![]() Cataloging Audiovisual Formats

Cataloging Audiovisual Formats![]()

Cataloging Popular Music Recordings

Terry Simpkins

SUMMARY. This paper provides an overview of the cataloging process for popular music sound recordings, from the initial description of the item to the final assignment of subject headings and name and/or title access points. While isolated aspects of the process have been covered in general elsewhere, little has been written describing the entire process especially as applied to popular music recording cataloging specifically. The paper also briefly discusses useful reference sources for popular music cataloging and problems of indexing and keyword searching as they relate to popular music recordings.

[Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-342-9678. E-mail address: <[email protected]> Website: <http://www.HawonhPress.com> ©

2001 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.] KEYWORDS. Sound recordings, popular music, cataloging, keyword searching, subject cataloging, descriptive cataloging, music cataloging, compact discs, jazz

Introduction

Cataloging recordings of popular music1 presents challenges to both experienced music catalogers and novices alike. While many aspects of cataloging popular music recordings are identical to cataloging recordings of Western art music,2 certain problems seem to arise more frequently with popular music material. The dizzying speed with which the music industry releases new recordings, the lag time between new styles of music and the creation of Library of Congress (LC) subject headings to cover them, the frequent mixture of format types-is it a sound recording or a computer program?-and the global "cross-pollination" of music styles are just a few of the problems popular music catalogers encounter every day. This article aims to examine these problems and offer practical strategies for coping with them. In order to present this information in as orderly a fashion as possible, this discussion mirrors the arrangement of topics in Anglo-American Cataloging Rules, 2nd edition, 1998 revision (AACR2).3 It begins with an overview of the descriptive cataloging process and then examines issues related to the formulation of main and added entries. The article closes with a discussion of subject cataloging issues.

Like every other type of cataloging, cataloging popular music recordings requires a few essential tools. These include AACR2, Library of Congress Rule Interpretations (LCRI),4 LC Music Cataloging Decisions (MCD),5 Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH),6 and documentation explaining the MARC bibliographic format (MARC21) such as MARC 21 Format for Bibliographic Data7 or OCLC's Bibliographic Formats and Standards.8 Jay Weitz's Music Coding and Tagging is also useful for cataloging music materials using the MARC format, although it is now seriously outdated.9

The cataloging process usually begins with a technical reading of the item aimed at determining the chief source of information according to AACR2 rules 6.0B 1. It moves through the transcription and descriptive processes, and then shifts to the assignment of access points and subject headings. Some libraries then classify their recordings using the LC classification schedules or some other scheme, but most libraries dispense with this in favor of simply assigning the item an accession number; this paper does not discuss classification issues relating to sound recordings.

Problems of Description

Richard Smiraglia has covered the descriptive portion of sound recording cataloging in detail.10 His books cannot be recommended highly enough to all music catalogers, regardless of one's level of experience, for an overview of this portion of the cataloging process. Suzanne Mudge and D. J. Hoek have also written a useful article aimed specifically at describing jazz, blues, and popular 78-rpm records.11 I will concentrate here on points of particular relevance to popular music catalogers working with contemporary recording formats.

Title

According to AACR2 6.0B1, the chief source of information for a sound recording is usually the item itself (the disc, cassette, LP, etc.) and any attached label(s). This raises two potential difficulties. For older formats such as cassettes, LPs, or 45-rpm singles where there are labels on both sides of the disc or cassette, both labels are considered to be part of the chief source. If the item lacks a collective title, rule 6.1G1 provides two methods for describing the item: as a single unit (i.e., transcribing data from both labels) or by making a separate bibliographic description for each separately titled work on the recording. The former approach is the one currently used by the Library of Congress (LCRI 6.1G1). The latter approach was standard practice prior to the adoption of AACR2; if this method is used, rule 6.1G4 provides guidance for formulating the physical description area and for the creation of "With" notes.

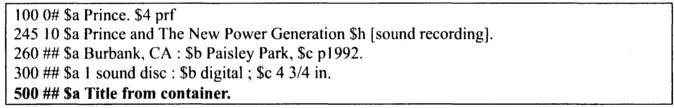

Another problem is that many recording companies treat the disc label as more of a decorative area than an informational one. In this situation, 6.0B1 instructs us to take information from the accompanying textual material, the container, or other sources, in that order. A complementary rule, 6.7B3, tells us to indicate the source of the title proper in a note if it comes from somewhere other than the chief source. Compact discs and cassettes can cause confusion here due to the presence of a plastic container through which the accompanying insert is visible. If the title is taken from the front of this insert (visible through the closed container), MCD 6.0B 1 tells us to treat this as if it were part of the container, and we should formulate our note accordingly (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Bibliographic record for compact disc with no information on the label. Note: the bibliographic records shown in this and the following examples are incomplete; only the portions relevant to the topic under discussion and the MARC21 fields 100, 245, 260, and 300 are shown.

General Material Designation (GMD)

The general material designation (GMD) normally presents few problems. Although rule 6.1C1 presents this as an optional addition to the title area, most libraries follow the related LCRI and routinely include the GMD "sound recording." The GMD (MARC21 245 $h) immediately follows the title proper (MARC21 245 $a and, if present, $n and $p). This means that, for an item lacking a collective title, the GMD follows the first title, excluding subtitles, other title information, etc. The GMD should always be enclosed in square brackets.12

Statement of Responsibility

The statement of responsibility area is covered by AACR2 rule 6.1F1. Here for the first time in AACR2 chapter 6 we encounter the division between popular and art music. Rule 6.1F1 states:

If the participation of the person(s) or body (bodies) named in a statement found in the chief source of information goes beyond that of performance, execution, or interpretation of a work (as is commonly the case with "popular," rock, and jazz music), give such a statement as a statement of responsibility. If, however, the participation is confined to performance, execution, or interpretation (as is commonly the case with "serious" or classical music and recorded speech), give the statement in the note area.13

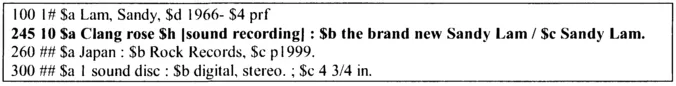

In other words, performers of popular music are presumed to bear more intellectual responsibility for their works than performers of art music. (As we will see, this difference in treatment is also apparent in LCRI 21.7B, which instructs catalogers not to provide name-title analytics for the contents of popular music sound recordings.) If, then, the performer's name is present in the chief source of information, generally transcribe it in the statement of responsibility area (MARC21 245 $c). If the name appears as part of the title, rule 1.1F13 instructs us to transcribe it in the statement of responsibility area only if it is required for clarity or if the name also appears separately in the chief source of information (Figure 2).

Rule 6.1F1 also allows catalogers to include in the statement of responsibility producers who have some form of artistic or intellectual responsibility for a recording, so long as they are named prominently in the item (i.e., in the chief source). Although producers often do have considerable artistic responsibility for popular recordings, they are rarely named prominently in the item and rarely transcribed in the statement of responsibility area.

Publication Information

The most problematic aspects of the publication area for popular music recordings are determining the name of the publisher and the date of publication. According to AACR2 rule 6.4D2, if there is both a publisher's name and a trade name on a recording, the trade name should be used in the publisher's name area (MARC21 260 $b). Smiraglia makes the useful observation that the trade name usually appears in conjunction with the manufacturer's number,14 and, according to rule 6.0B2, this information can be taken from virtually anywhere on the entire item. In practical terms, this means to record the name of the record label on the item (i.e., the name that users would most likely be familiar with), not the name of the parent company (which is often found in the fine print on the bottom of the container verso). For example, if the name "Columbia/Legacy" appears on the label and container spine

FIGURE 2. Performer's name appearing in the chief source of information both as part of the title and separately, as a statement of responsibility. Both occurrences are transcribed in the 245 field.

while "Sony Music Entertainment"-the parent company-appears in fine print on the CD container, then "Columbia/Legacy" would be transcribed as the publisher name. Finally, LCRI 6.4D1 also tells us to apply the optional provision in AACR2 rule 6.4D1 and to include the name of the distributor, if one is present, in the publication area.

Assigning a publication date can be tricky because of the frequency with which popular music is repackaged and recycled. For example, a work may be plucked from its original source (whether an album, single, or unreleased alternate take gathering dust somewhere inside a record company's archives) and then repackaged as part of a "greatest h...