What is Hybrid Animation?

Hybrid animation is the combination of 2D and 3D animation mediums. 2D and 3D animation mediums can be used, and are used, independently of one another. Pixar’s B.O.O.: Bureau of Other worldly Operations or Inside Out are completely 3D animated films. Disney’s Little Mermaid and Miyazaki’s (Studio Ghibli) The Wind Rises are completely 2D animated films.

Yet, ever since the first appearance of a 3D glowing bauble in a 2D animated film, Disney’s The Black Cauldron, artists have been finding inventive ways to combine the animation mediums. The use of 2D/3D at Disney predates The Black Cauldron and can be seen in a short test done by John Lassiter titled Where the Wild Things Are (1983). In Japanese animation, 2D/3D can be seen as early as Princess Mononoke (1997) and Ghost in the Shell (1995) and as recently as Berserk Golden Age Arc 3 Descent (2013).

FIGURE 1.2 The bauble from Disney’s The Black Cauldron (1985) was one of the first 3D elements to be combined with 2D animation

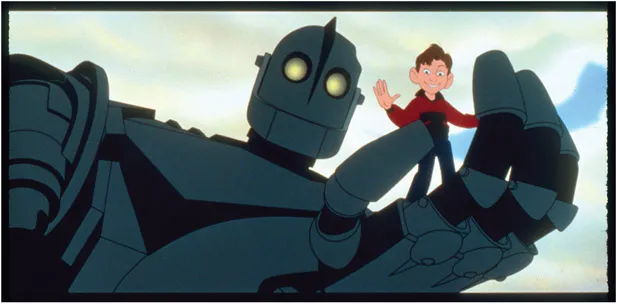

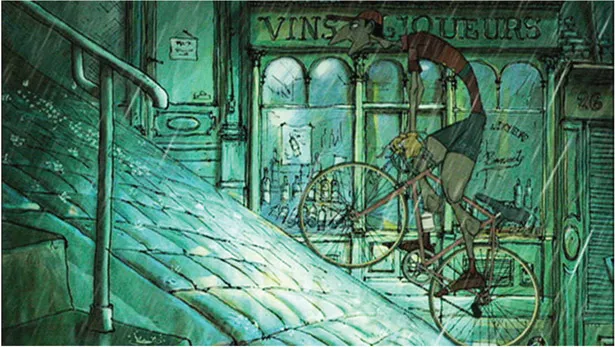

What combinations of 2D and 3D are there? Rendering characters in different mediums is the first type of combination. Some of the earliest examples can be found in the Academy Award– nominated short Technological Threat (1998) and also in a wonderful short film produced at Disney’s Florida Studio called Off His Rockers (1992). In feature animated films, probably one of the most memorable combinations of mediums is found in Warner Bros.’ The Iron Giant (1999), in which a young boy befriends an alien robot; the robot being 3D in a 2D animated film. However, characters themselves do not need to be completely rendered in one medium or another, as was the case with the character John Silver in Disney’s Treasure Planet (2002), or the bicyclists in The Triplets of Belleville (2003). In those films 2D characters were drawn with 3D appendages rendered to match the 2D portions. Most recently, the overall characters themselves can be a combination entirely of 3D and 2D as was seen in Disney’s Oscar-winning short Paperman (2012), where the animation was created in 3D and then 2D animation was done overtop of the 3D. Lastly, the most common use of combining mediums is for non-character animation elements. This combination of 3D elements into 2D animation is seen in almost any modern 2D animation: Mulan, The Simpsons, Family Guy, and Futurama, to name a few.

FIGURE 1.3 2D character with 3D parts riding a 3D bike found in The Triplets of Belleville

Now, let’s clarify exactly what 2D and 3D animation assets are and how they are created, just to make sure we are all clear. You might be proficient with a few of these creation methods. During the course of this book, hopefully, you will find yourself experimenting with other methods. A large, looming goal of this book is to show you the path to fearlessness and flexibility with software, because at the end of the day, it is animation—that’s all.

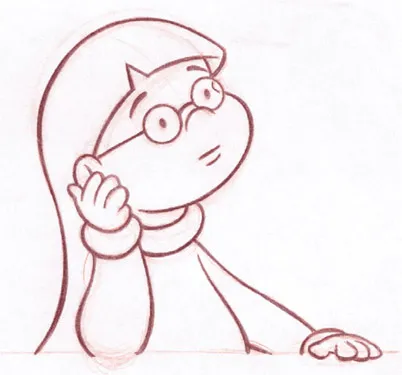

2D animation assets are images that exist only in two dimensions during creation; a very academic definition. How the 2D images are created is the interesting part that must be dealt with in your pipeline. These images can be created in the birth tradition of animation using pencil and paper and then scanned into a computer for compositing. Traditional animation artists have had great success in drawing their images digitally using software such as Photoshop, Flash, or Toon Boom, to name a few. Other ways of creating 2D animation images include painting on glass, drawing in sand, scratching on film, or other flat methods of creation. All of these methods fall under the 2D animation category.

FIGURE 1.4 2D traditional character “M.E.,” animation (red) by Tina O’Hailey, cleanup (graphite) by John O’Hailey

FIGURE 1.5 Image from “How to Throw a Jellyfish Party” drawn and animated in Flash by Dan Murdock, 2008, Digital Cel I Course, SCAD

3D animation assets exist in three dimensions during the creation process. More academic-speak, but look at the key phrase: “during the creation process.” Live-action film would come under this category if we were not limiting ourselves to animation assets. 3D animation assets include digital and stop-motion animation. Digital animation can be created in 3D software packages such as XSI, Maya, Max, or a multitude of other lower-budget software such as Blender, Wings, and the like. Stop-motion is the process of animating tangible items in front of a camera, usually poseable puppets made of clay, silicon, or other materials. There is a sub-category of stop-motion called pixilation, which uses live objects, recorded frame by frame, to create an animation.

FIGURE 1.6 3D character modeled by Erik Minkin, 2014, SCAD

FIGURE 1.7 Character from stop-motion animation “King Russ” by M. T. Maloney

Since we are focusing on animation and not live action, combining film or video with 2D or 3D animation is beyond the scope of this book. However, the same problem-solving concepts and compositing techniques covered in this book can be applied toward combining live action and animation.

Why Use One Medium Over the Other?

Artists’ imaginations continue to grow and stretch the boundaries of animation to tell stories. It can become difficult to decide which medium is best to tell the story. Sometimes, fad decisions are made based on the newness of a medium.

To take an objective look at the decision, these following five reasons show why one medium might be preferred over another:

- Visual target not subject matter

- Line mileage

- Complexity

- Team skills versus production schedule

- Physical assets and budget

Visual Target Not Subject Matter. The visual target or visual style of a film is a large factor in deciding which type of medium will be chosen. It is no longer the subject matter that is the deciding factor. The division between what medium is best for what subject matter has become so blurred as to be nonexistent. 3D software techniques have advanced so that humans, furry animals, and other warm-looking creatures are no longer out of their grasp. Which medium lends itself best to the artists’ final vision is the question to ask. This will be answered with strong art direction and experimenting during pre-production.

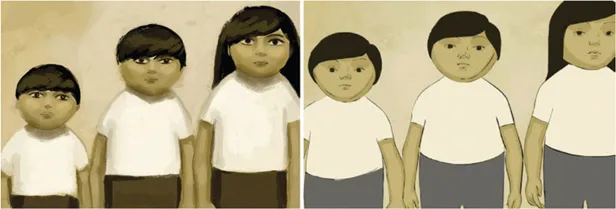

FIGURE 1.8 Visual style and frame of final 2D/3D animation by Claire Almon, 2007, SCAD

Line Mileage. “Line mileage” is a term meaning how much line you have to physically draw. If you were to take a traditional drawing and stretch out the lines end to end you would see what your “line mileage” is. Every millimeter more of pencil or digital line takes more time to draw. Intricate character designs may look good as still images, but the reality of animating such a character is time consuming. A character with long, curly hair, wearing a wrinkly overcoat, multiple ammo straps over his shoulders, and a striped shirt has extra line mileage. It is difficult to keep so many lines moving well without seeming to crawl, pop, or distract from the animation.

FIGURE 1.9 Line mileage is how much line must be drawn, shown here by stretching out the drawing end to end

If a traditional medium is chosen and the animation is fully animated, line mileage is looked at very closely and characters are simplified in order to minimize the line mileage. An example: on a fully animated film, such as Disney’s Lilo & Stitch, the character Nani’s t-shirt had on its front a coffee cup design. The design was simplified to a heart in order to lower the line mileage. This may not seem like a large simplification. Given that Nani was in so much of the movie, the seemingly small simplification along with many others added up to less time spent drawing. Anime characters can be designed with more detail since the animation style dictates minimal inbetweening of the characters.

A common multiplier of line mileage is crowds. If a traditional animated film calls for crowds of people, that is a ton of line mileage. In order to simplify the line mileage, many 3D crowd techniques have been used. 3D crowds were rendered to match the 2D line style in Disney’s Hunchback of Notre Dame and with the Hun charge in Mulan. Another method used is to procedurally populate a 3D wo...