![]() Stage II

Stage II

The dynamics of the relationship![]()

Chapter 4

Transference

The inarticulate speech of the heart

(Van Morrisson 1983)

We have proposed that the deconfusion stage starts with the development of the working alliance. In this chapter we seek to further an understanding of this phase of therapy by addressing the transferential relationship. The epigraph for this chapter is adapted from Van Morrisson’s (1983) album The Inarticulate Speech of the Heart. If you are familiar with Morrisson’s voice you won’t need any explanation. You don’t know why, but you feel moved; Van Morrisson transfers the inarticulate speech of his heart to us through his music.

How patients transfer the inarticulate speech of their injured or broken hearts to their therapists is the subject of the next four chapters. In the feminist Seventies there was a catch-phrase, immortalized on a badge that said ‘Is there life after marriage?’ One day, taking a train journey together, we (the authors) took the opportunity to discuss aspects of our book. We began to talk about transference and started to wonder not if there was ‘life after transference’ but if there was ‘life without transference’.

We came to the conclusion that to have a relationship with another person we have to transfer something of ourselves or our history onto the ‘other’, and that is often an unconscious process. Simply put, when we see someone smile we might ‘transfer’ trust without being particularly aware of this; or onto someone looking stern we might ‘transfer’ disapproval and so on. Would the ability to empathize with another’s experience be possible without this process? We think not. In the contrived and intimate atmosphere of the therapy room this process will be intensified because the feelings and experiences of the patient are the main focus of the relationship. This heightened self-consciousness makes transferring of unconscious aspects of self more possible. In a psychotherapy group with one black woman and seven white women, one of the white women, who had an upper-middle-class background, was assumed by the black woman to be racist, based upon her tone of voice and the professional status she held in society. What the black woman did not know was that the white woman had lived in Africa for many years, had black colleagues and friends, and was no more racist than anyone else in the group, including the therapist, and maybe even less so. However, the black woman had suffered considerable racism at the hands of the middle-class white establishment, as had her family, so she naturally transferred her introjected racist persecutors onto the person who most ‘fitted the bill’ in the therapy group. At the same time the white woman had often had to deal with the projection of superiority and oppressiveness not only from black people but also from working-class people. She was often the victim of other people’s assumptions about her class identity. She in turn could transfer onto those people, anticipating persecution and thinking of them as self-obsessed (which fitted with her experience of her narcissistic and rejecting mother).

It is obvious how this situation provided a rich potential for deepening awareness for both participants, and heightening racist awareness for the whole group. An analysis of these transferring experiences provided us all with the possibility to contain the inherent polarities of whiteness and blackness, of privilege and deprivation as we saw them unfold and change colour and meaning before our eyes. As we worked through the experiences of both women we, as a group, managed to hold out for the imaginative possibilities invoked by their transferences where neither woman’s experience was denied nor diminished. We stayed with our differences. Some wept for the irreconcilables we found therein; but no one left.

Rycroft (1968/1995: 168) describes transference as:

1. The process by which a patient displaces onto his analyst feelings, ideas, etc., which derive from previous figures in his life; by which he relates to the analyst as though he were some former object in his life, by which he projects onto his analyst object-representations acquired by earlier introjections; by which he endows the analyst with the significance of another, usually prior, object.

2. The state of mind produced by I in the patient.

3. Loosely, the patient’s emotional attitude towards his analyst.

This was the conclusion we arrived at on our train journey, except that we think of this as just ‘life’. Thus, for us, the transferential relationship is indistinguishable from any other relationship. It is part of how we cocreate the relationship between others and ourselves. In this view, it seems, we are in agreement with Freud (1925: 42), who wrote that transference ‘. . . is a universal phenomenon of the human mind . . . and in fact dominates the whole of each person’s relations to his human environment’. Moiso and Novellino (2000) argue that transactional analysts must not neutralize ‘the enormous methodological and clinical consequences of accepting and working with the transferential and countertransferential dimensions of transactions that occur within the psychotherapeutic relationship’ (p. 25). It is precisely for these reasons that we consider the transferential relationship to be central for transactional analysts when working with the deconfusion of the Child.

We now turn to those ‘enormous methodological and clinical consequences’ of working with the transference. We believe that it is important to define and identify transference, for we view this phenomenon as the vehicle by which the therapist will find out about the unconscious aspects of her patient, and indeed the patient about herself. In particular, we view this process as an attempt by the patient to communicate unarticulated experience of which she is unaware. When the verbal sense of self (Stern 1985) cannot find the language to describe inarticulate experiences, or when that verbal self has no knowledge and is cut-off from internal aspects of experiencing as described in our model of self (see Figure 2.4, page 25), then those aspects of self must make themselves known through a medium other than direct language. Often these other aspects of self are experienced as threatening to the patient’s cohesive sense of self (A0) but we have learned from Freud, and many since (and indeed from our own clinical observation), that what is repressed will come out in other ways. For instance we have observed that repressed experiences are revealed through the body, through behaviour, and through expectations, feelings and thoughts voiced in the presence of the therapist. How we understand and use this observation will, of course, be very different from Freud, and in particular the way we work with countertransference (see Chapter 5).

Feelings and emotions are central to an understanding of the non-verbal transferential relationship and are therefore an essential component of the therapy. ‘The neurological evidence simply suggests that selective absence of emotion is a problem. Well-targeted and well-deployed emotion seems to be a support system without which the edifice of reason cannot operate properly’ (Damasio 1999: 43). These findings seem to suggest that it is untenable to separate out feelings from emotions and, further, that feelings are linked inextricably to reasoning. It seems logical, then, to suggest that the emotional availability of the therapist is of paramount importance and, in this model, essential to an effective understanding of the transferential relationship.

The receptivity of the therapist to ‘catch’ the feelings and experiences is thus vital. Bollas talks about cultivating a freely aroused emotional sensibility, the analyst welcomes ‘news’ from within herself that is reported through her own intuitions, feelings, passing images, phantasies: ‘in order to find the patient we must look for him within ourselves’ (Bollas 1987: 202). In order to do this the therapist must allow the impact upon her ‘self’, once again revisiting those old areas of difficulty within. Bollas (1987) refers to the presence of two patients in the analytic encounter. From this we infer that it is the responsibility of the psychotherapist to acknowledge, recognize, and hear the drumbeat of her own inarticulate heart longings, in the service of understanding the communication from her patient.

It is difficult to write about transference as separate from countertransference because one cannot really exist without the other. In our view they are mutually interdependent and an absence of this understanding might explain why some therapies end abruptly. If a patient is unable to transfer the experience of her Child, then she might intuitively guess that there is nothing much in the therapy relationship for her and give up. Transference holds within it the potential for transformation because, if the therapist accepts it, she can use it to bring about change. We explore these ideas more fully when we talk about countertransference in Chapter 5. For the moment, we will attempt the very thing that we have called impossible and make a unilateral examination of the phenomena of transference.

Regression

At this point it seems timely to distinguish between working in the transference and the technique of ‘controlled regression’ often used in transactional analysis. Regressive techniques such as the two/three/five-chair work used in the redecision school, Pig Parent interviews, or contracting to regress to certain ages as in rechilding work, can sometimes be useful as decontamination techniques and as ways of offering new experiences to the client that sometimes effect change in the client’s intrapsychic system, perhaps by opening-up the possibility for new neural pathways. They also challenge script patterns in the adapted self (A1). However, the same techniques are not so helpful in deconfusion work because the processes of self-identity (A0) are not accessible to verbal structures and cannot be contrived. They need to emerge and evolve in the contained and holding relationship, as described in the self-object transferences (see Chapter 2). In addition, drawing upon the research into trauma by de Zulueta (2000), it would even seem potentially damaging for some patients to be encouraged to re-experience traumatic situations for the purpose of catharsis because the level of the chemical cortisol in the brain will already make them more vulnerable to retraumatization. Could regressive techniques and cathartic work become addictive and provide continuing opportunities for retraumatization or the establishment of ‘new’ defensive patterns? For example, a client who had considerable trauma in her childhood began to train as a psychotherapist. She took the opportunity to join several therapy intensives, and eventually seemed to belong to a variety of different groups. Her therapist heard, with alarm, of her experiences, which sounded like enactments of the original injuries. The therapist noted that the client often described what sounded like manic experiences, full of cathartic affect, yet leaving the client unchanged in a fundamental sense of the word.

These types of regression are quite different from the spontaneous internal regression that might occur, for example, from just being in the room with an attentive other person. For instance, Beatrice, in Chapter 1, found it so threatening that she tried to leave half way through the first session. It is easy to misread a client and not recognize, from the self-image presented, how regressed they are internally, as was the case with Beatrice.

Empathy and transference

Some will argue that the therapist’s emotional responsiveness is more accurately defined as empathy rather than countertransference (Reich 1966). But we think this view underestimates the wealth of emotional knowledge available through the transference and would effectively neutralize the potential for bringing the unconscious into the here and now reality. Overall, we view the transferential process as an attempt, by the patient, to use the therapist to change something that cannot be changed by cognitive/behavioural means alone. An example of precisely this therapeutic need is Alan, a man who had suffered gross abuse, neglect and tragic abandonment in his childhood. Alan presented for psychotherapy having already spent many years in psychiatric care, and being in and out of therapy experiences. Despite all the treatment, something inside refused to budge and he knew that he needed to be with a therapist who was able and willing to ‘take on’ the transference. A particularly bright individual, Alan articulated this requirement of his therapist in his first session and he was honest enough to admit that several therapists had refused to work with him because of the nature of his abusive background. The therapist did not accept him lightly because she knew she would be required to take on ‘roles’, deal with projections and experience some dreadful feelings. He intuitively knew that he was asking a lot and, indeed, the therapist only discovered exactly how much as she allowed herself to be impacted emotionally by this man. In our view this patient required someone who was willing to ‘offer’ his or her own ‘self’ for the possibility to transform his experience. In our relational model we refer to this process as the use of the therapist’s ‘self’ as a vehicle for change.

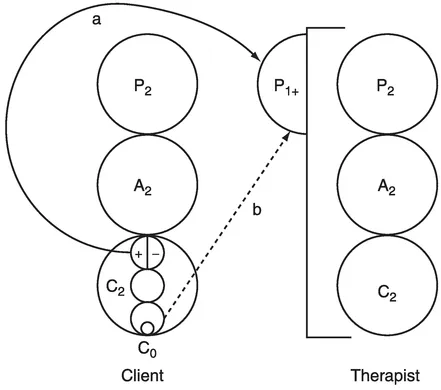

We have found it useful to draw upon some of the ideas from self psychology when considering the transferential domain. For instance, Kohut’s (1971) description of the self-object transferences seems to be consistent with the longings that emerge from the infant’s needs and requirements of the environment. The developmental history of the client will inform the type of transference that becomes foreground in the relationship. We develop Moiso’s (1985) transference model, to distinguish between the three different types of transference (Figure 4.1) as follows:

- introjective transference/C0 longings

- projective transference (P1+/P1−)/defensive and splitting transferences

- transformational transference (C1/P0)/primitive affect.

Figure 4.1 Projective and introjective transferences (based on Moiso 1985).

These categories are meant as a map to enable the therapist to chart some of the complex feelings that emerge through the transference. These transferential domains are not really discrete and coexist alongside each other in the treatment. Overall, we consider all types of transference as a call from the patient for the therapist to find the appropriate emotional response. A theoretical distinction between transferential phenomena can be supportive to the therapist because the intensity and type of transference will be the result of the patient’s experience of self. The more insecure and ruptured the earlier attachments were, the more fragile the sense of self will be and some patients will implicate the therapist in a multi-transferential relationship.

For example, the extent of unmet need in the client’s Child (C0) will involve psychological strivings for mirroring, idealization and twinning referred to as the self-object transferences (Kohut 1971) which, drawing on the work of Menaker (1995), we put under the category of the introjective transferences. The projective transferences are really more concerned with the maintenance of script, the confirmation of A1+ or A1− constructions of self and the splitting between good and bad object representations. This transference emerges most strongly with those patients who have had very insecure attachments and is most commonly understood in patients showing borderline features. Closely linked to this is projective identification, which is a more intense type of transference particularly needed by patients where there has been significant fragmentation in the early development of the child ego (C0). Initially developed by Klein (1975/1988), we draw upon the work of Ogden (1982/1992) to discuss this transference. Ogden particularly captures the sense of pressure, which comes from the patient to the therapist in an attempt to induce, control and make the therapist do something. We amplify upon this further under the headings below.

In the following discussion we expand upon each type of transference using vignettes to support our meaning. Inevitably, the transferences overlap with each other and the vignettes are not ‘pure’ examples of the type of transference. For instance, we consider that aspects of P1 are involved in both the projective and transformational transference. The P1 projection either can be the projecting of unmanageable object relations, as in the projective transference, or it can occur when the therapist is very engaged with the client and finds that she is holding the P1 component of the self at an affect level, for example, in the form of rage or destructiveness. Nevertheless, we think the categories contain enough of an individual flavour to be of clinical assistance when working through the maze that can be the transferential relationship.

Introjective transference

Introjection is both a defence and a normal developmental process; a defence because it diminishes separation anxiety, a developmental process because it renders the subject increasingly autonomous

(Rycroft 1968/1995)

In this type of transference the patient seeks to enter a symbiosis (Schiffet al. 1975) with the therapist in order to meet developmental needs (C0). In this transference the patient seeks to introject the therapist as an unconscious psychological striving towards health and autonomy.

As outlined in Chapter 1, the developing child (C0) needs a good enough other/others (P0) who is/are sufficiently attuned to his needs so that he c...