![]()

Section III

Social and cultural psychology

![]()

14 Cognition and perception: East and West

Richard E. Nisbett

I would like to argue that, for the past 2500 years at least, Asians and people of European culture have had very different ways of understanding – even of seeing – the world around them (Nisbett, 2003; Nisbett, Peng, Choi, & Norenzayan, 2001). Western perception and cognition from the ancient Greeks forward has been analytic: the focus is on some central object (which could be a person) with respect to which the individual has some goal. The attributes of the object are attended to with the intention of categorizing it so that rules can be applied that will allow for prediction and control. Eastern perception has been holistic: the object or person is seen in a broad context or field and behavior is understood in terms of relationships and similarities rather than generalized categories and rules.

Ancient Greek and Chinese philosophy and science illustrate the dramatic differences in thought and perception (Cromer, 1993; Fung, 1983; Lloyd, 1990, 1991; Munro, 1969; Nakamura, 1964/1985). Aristotle’s physics focused almost exclusively on the object. A stone placed in water falls because it has the property of gravity; a piece of wood floats because it has the property of levity. In contrast, Chinese conceptions of action took into account the interaction between the object and the surrounding field. The concept of action at a distance was understood by the Chinese almost 2500 years before it was understood in the West. For example, the Chinese had substantial knowledge of magnetism and acoustics and understood the true reason for the tides (which escaped even Galileo).

Most Greek philosophers and scientists regarded objects as being composed of particles or atoms, whereas the Chinese saw matter as substances in wave form. Because the Greeks had a belief in rules governing categories of objects, they had a sense of control over the world. In contrast, the Chinese did not have an elaborate set of rules to explain the behavior of objects and did not experience the world as being as controllable as did the Greeks.

What might explain these radical differences in thought and perception? In my view it has to do with the nature of Chinese vs. Greek societies. Chinese society was based on agriculture and required substantial cooperation at the family and village level. Substantial interdependence or collectivism was the result. Confucian philosophy both codified and encouraged the following of elaborate rules governing social existence, which was hierarchically arranged. Greek society was based on occupations such as herding, fishing and trade that allowed for more independence or individualism.

Why might these social differences have prompted different views of the world? This could be because the Chinese social system encouraged viewing the world as complex and dependent on relationships whereas the Greek social system allowed for focus on objects (including of course social objects) with respect to which the individual had goals. The Chinese and Greeks were attending to different aspects of the social world and this might have prompted different cognitions and perceptions about it – holistic in the case of the Chinese and analytic in the case of the Greeks. The different understandings of the social world would have resulted in different understandings of the physical world, because, as Markus and Kitayama put it, if “one perceives oneself as embedded within a larger context of which one is an interdependent part, it is likely that other objects or events will be perceived in a similar way” (Markus & Kitayama, 1991b, p. 246).

If this social-origins account of divergent Chinese vs. Greek thought is correct, then it has implications for cultural differences in the cognition of ordinary people today. East Asians in general remain much more interdependent in their social lives than are Americans and other Westerners (Fiske, Kitayama, Markus, & Nisbett, 1998; Hsu, 1953, 1981; Markus & Kitayama, 1991a, 1991b; Triandis, 1989, 1995). Anthropologist Edward T. Hall (Hall, 1976) used the concept of “low context” vs. “high context” societies to describe differences in social relations. Westerners regard themselves as possessing traits, abilities, and preferences that are unchanging across social contexts. But East Asians view themselves as being so connected to others that who they are depends on the context. As philosopher Donald Munro put it, East Asians understand themselves “in terms of their relation to the whole, such as the family, society, Tao Principle, or Pure Consciousness” (Munro, 1985; Shih, 1919). If an important person is removed from the individual’s social network, that individual literally becomes a different person.

These differences in self-perception are captured by self-descriptions. When Americans and Canadians are asked to describe themselves, they mention their personality traits and attitudes more than do Japanese, who are more inclined to mention relationships (Cousins, 1989; Kanagawa, Cross, & Markus, 2001). North Americans tend to overestimate their distinctiveness and to prefer uniqueness in themselves and in their possessions (Markus & Kitayama, 1991b). In one clever study, Koreans and Americans were given a choice among different colored pens to have as a gift. Americans chose the rarest color whereas Koreans chose the most common color (Kim & Markus, 1999).

Socialization for independent vs. interdependent roles begins very early. Western babies often sleep in a different bed from their parents (or even in a different room), but this is rare for Asian babies. Adults from several generations often surround the Chinese baby, and the Japanese baby is almost always with its mother. When American mothers play with their children, they tend to focus their attention on objects and their attributes (“See the truck; it has nice wheels”), whereas Japanese mothers emphasize feelings and relationships (“When you throw your truck, the wall says, ‘Ouch’”) (Fernald & Morikawa, 1993). Koreans are better able to judge an employer’s true feelings about an employee from ratings of the employee than are Americans (Sanchez-Burks, Lee, Choi, Nisbett, Zhao, & Jasook, 2003). And when Masuda and Nisbett (2001) showed participants videos of fish, they found that Japanese were more likely to see emotions in the fish than were Americans.

These social differences, along with their implications for a sense of control, have been pointed out by L.-H. Chiu (Chiu, 1972):

Chinese are situation-centered. They are obliged to be sensitive to their environment. Americans are individual-centered. They expect their environment to be sensitive to them. Thus, Chinese tend to assume a passive attitude while Americans tend to possess an active and conquering attitude in dealing with their environment.

(p. 236)

[The American] orientation may inhibit the development of a tendency to perceive objects in the environmental context in terms of relationships or interdependence. On the other hand, the Chinese child learns very early to view the world as based on a network of relationships; he is socio-oriented, or situation-centered.

(p. 241)

If contemporary Asian and Western societies are different in their emphasis on relationships vs. independent action, then it might be the case that Asians and Westerners differ in their cognitive and perceptual habits along the lines of the holistic vs. analytic stance characteristic of ancient Chinese vs. ancient Greek science and philosophy. (By Asia I mean those East Asian countries in the Confucian tradition originating in China including China, Japan and Korea. By the West I mean Europe and many of the present and former members of the British Commonwealth including the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.) For the past several years, my colleagues and I have been examining the possibility of cultural differences in a number of cognitive and perceptual domains.

Cognitive differences

We find that East Asians and Westerners differ in the way they make causal attributions and predictions, in categorization based on rules vs. family resemblance and in categorization based on shared taxonomic labels vs. relationships.

Causal attribution

We might expect that Westerners, like ancient Greek scientists, would be inclined to explain events by reference to properties of the object and that East Asians would be inclined to explain the same events with reference to interactions between the object and the field. There is much evidence indicating that this is the case (for reviews see Choi, Nisbett, & Norenzayan, 1999; Norenzayan, Choi, & Nisbett, 1999; Norenzayan & Nisbett, 2000). Morris and Peng (1994) and Lee, Hallahan, and Herzog (1996) have shown that Americans are inclined to explain murders and sports events respectively by invoking presumed traits, abilities, or other characteristics of the individual, whereas Chinese and Hong Kong citizens are more likely to explain the same events with reference to contextual factors, including historical ones. Cha and Nam (1985) and Choi and Nisbett (1998) found that East Asians used more contextual information than did Americans in making causal attributions. The same is true for predictions.

Explanations are different even for events involving animals and inanimate objects. Morris and Peng (1994) showed participants cartoon displays of an individual fish moving in relation to a group of fish in various ways. Chinese participants were more likely to see the behavior of the individual fish as being produced by external factors, namely the other fish, than were Americans, whereas American participants were more inclined to see the behavior as being produced by factors internal to the individual fish. Peng and Knowles (2003) showed that for ambiguous physical events involving phenomena that appeared to be hydrodynamic, aerodynamic, or magnetic, Chinese were more likely to refer to the field when giving explanations (e.g., “the ball is more buoyant than the water”) than Americans were. The differences in causal attribution therefore probably reflect deep metaphysical differences that transcend specific rules about particular domains that are taught by the culture. In many of the causal attribution studies, incidentally, it could be shown that the East Asian tendency to prefer context was more likely to result in a correct analysis than was the American preference for the object.

Categorization

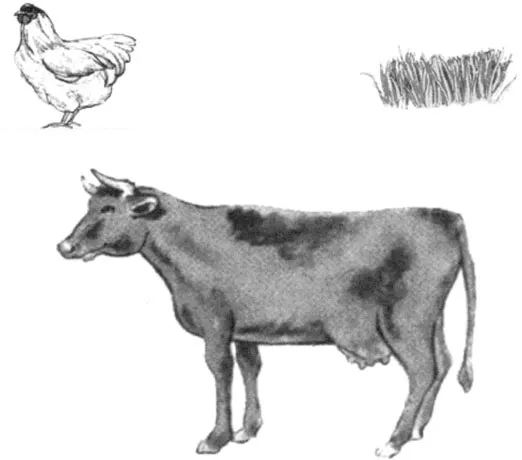

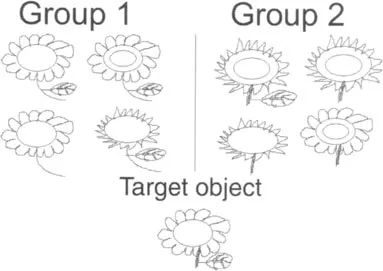

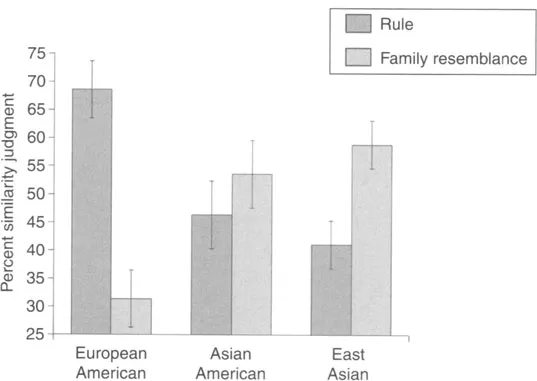

East Asians have been found to classify objects and events on the basis of relationships and family resemblance whereas Americans classify on the basis of rule-based category membership. Liang-Hwang Chiu (1972) showed triplets of objects like those in Figure 14.1 to Chinese and American children and asked them to indicate which of the two objects went together. American children put the chicken and the cow together and justified this by pointing out that “both are animals.” Chinese children put the cow and the grass together and justified this by saying that “the cow eats the grass.” Our research group has found the same sort of differential tendency in college students given word triplets to read (Ji, Zhang, & Nisbett, 2004). For example, Chinese and American participants were asked to indicate which two of the following three go together: notebook, magazine, pen. Americans tended to put the notebook and the magazine together because both have pages. Chinese tended to put the pen and the notebook together because the pen writes on the notebook. Norenzayan and his colleagues asked participants to report whether a target object like that at the bottom of Figure 14.2 was more similar to the group of objects on the left or the group on the right (Norenzayan, Smith, Kim, & Nisbett, 2002).The target object bears a strong family resemblance to the group of objects on the left, but there is a rule that allows placing the object in the group on the right, namely, “has a straight stem.” Figure 14.3 shows that East Asians were inclined to think that the object was more similar to the group with which it shared a family resemblance, whereas European Americans were more likely to regard the object as similar to the group to which it could be assigned by application of the rule. Asian Americans, though closer to East Asians, showed no overall preference. (In several of our studies we have included Asian Americans. They were always intermediate in their responses and most typically closer to the European Americans than to the East Asians.)

Figure 14.1 “Which two go together?” Item from Chiu (1972) test.

Attention and perception differences

Differences between East Asians and Westerners extend beyond cognition to encompass many tasks that are attentional and perceptual in nature. Asians appear to attend more to the field and Westerners to attend more to salient objects.

Figure 14.2 “Which group does the target object belong to?” Target bears a strong family resemblance to group on the left but can be assigned to group on the right on the basis of a rule.

Figure 14.3 Percent of participants basing similarity judgments on family resemblance vs. rule.

Detection of covariation

If East Asians pay more attention to the field, we would expect them to be better at detecting relationships between events. Ji, Peng, and Nisbett (2000) presented arbitrary objects like those in Figure 14.4 to Chinese and American participants. One of the objects on the left appeared on the left side of a split computer screen followed rapidly by one of the objects on the right appearing on the right side of the screen. The participants’ task was to judge the strength of relationship between one object appearing on the left and a corresponding object appearing on the right. The actual strength ranged from zero – that is, the probability of a particular object on the right appearing was independent of which object appeared on the left – to a relationship equal in strength to a correlation of. 60. The Chinese participants saw more covariation than did American participants; they were more confident about their judgments; and their confidence was better correlated with the actual degree of covariation. At any rate, all of this was true in the setup just described. When some control over the setup was given to participants by giving them a choice as to which object to present on the left and how long an interval to have before presentation of the object on the right, American performance was entirely similar to Chinese performance.

Figure 14.4 Sample of arbitrary objects shown in covariation detection task.

Field dependence: Difficulty in separating an object from its surroundings

If East Asians are inclined to focus their attention simultaneously on the object and the field, then we might expect them to find it more difficult to make a separation between an object and the field in which it appears. Such a tendency is called “field dependence” (Witkin, Lewis, Hertzman, Machover, Meissner, & Karp, 1954). One of the ways of examining it is the Rod and Frame test shown in F...