1

Cognitive Vulnerability to Emotional Disorders: Theory and Research Design/Methodology

John H. Riskind

George Mason University

Lauren B. Alloy

Temple University

Emotional disorders have adversely affected human lives since the earliest recorded history. As long ago as 400 BC, Hippocrates identified “melancholia” and “mania.” Today, emotional disorders rank at the top of any list of the most devastating mental illnesses in Western society (e.g., Rovner, 1993). As many as 46 million individuals in the United States alone suffer from depression and anxiety disorders (Kessler et al., 1994). The enormous impact on society (e.g., health costs and disability, job loss, health problems) has prompted a great deal of effort to search for their causes. This quest has been inspired by a variety of conceptual paradigms—psychoanalytic (Freud, 1964), biological (Meehl, 1962), attachment (Ainsworth, 1982; Bowlby, 1969), environmental life stress (Monroe & Simons, 1991), and learning approaches (Lewinsohn, 1974; Mowrer, 1939).

The cognitive revolution of the 1950s and 1960s became a formidable force in psychology. One of its results was the introduction of a cognitive paradigm for understanding the causes of emotional disorders. Cognitive theorists maintained that cognition, or more specifically, maladaptive cognition, plays a central role in the etiology of emotional disorders (e.g., Beck, 1967; Kelly, 1955; Seligman, 1975). The emergence of cognitive perspectives, and their forerunners (e.g., Ellis, 1970; Kelly, 1955; Rotter, 1954), represented a dramatic shift from other conceptual paradigms in the conceptualization and treatment of emotional disorders. As a good illustration, consider the radical changes that swept the depression literature in the late 1960s. Shattering the traditional assumption that depression was simply affective and biological, Beck’s cognitive model was based on the idea that systematic cognitive distortions in thinking about the self, world, and future help to catalyze and maintain depression and other emotional disorders. Seligman’s (e.g., 1975) work on the phenomenon of learned helplessness eventually led to ways to fuse Beck’s cognitive clinical observations with an experimental tradition in studying depression (e.g., Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978). During the past three decades, experimental cognitive traditions that deal with attention, memory, and information processing have been extended to depression, anxiety, and other disorders (e.g., Mathews & MacLeod, 1994; J. M. G. Williams, Watts, MacLeod, & Mathews, 1988).

This chapter reviews some of the basic issues relating to theory and to the design and methods of cognitive vulnerability research on emotional disorders. It first discusses basic tenets of cognitive models of emotional disorder, including the concept of cognitive mediation and vulnerability–stress interaction, and common features of a prototypical cognitive vulnerability model. It also examines important issues that remain for further investigation (e.g., comorbidity, developmental pathways, the interaction of cognitive and biological vulnerabilities). It then describes issues concerned with the interface of theory and research design, including the crucial role of theory in determining the proper design of research studies. Actual design options and methods used in cognitive vulnerability research, and their strengths and limitations, are also discussed. Finally, there is a brief summary and concluding comments.

BASIC TENETS OF COGNITIVE MODELS OF EMOTIONAL DISORDER

The most basic tenet of cognitive clinical models is that cognitions mediate the relation between events that people experience and the emotions that they feel. A passage from Dickens aptly illustrates this keystone of cognitive models of emotional disorders and other psychopathology. It clearly conveys the fact that individuals can radically differ from each other in the ways that they privately explain and understand different characteristics of the same stimulus event:

“Oh, you cruel, cruel boy, to say I am a disagreeable wife!,” cried Dora. “Now, my dear Dora, you must know that I never said that!” “You said I wasn’t comfortable!” said Dora. “I said the housekeeping was not comfortable!” “It’s exactly the same thing!” cried Dora. And she evidently thought so, for she wept most grievously. (Dickens, 1979, p. 616)

The basic precept of cognitive models of emotional disorder, then, is that a person’s emotional responses to a situation are influenced by the interpretation (or appraisal) the person makes of its meaning (e.g., Fridja, 1987; Lazarus, 1991; Ortony, Clore, & Collins, 1988; Roseman, Spindel, & Jose, 1990). People’s appraisals are not simple mirrorlike reflections of the elements of objective reality. Hence, it is not only a particular situation that determines the way people feel or emotionally respond, but also the special meaning that is subjectively constructed by the person that is important. It is just as important that the situation (absolute reality) does not directly determine how the person feels or responds. The same guiding principle applies to stimuli that are perceived within the interior of the person (e.g., physical sensations, thoughts, emotions) as to stimuli that are found in the external environment.

Cognitive models are also based on the general idea that there is a continuity of normal and abnormal cognitive processes. For instance, Beck (1991) stated that “the [cognitive] model of psychopathology proposes that the excessive dysfunctional behavior and distressing emotions or inappropriate affect found in various psychiatric disorders are exaggerations of normal adaptive processes” (p. 370). Thus, it is quite simple to apply the presuppositions of cognitive models to emotional disorders such as depression and panic disorder, or related ones such as eating disorders. For example, triggering events such as a social rejection or a small increase in body weight are construed by some individuals as a small setback; others perceive them as no less than decisive evidence of utter failure and personal defect. In addition, some people exhibit relatively characteristic or stable patterns in the ways in which they appraise emotion-provoking stimuli (e.g., Abramson et al., 1978; Riskind, Williams, Gessner, Chrosniak, & Cortina, 2000; Weiner, 1985). The bottom line is that habitual differences in the manner in which people interpret particular kinds of events can affect their future risk for developing particular kinds of emotional disorders.

The cognitive factors conceived to be important in emotional disorders can include both distal phenomena that were present before the disorder, and proximal phenomena that occur very close to, or even during, the episode of disorder and its symptoms (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989). Distal cognitive factors are normally relatively enduring cognitive predispositions to respond to stressful situations in maladaptive ways (e.g., dysfunctional attitudes or explanatory styles). They are higher in generality (or abstraction) as well as more distal to future episodes of disorders than proximal cognitions, which are more transitory or specific thoughts or mental processes that occur very close to, or even during, the episode of disorder. And, proximal cognitions (e.g., specific thoughts or images) are typically produced when individuals process the meaning of a stressful event in any situation through the filter of the underlying cognitive vulnerability.

Cognitive Vulnerability–Stress Paradigm

Today, most cognitive models presuppose that the outcomes resulting from cognitive vulnerabilities depend on interactions with environmental precipitants. Some good examples of precipitants include stressful life events, early childhood traumas, faulty parenting, or medical injuries. In other words, the models incorporate a vulnerability–stress paradigm in which it is recognized that psychological disorders are caused by an interaction between predisposing (constitutional or learned) and precipitating (environmental) factors. These factors can trigger the development of emotional disorders or psychological problems for certain individuals (e.g., see Alloy, Abramson, Raniere, & Dyller, 1999), but the specific degree and even direction of the response can differ enormously from one person to another. For example, some individuals seem to be relatively “resilient” and often overcome the difficulties that accompany stressful events (e.g., Hammen, 2003); others seem overwhelmed by even minor problems. Thus, precipitating events are particularly likely to produce emotional disorders among individuals who have a preexisting cognitive vulnerability to the disorders.

Most individuals in stressful situations do not develop clinically significant disorders. Moreover, the specific disorder that emerges for different individuals is not determined just by the precipitating stress alone (i.e., precipitating stresses do not just occur in conjunction with any one clinical disorder). For example, stressful events are elevated in depression (Brown & Harris, 1978; Paykel, 1982), bipolar disorder and mania (see chap. 4, this vol.; Johnson & Roberts, 1995), anxiety disorders (Last, Barlow, & O’Brien, 1984; Roy-Byrne, Geraci, & Uhde, 1986), and even schizophrenia (Zuckerman, 1999). In light of these findings, cognitive vulnerability–stress models are offered to help account for not only who is vulnerable to developing emotional disorder (e.g., individuals with a particular cognitive style), and when (e.g., after a stress), but to which disorders they are vulnerable (e.g., depression, eating disorder, etc.).

The earliest vulnerability–stress models (e.g., Meehl, 1962) emphasized constitutional biological traits (e.g., genetic traits) as vulnerabilities. But, this approach was quickly expanded in terms of cognitive vulnerabilities, personality factors, and interpersonal strategies (e.g., Abramson et al., 1989; Blatt & Zuroff, 1992; D. A. Clark, Beck, & Alford, 1999; Ingram, Miranda, & Segal, 2001; Joiner, Alfano, & Metalsky, 1992; Rachman, 1997; Riskind, 1997; Robins, 1990). Researchers in the cognitive tradition favor the term vulnerability to diathesis, because the former term embraces the idea of learned and modifiable predispositions, instead of immutable genetic or biological traits (e.g., Just, Abramson, & Alloy, 2001).

Beck’s (1967, 1976) theory was the earliest to expound a cognitive vulnerability–stress interaction. Beck postulated that whether or not individuals possess an enduring cognitive predisposition to emotional disorders depends on if they have acquired maladaptive knowledge structures or schemata during the course of childhood. These schemata are internal frameworks, constructed of attitudes, beliefs, and concepts that individuals use when they interpret past, present, and future experiences. Because they influence the ways in which they interpret and initially experience events, schemata moderate the idiosyncratic subjective meaning and thus the impact of stressful events. These cognitive schemata promote maladjustment when they are poorly grounded in social reality or are otherwise dysfunctional. Hence, individuals with maladaptive schemata are more likely to make dysfunctional interpretations of stressful events that increase vulnerability to emotional disorders. Once they have made such appraisals (e.g., of failures as personal defects), a series of changes in mental processes are initiated that can culminate—by way of changes in the contents of thinking and information processing—in depression or anxiety. Thus, in Beck’s cognitive model, emotional disorders result from a combination of predisposing, environmental, and developmental factors that lead individuals to engage in dysfunctional thinking and information processing.

COMMON FEATURES OF COGNITIVE VULNERABILITY MODELS: A FRAMEWORK ENCAPSULATING RELATIONSHIPS

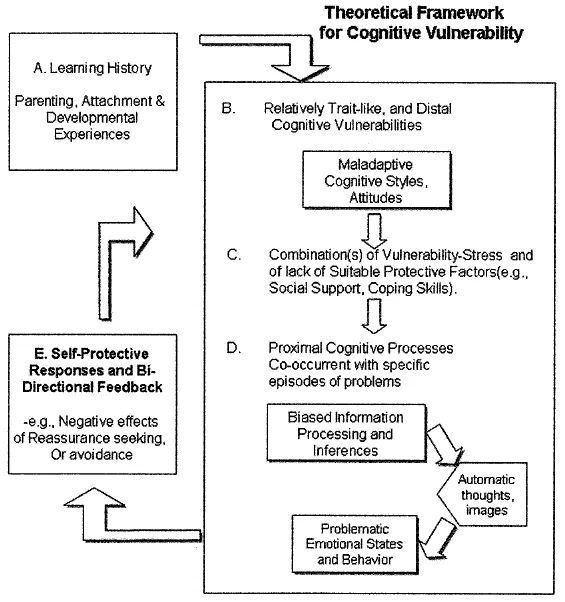

The conceptual framework presented in Fig. 1.1 depicts several distinct features of the prototypical cognitive vulnerability model of emotional disorders and other psychological problems. Such cognitive models generally share the assumption that there are a series of causal chains by which enduring vulnerabilities develop and (with relevant stressor combinations) become converted into the emotional disorders or problems. These causal chains commence with earlier life experiences (e.g., faulty attachment relationships, childhood traumas, modeling) that lead individuals by means of developmental pathways to develop cognitive vulnerabilities. Once cognitive vulnerability factors have coalesced and are put into play or are activated, they alter the individual’s responses and are seen as serving schematic processing functions (e.g., D. A. Clark, Beck, & Alford, 1999). That is, the cognitive vulnerabilities represent a mental mechanism that shapes the individual’s selective processing, attention, and memory, and molds changes in the concomitant contents of the individual’s thinking (i.e., the ideation, imagery, or “automatic” thoughts”).

FIG. 1.1. Theoretical framework for cognitive vulnerability.

Although a vulnerability–stress interaction is a central feature of cognitive vulnerability models, there are many possible variations. First, the triggering conditions that are hypothesized to precipitate symptoms or episodes of disorder may be both “public” and “private” events. Public events include achievement failures, disruptions of interpersonal relationships, or collectively evident threats to well-being. Private events include unusual bodily sensations, unwanted thoughts, or traumatic memories. Thus, the putative cognitive vulnerability that influences the risk of emotional disorder can be represented by a depressive inferential style (see chap. 2, this vol.), a cognitive network of negative self-referent cognition (chap. 3, this vol.), a looming cognitive style (chap. 7, this vol.), or a tendency to catastrophically misinterpret the meaning of experienced bodily sensations (see chap. 8, this vol.). In this conceptual framework, the output is represented by the emotional disorder or symptoms that result from the interaction between the precipitating event and cognitive vulnerability.

A critical element of many cognitive models is that specific biases of information processing and proximal cognitions are assumed to differ with different disorders (Beck & D. A. Clark, 1997; J. M. G. Williams et al., 1988). For example, the bias in social phobia is for information relevant to the threat of public humiliation, and is accompanied by proximal thoughts like “I’ll make a fool of myself” (see chap. 10, this vol.). The specific bias in panic disorder is for information relevant to unusual bodily sensations that might signal impending heart attacks or other feared calamities, and is accompanied by thoughts such as “I’m having a heart attack” (see chap. 8, this vol.). Such “disorder-specific” informationprocessing biases are presumably instigated when cognitive vulnerabilities (the distal factors) are put into play or engaged that were present long before the symptoms or episode. Hence, the specific vulnerability hypothesis of cognitive models is that the vulnerabilities to different disorders can dramatically differ. The mental processing biases can in...