing as perfect health, access to the best possible care for those who are ill is of fundamental importance. This may be supplied according to a market, a professional or a bureaucratic model.

A market model assumes that health care is a product like any other. Where a demand exists, then market forces will supply the goods required for a price. Market theory suggests that suppliers, as individuals or corporations, will harness available technologies to provide health care relative to demand from users for that price. Suppliers will advertise their wares while competition will ensure a price which gives a margin of profit and that consumer preferences are met. In theory the consumer is sovereign while the 'hidden hand' of market forces ensures the most efficient use of scarce resources by matching supply and demand. In this context, the market has the authority to determine resource allocation.

However, particularly since the rise of medical science in the nineteenth century, two other models have developed - the professional and the bureaucratic models. Both these assume medical care is too important and knowledge too specialised to be treated as a market good. The professional model places authority over medical care with the expert - the doctor. Because it is based on technical and expert knowledge, those who need medical care must be protected from unqualified practitioners. This may include the authority to determine training and qualifications and to judge what is in the interest of the patient. The approach is essentially paternalistic. Although in modern states, arrangements may be made to ensure access to doctors for the whole population, the medical profession remains dominant in determining the shape of the health care system.

In the bureaucratic model, the state takes over the role of determining health policy. This tends to be encouraged by the democratic process as governments represent the interests of citizens who collectively put a high value on health care. In this model, the emphasis is on the rights of citizenship and the state becomes involved in distributional issues such as: ensuring access to services according to equity criteria; the allocation of resources; the management of services and the ordering of priorities. The benefits to the collectivity as well as to the individual are stressed.

In actual welfare or health states, governments mediate between the market and the professional providers in a variety of different ways. For example, Titmuss (1958) referred to the residual, occupational and institutional-redistributive models of welfare. In the residual model, the family and the market were the main props for welfare, the state had a minor role in supporting the poor. In the occupational model, the employer and the fiscal system provided the major share of welfare. While in the institutional-redistributive model the state intervenes to provide redistribution benefits through the tax system. Epsing Anderson (1990), although he does not refer to health as such, discusses the liberal, corporatist-statist and socio-democratic welfare state models.

In the UK until the 1980s, the dominant model has been institutional-redistributive. By democratic mandate, a bureaucractic, centrally controlled system of health care was introduced in 1948. The choices made by government on behalf of the population are legitimised by government's representative character. At the same time, because of the dominance of scientific medicine, this still results in a powerful medical profession. Elston (1991) describes the cultural (the high value given to medical knowledge) and social (medical dominance in the division of labour) authority of medicine and the high degree of professional autonomy it enjoys. This forms part of the NHS 'command and control' economy described in more detail below.

Health care politics and the politics of the NHS

It has been argued that because scientific medicine has dominated health care provision in most modern welfare states, there is a typical form of health care politics. Conflicts and struggles for ascendency in relation to both policy and provision occur between structured interests configured around the state, the medical profession and, in some countries, health care funders and commercial interests.

For example, Alford (1975) suggests that interests in health care can be classified into three major groupings: the professional monopolisers, the corporate rationalisers and the community interest. These interest groups have certain aims and objectives and their power is structured in particular ways. The dominant interest group, he argues, contains the professional monopolisers - doctors whose control of medical knowledge both explains and reinforces the dominance of the disease model of illness. Although numerically small, in contrast to for example nurses, their definitions of health and illness tend to dominate health policy and provision. Alford comments:

Physicians have extracted an arbitrary set from an array of skills and knowledge relevant to the maintenance of health in a population and have successfully sold these as their property for a price and have managed to create legal mechanisms which enforce that monopoly and the social beliefs which mystify that population about the appropriateness and desirability of that monopoly.

(Alford 1975: 197)

The second major interest group is composed of 'the corporate rationalisers'. This includes politicians, administrators at central and local level, and some professionals whose main objective is to achieve greater coordination and integration in the planning and delivery of health services. Their interests lie in improving efficiency and effectiveness and making the best use of the health resources of the collectivity.

The third interest group identified by Alford is 'the community interest'; that is, the cluster of organisations and individuals which seek to represent a different order of priorities, alternative perspectives on health policy and perhaps a broader view of health care. They attempt to influence health policy through a variety of means, from lobbying the legislature to picketing local hospitals. In most health systems, community interests tend to be suppressed. The major forces of authoritative decisions are the professionals and government Ministers and officials who make decisions behind closed doors.

The politics of the NHS

On the basis of the above or similar types of analysis, it has been argued that the politics of the NHS are essentially concerned with the relationships between the two powerful interest groups, the government and the medical profession. Indeed, it has been argued that UK health politics is corporatist in style. That is, health policy is developed by the government and the medical profession, achieved by negotiation and compromise away from public scrutiny (Cawson 1982).

Harrison, Hunter and Pollitt (1990) review approaches to policy-making in the NHS and conclude that a version of the corporatist thesis, a process of what they call 'mutual partisan adjustment', occurs. In other words, the various structured-interest groups adjust to each other in shaping policy within a framework of accepted conventions. The model is reproduced in Document 7 (page 296). It may be of course, that this particular explanation of policy-making applied specifically to mainstream policies within the NHS between 1946 and 1990. This issue is addressed in Chapter 13.

The corporatist approach tends to take an over-simple view of health care politics with little recognition that the political interplay of groups may vary. Empirical studies suggest diversity. For example, Mills (1993) in a collection of studies on preventive health policy, shows that a variety of interest groups seeks to put pressu...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part One Foundations and Framework

- Part Two Policy Issues in the NHS

- Part Three Health and Society

- Part Four New Directions for Health Policy

- Part Five Documents

- Appendix 1 Health and Social Services Secretaries and Ministers

- Appendix 2 List of reports and statutes 1858-1994

- Select bibliography

- Index