![]()

Chapter 1

Why Measure Rural Livelihoods and Environmental Dependence?

Arild Angelsen, Helle Overgaard Larsen, Jens Friis Lund, Carsten Smith-Hall and Sven Wunder

There is in my opinion a right way and we are capable of finding it.

Albert Einstein (1954, Ideas and Opinions, Crown Publishers, New York)

The hidden harvest

Measuring rural livelihoods and environmental dependence is not straightforward. Environmental resources are important to millions of poor households in developing countries, yet there is not an established right way to systematically collect data that convey their importance. Such resources, harvested in non-cultivated habitats ranging from natural forests to rangelands and rivers, often contribute significantly to households’ current consumption, provide safety nets or pathways out of poverty. The uncertainty regarding the numbers can easily lead to either under-or overestimations (Angelsen and Wunder, 2003). Environmental income often consists of many different and sometimes irregularly collected resources: the forest fruits picked during herding, the medicinal plants collected when grandfather was sick, last month’s particularly rich fish catch, and so on. A myriad of resources gathered from multiple sources makes environmental income much harder to recall and quantify than a single annual corn or sorghum harvest. A high share of environmental resources are not traded in markets but consumed directly, further complicating their valuation. The body of literature quantifying environmental resources in rural livelihoods is slowly increasing (for example, Cavendish, 2000; Fisher, 2004; Mamo et al, 2007; Vedeld et al, 2007; Narain et al, 2008; Babulo et al, 2009; Kamanga et al, 2009), but has yet to be widely acknowledged in rural development circles – as becomes evident from recent reviews of rural income and livelihood studies that exclude environmental income (for example, Ellis and Freeman, 2005a).

The general shortage of a representative sample of studies, coupled with the diversity in the quality and methods used in the few existing ones, leave key questions unanswered: how important are environmental resources for poverty alleviation in quantitative terms? When they are important, is it because they can help lift the poor out of poverty or are they mainly useful as gap fillers and safety nets preventing extreme hardship? How do different resource management regimes and policies affect the benefits accruing to the poor? Answers to such questions are essential to design effective policies and projects to alleviate rural poverty. Yet, there is surprisingly little systematic knowledge to answer them adequately.

Published and unpublished quantitative environmental income studies are hard to compare due to methodological differences. In a summary of 54 studies on household environmental income, Vedeld et al (2004, pxiv) noted: ‘The studies reviewed displayed a high degree of theoretical and methodological pluralism, and the substantial variability in reporting of specific variables and results is partly explained through such pluralism. This variability must, however, also be attributed to methodological pitfalls and weaknesses observed in many studies.’ Methodological challenges include: (a) data generated using long (for example, one-year) recall periods, which is likely to seriously underestimate environmental incomes derived from a myriad of sources (Lund et al, 2008; see also Chapter 7); (b) inconsistent key definitions, for example, what is considered a forest or how income is defined, may differ across studies, making findings incomparable; (c) a host of survey implementation problems, such as failure to adequately train enumerators or check data while in the field, resulting in questionable data quality; and (d) a widespread perception that it is too difficult and costly to obtain high quality environmental income data. The geographical coverage of available studies is also limited, with most coming from dry southern and eastern Africa. Thus, while our knowledge regarding environmental income and rural livelihoods is incrementally improving, we believe that more in-depth studies across a range of sites are required, preferably using best-practice and unified methodologies that enable comparison and synthesis. This book is designed to be an instrument to help make it happen.

Designing and implementing household and village surveys for quantitative assessment of rural livelihoods in developing countries is challenging, with accurate quantification of income from biologically diverse ecosystems, such as forests, bush, grasslands and rivers, being particularly hard to achieve. However, as the above published studies indicate, this ‘hidden harvest’ (Scoones et al, 1992; Campbell and Luckert, 2002) is too important to ignore. Fieldwork using state-of-the-art methods and, in particular, well-designed household questionnaires, thus becomes an imperative to adequately capture environmental income dimensions of rural welfare. In fact, current poverty alleviation strategies in most developing countries draw to a significant extent on results from household surveys; environmental income estimates are, however, often not included in the standardized living standards measurement surveys (Oksanen and Mersmann, 2003). Studies based on such surveys are thus inadequate for understanding the diversity of rural income generation in developing countries.

One attempt to overcome this shortage of data is a large global-comparative research project: the Poverty Environment Network (PEN), described later in this chapter. The book draws widely on the methodological experiences from PEN.

Purpose of this book

This book aims to provide a solid methodological foundation for designing and implementing household and village surveys to quantify rural livelihoods, with an emphasis on quantifying environmental income and reliance in developing countries. All the major steps are covered, from pre-fieldwork planning, in-the-field sampling, questionnaire design and implementation, to post-fieldwork data analysis and result presentation. The intention is to provide input to the entire research process, in the specific context of developing and implementing operational research ideas using quantitative approaches in developing countries, while limiting the ‘remember the malaria pills’ and ‘get to know the local culture’ generalized advice that is covered well in other books.

The book is aimed at: (a) graduate students and researchers doing quantitative surveys on rural livelihoods, including (but not limited to) the environment, and (b) practitioners in government agencies, international aid agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) involved in fieldwork in relation to project implementation (for example, baseline and impact studies) in developing countries.

The book relates to three broad groups of literature: (a) the limited body of works at the graduate student level on broad field methods and introductions to the practicalities of fieldwork (for example, Barrett and Cason, 1997; Scheyvens and Storey, 2003); (b) the extensive literature on quantitative surveys in general, including work on business research methods (for example, Bryman and Bell, 2003) and measurement of living standards (for example, Grosh and Glewwe, 2000); and (c) the emerging body of literature on livelihoods in developing countries (for example, Ellis, 2000; Ellis and Freeman, 2005b; Homewood, 2005).

This book has four major distinctive features in relation to this pre-existing body of knowledge. First, it fills a gap between the three types of literature by giving a thorough review of using quantitative methods in rural livelihoods studies in developing countries. Second, it deals not only with quantitative household and village surveys, but covers the entire research process, as opposed to books focusing on methods (for example, Foddy, 1993), analysis of survey data (Deaton, 1997), fieldwork practicalities (for example, Barrett and Cason, 1997) or livelihood case studies (for example, Homewood, 2005). Third, it centres on rural livelihoods with environmental dependence as the predominant example of how to deal with livelihoods complexity, as opposed to other approaches that focus on issues such as health, education and agricultural income while disregarding information on environmental incomes (for example, Grosh and Glewwe, 2000). Fourth, as explained in the next section, it draws on the extensive comparable experiences in the PEN project of more than 50 researchers who have implemented and supported quantitative household and village surveys across a variety of continents, countries and cultures.

The Poverty Environment Network (PEN)

PEN is an international network and research project on poverty, environment and forest resources, organized by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). It was established in 2004 in order to address the environmental income issues identified in the introduction to this chapter, which have particular relevance for natural forests. The core of PEN is a tropics-wide collection of uniform socio-economic and environmental data at the household and village levels, undertaken by 33 PEN partners (mainly PhD students) and supported by some 20 PEN resource persons (CIFOR researchers, associates and external university partners acting as supervisors with active field presence), jointly generating a global database with more than 9000 households from 25 countries. The PEN project is arguably the most comprehensive study done in the field of poverty and environment, and will serve as the basis for the first global-comparative and quantitative analysis of the role of tropical environmental resources in poverty alleviation. This book is written by PEN partners and resource persons who have been involved in the design and implementation of PEN, as well as dozens of other projects collecting similar data.

PEN is built on the observation that some of the best empirical data collection is done by PhD students: they often spend long periods in the field and personally supervise the data collection process, thereby getting high quality data – something that established university researchers often lack the time to achieve. The basic PEN idea was to achieve two goals: (a) use the same ruler (same questionnaires and methods) to make data comparable, and (b) promote good practices and thus increase the quality of data. In short, the value added of the individual studies can be substantially enhanced by using standardized and rigorous definitions and methods, which permit comparative analysis.

The first phase of PEN from 2004 to 2005 focused on identifying and designing the research approach and the data collection instruments and guidelines, and at the same time building up the network through PEN partner recruitment. Fieldwork and data collection by PEN partners started in 2005. After completion in 2009, a third phase of data cleaning, establishing the global data set, data analysis and writing began. The project is expected to be completed in 2012, and the PEN data set will eventually be made publicly available for use by researchers.

The PEN research approach

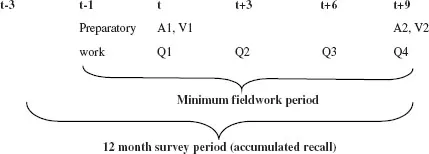

During early discussions and workshops, a consensus quickly emerged that, in order to get reliable estimates of environmental resource uses, a detailed recording (income accounting) method was needed, using short recall periods – one year being far too long for the accuracy aimed for. This was particularly inspired by work done in Zimbabwe by Cavendish (2000) and Campbell et al (2002). It was also decided that PEN data collection should consist of three types of quantitative surveys (in addition to an attrition and temporary absence survey) covering a full year:

• Two village surveys (V1, V2).

• Two annual household surveys (A1, A2).

• Four quarterly household surveys (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4).

The timing of the surveys is shown in Figure 1.1. Data collection requires a fieldwork period of no less than ten months. The village surveys (V1–V2) collect data that are common to all households, or show little variation among them (cf. Chapter 6); V1 is done at the beginning of the fieldwork to get background information on the villages, while V2 is done at the end of the fieldwork period to get information for the 12 months of accumulated recall period covered by the surveys. The household surveys were grouped into two categories: (a) annual household surveys, with A1 at the beginning of fieldwork providing household information serving as a baseline (demographics, assets, forest-related information), while A2 at the end collected information for the 12 month period covered by the surveys (for example, on risk); and (b) the four quarterly household surveys that focused on collecting detailed income information. All research tools (the prototype questionnaires and the associated technical guidelines; the template for data entry; the codebook; and the data cleaning procedures) can be downloaded from the PEN website (www.cifor.cgiar.org/pen). Prototype questionnaires are available in English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese, Indonesian, Nepalese and Khmer. While PEN pursued a common methodology, all prototype questionnaires were pretested and adapted to local conditions at each research site. Each PEN partner submits his/her final data set, along with a narrative adhering to a standard template and providing detailed contextual site information, to the global database.

Figure 1.1 The timing of village and household surveys in a PEN study

A key feature of the PEN research project is the collection of high quality data through the quarterly household surveys. These include detailed data collection on all types of income, not just environmental sources. In addition to the higher accuracy and reliability of quarterly income surveys, various income-generating activities often have considerable seasonal variations, and documenting these can help us understanding fluctuations and seasonal gap fillers. The recall period in the quarterly income surveys was generally one month, which would then be extrapolated to the three-month period. The exception was agricultural income and ‘other income’ (remittances, pension, and so on) that used three months, as these are major income sources (easier to remember) and might be irregular (thus the full 12-month period is covered). The PEN technical guidelines also emphasize that all major products with irregular harvesting, for example, short-lived mushrooms harvested for sale on a large scale or the occasional sale of a timber tree from private land, should be identified early on, for example, during preparatory fieldwork and pretesting of questionnaires. A one-month recall in quarterly surveys entails the risk of missing out on these activities, thus a three-month ...