![]()

1

Nature Unbound

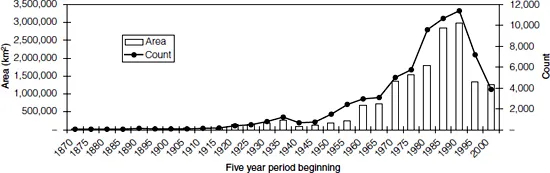

A good place to begin a study of wildlife and landscape conservation is to look at trends in the growth of protected areas in the last few years. Protected areas are all the national parks, game reserves, national monuments, forest reserves and the myriad other places and spaces for which states provide special protection from human interference. There is a curious pattern in their recent history, which we have shown in Figure 1.1. The period of most dramatic growth was between 1985 and 1995. While these data have to be treated with caution, the pattern is striking and its timing odd.1 For that time was also the period when neoliberal economic policies were dominant globally (Peet and Watts, 1996). Neoliberalism is based on the ideas of reducing the power, reach and interference of government (expressed in the catchphrase ‘small government’) and giving industry greater freedom and less red tape. Neoliberal policies were favoured by the powerful financial institutions, particularly the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, with tremendous influence over the details of many governments′ policies through the implementation of economic liberalization in the form of Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs) (Clapham, 1996; Harrison, 2004, 2005). Yet it was precisely when pressures to reduce government were greatest that the extent of state control and restriction on land and natural resource use increased more dramatically than any other period.

Could there be a mechanism behind the pattern, or is it mere coincidence? Could there be anything about the nature of modern capitalism that seems to favour the establishment of protected areas? One explanation is that conservationists have collectively responded to the threats and damage of contemporary capitalism by securing lands from development. In the face of increased development pressures they have risen to the challenge, identifying the places that need protection, fighting and winning the political battles required for governments to support their plans. They have created international conventions to further their cause, strengthened conservation and wildlife departments in numerous countries to fight for nature, as well as nurturing and training state actors throughout the world to champion conservation causes in their respective countries (Frank et al, 2000).

There is some truth to this idea, many protected areas were set up explicitly to limit development and had significant success in doing so. Fights to save places such as Jervis Bay near Sydney in Australia, and the West Coast Forests in South Island, New Zealand, resulted in new, or stronger, protected areas. Moreover these fights have been defining moments in the history of environmentalism. The successful campaigns to prevent the construction of the Franklin Dam in Tasmania, and the dams proposed in the Dinosaur National Monument in the US, strengthened and invigorated the movement internationally. Conversely, in India for example, extractive and timber corporations find that protected areas limit their operations and have actively campaigned for their denotification (Saberwal et al, 2001).

Figure 1.1 The global growth of protected areas

Source: The World Database of Protected Areas (2005);

Many contemporary battles are also fought on these lines, while expanding to include the question of indigenous land rights. For example current disputes about oil exploration in Alaska and its impact on the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) represent a complex mix of national security, indigenous rights, notions of wilderness and global energy supply (Lovecraft, 2007). The ANWR was established in 1960 to conserve wildlife populations in their natural habitats.2 Supporters of opening ANWR for oil exploration have claimed that it could reduce dependence on oil supplies from the Middle East and that current oil installations in ANWR have been designed and sited to take account of wildlife populations. Critics are adamant that the area should remain as a ‘pristine wilderness’, while other interest groups have lobbied for the rights of indigenous groups to maintain their access to fishing grounds.3 The creation of the Kuna Yala Reserve in Panama united conservationists and indigenous peoples in the protection of indigenous homelands from the environmentally destructive spread of homesteaders and cattle ranchers (Chapin, 2000). Alliances between the Kayapo Indians and international conservationists, beginning in the 1980s and championed by the rock star Sting, have thus far protected Brazil′s Xingu National Park from flooding by proposed hydroelectric dams along the Xingu River (Turner, 1993; Nugent, 1994).

But the problem with trying to interpret the spread of conservation in terms of successfully fighting and resisting capitalist development is that it suggests a confrontational stance to capitalism in the conservation movement. Dramatic confrontation against construction projects remains the leitmotif of groups like Greenpeace. But, in the main, conservation is more conciliatory and accommodating of the needs of capitalism than it once was (Daily and Walker, 2000). Fights to save places have given way to complicated geographic information system (GIS) software models, which distribute protected areas optimally across the landscape according to such priorities as rarity and vulnerability while minimizing cost. The more sophisticated GIS models specifically include human economic and social needs to reduce the potential for dispute (Sarkar et al, 2006; Wilson et al, 2006, 2007). Many conservationists now work to a simple pragmatic mandate: cooperating with the powers that be in order to protect nature. From this perspective, the growth of protected areas under neoliberal regimes is a testimony to their success in working with the system, speaking comfortable truths to power.

But this again is only part of the story. For it suggests a distance between the values and practices of biodiversity conservation and those of neoliberal capitalism. According to this explanation, conservationists compromise with the demands of capitalism, with humanity′s hunger for resources and industries′ demand for profit, because they have to. But their own values and priorities remain distinct from these dominant forces and values. We do not believe that this is accurate. It is more appropriate to recognize that capitalist policies and values, and often neoliberal policies and values, pervade conservation practice; indeed in some parts of the world they infest it.

If that seems far–fetched, consider the current situation in Laos where the World Bank is currently supporting a US$50 billion dollar project to build a series of dams on the Mekong River. The dams will eventually supply energy to Laos and its neighbours, most notably Thailand, stimulating and sustaining economic growth for years to come. But they come at a huge ecological cost. Thousands of square kilometres of lowland tropical rainforest will be lost, and are indeed now being logged by the Laos military to ensure that as much valuable timber as possible is extracted before the waters rise. But this project has the support of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF, which was one of the organizations that was instrumental in protests against the Xingu Dams in the 1980s). These organizations are able to support the dams in Laos because the project also involves setting up new protected areas in the highlands, safeguarding both the watersheds and the valuable biodiversity therein. Ironically, amidst all the destruction, this is a project that will vastly increase Laos′ protected area network, for it had hardly any prior to this project (Goldman, 2001b).

Situations like the one in Laos are not new. In the 1970s and 1980s the donor– backed Acclerated Mahweli Development Project in Sri Lanka partitioned the landscape into dams, irrigation fields and national parks and moved people around accordingly (Levy, 1989; Stegeborn, 1996; Gamburd, 2000). More recently two new national parks (Campo Maun and Mban et Djerem) have been set up in Cameroon in mitigation for the damage caused by the new Chad–Cameroon oil pipeline, again funded by the World Bank. It is increasingly expected that large projects that damage the environment in some way should provide some sort of compensation. And where they destroy habitat it is only logical that they should protect another place to make good the wrong done. And it is only logical that the developers should seek the advice of conservation experts in the IUCN or WWF to help them to do this properly. Nevertheless the end result is that conservation and capitalism are allying mutually to reshape the world.

It is even possible for mining to increase the amount of space that conservationists find available to conserve. In many parts of the world mining companies are given concessions by governments – large plots of land that they need to drill for oil or mine for ore or gems. The space required for their operations can often be only a small part of the concession. But the remaining land is restricted to local hunters and farmers and can contain untouched vegetation and wildlife (e.g. Laurance et al, 2006). There are also cases of more fundamental alliances forming in which conservation interests and mining interests are (apparently) united to bring profound change to landscapes and livelihoods. Consider the development of the ilmenite (titanium dioxide) mine in the Fort Dauphin area of Madagascar by Qit Minerals Madagascar (80 per cent owned by Rio Tinto and 20 per cent owned by the Government of Madagascar). Rio Tinto claims that the project will provide the catalyst for ‘broader economic development in the country while providing conservation opportunities’ and it will provide ‘net positive benefits, to biodiversity conservation.4 The company has set aside zones in the mining project for conservation, which will form part of the national system of protected areas in Madagascar. It also set up an ecotourism project, which has been running since 2000, to allow local communities to benefit from the conservation initiatives established by Rio Tinto.5

The titanium mine is a perfect example of the global networks that allow the objectives of conservation and capitalism to go hand in hand. Qit Minerals Madagascar has been working with a range of environmental organizations since 1996 to develop social and environmental projects to mitigate the impact of the mine, including the Royal Botanical Gardens at Kew, Missouri Botanical Gardens, Earthwatch and the Smithsonian Institute.6 Indeed, other global conservation organizations operating in Madagascar have taken the decision that they need to work with Qit Minerals Madagascar to gain concessions to conservation and speak in terms that the Malagasy government and mining companies will understand. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as Conservation International have argued that the areas set aside for conservation will be more lucrative in the long term through the development of ecotourism (Duffy, 2008b).

On the other hand, the mine has been severely criticized by Friends of the Earth who argue that the project was threatening unique forest resources and leaving local people struggling to survive in the area affected by the mine. Other researchers note that the case for the mine′s proposed protected areas was based in part on the belief that forests needed protection from local people who were cutting down too many trees. However, satellite data analysis of these forests suggests that this may be a simplistic rendering of environmental change (Ingram, 2004; Ingram et al, 2005). Local communities have complained that the compensation payments are not sufficient since land prices have risen in that area and promises of employment have not materialized.7

These cases are stark examples of conservation and capitalism re–categorizing the landscape together. In many other cases the links and continuities between the two are more subtle – and also more pervasive. They are about changing attitudes to wildlife and landscapes, about introducing markets and commodifying nature, about adapting tourists′ expectations, and tourists′ hosts, and about modifying the societies and communities that live close to valuable nature, about the role models and inspirations that make us conservationists in the first place.

Sklair (2001) has examined the convergence of environmentalism and capitalism in his analysis of the ‘transnational capitalist class’. According to Sklair, this class is composed of corporate executives, bureaucrats and politicians, professionals, merchants and the media who collectively act to promote global economic growth based on the ‘cultural–ideology of consumerism’. He argues that this class is effectively in charge of globalization but also has to resolve crises that arise from its global growth strategy. With respect to environmental problems, he argues, following Gramsci, that corporations and what we call ‘mainstream conservation’ have colluded to form a ‘sustainable development historical bloc’ (Sklair, 2001, p8). The historical bloc offers solutions to the environmental crises that are inherent to global consumer capitalism, while all the time maintaining and strengthening an accompanying ‘consumerist ideology’. Indeed, increased consumption becomes central to the solutions (p216). In this book we extend this perspective to argue that the global proliferation of protected areas and related conservation strategies reflect the emergence of this historical bloc. We argue that although these strategies may limit the growth of industry in some contexts, they simultaneously offer solutions to crises of the global growth strategy that makes the spread of industrial enterprise possible in the first place. Protected areas create new types of value that are essential to the global consumer economy.

In sum, conservation is not merely about resisting capitalism, or about reaching necessary compromises with it. Conservation and capitalism are shaping nature and society, and often in partnership. In the name of conservation, rural communities will reorganize themselves, and change their use and management of wildlife and landscapes. They ally with safari hunters and tourist companies to sell the experience of new tourist products on the international market. In the name of conservation, mining companies, governments, international financial institutions and some conservation organizations work together to achieve common goals that suit the interests of conservation and capitalism. This set of relationships can be counter-intuitive, yet it is clear that they are forming powerful alliances, and can overcome local objections and protest.

As these types of interventions spread and become more sophisticated, it becomes increasingly difficult to determine if we are describing conservation with capitalism as its instrument or capitalism with conservation as its instrument. The lines between conservation and capitalism blur. While it is debatable whether this alliance of conservation and capitalism is capable of saving the world, there is no doubt that it is most capable of remaking and recreating it. One of the central premises of this book, therefore, is that dealing with the types of problems conservationists face will become easier if we recognize the dynamics of capitalism of which they are part. Similarly, understanding the problems conservation causes, how protected areas distribute fortune and misfortune, requires an analysis of the bigger picture of how they are incorporated into the broader economy.

In this book we will be describing, analysing and documenting these changes. We will be considering who wins and who loses from these processes, and what their consequences are for conservationists′ own goals. The book is based on two questions, and structured by two tasks. The questions are:

- In what ways do conservation policies and conservation interventions make wild nature more valuable to capitalist economies?

- With what consequences is this value realized?

The tasks are first, to examine existing knowledge that social scientists have been creating in recent years about conservation policy...