- 188 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Excavations at Glasgow Cathedral 1988-1997

About this book

In 1988 extensive archaeological investigations began at Glasgow Cathedral revealing evidence for the first cathedral built in 1136 and subsequent 12th century phases.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Excavations at Glasgow Cathedral 1988-1997 by Stephen T. Driscoll in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

S Τ Driscoll

1.1 Historical Background

The historical traditions enshrined in the earliest vitae of St Kentigern maintain that Glasgow's ecclesiastical origins are to be found in a small cemetery on the bank of the Molendinar Burn. This cemetery was supposedly consecrated by St Ninian and subsequently adopted by Kentigern as the centre of a see established in the kingdom of Strathclyde in the 6th century. The 12th-century vita of Kentigern succinctly asserts the antiquity of the see of Glasgow and its connections with the earliest evangelists of northern Britain. Although the vitae probably embody some authentic material, the 12th-century reworking of the tradition material is so substantial that all details relating to Glasgow's history prior to the foundation of the see by Earl David (between 1114 and 1118) must be treated with extreme caution. From the 12th century, the historical records become increasingly abundant and allow the rapid development of the see to be charted in some detail. In this Introduction the most important of the documentary sources are briefly reviewed and the major features of the cathedral chapter described. Historical issues relevant to a full understanding of the archaeological evidence include: the status of the bishop and the organisational structure of the chapter, the burgh and its changing relationship to the cathedral, the post-Reformation alterations and modified usage of the cathedral, and the consequences of the restoration work which began in the 19th century. Most readers will probably also find it helpful to have a summary of the architectural development of the extant cathedral, given that all the archaeological work has been framed by the building's present condition.

Apart from Kentigern himself, there is no record of the bishops of Glasgow prior to the 11th century. About 1109 Thomas, Archbishop of York, ordained Michael as bishop of Glasgow. This ordination appears as one in a long sequence of efforts by the bishops of York to assert their authority over the church in Scotland (Durkan 1999). Serious doubt exists as to whether this Michael or his York-ordained predecessors had a significant presence in Glasgow. Apart from the accounts generated in York, nothing is known of these bishops. Nor is there any material evidence from this period at Glasgow; an archaeological blank which is most telling given the great quantities of sculpture known from Govan at this time (Driscoll 1998). According to the contemporary Scottish documentation, the first bishop, John Ascelin, was established in Glasgow between 1114 and 1118 by David I, who at the time was ruler of Cumbria {Barrow 1996, 6; Watt 1991, 54-55). The exact moment of David's endowment is not clear (Shead 1969; Driscoll 1998, no 2), but as early as cl114 David began to provide monies towards the construction of the cathedral (Barrow 1996, 8; 1999, 53-54). Further details of the endowment of the cathedral do not come until 1136, when on the occasion of the dedication of the first cathedral, the results of an inquest instigated by David were recorded. Barrow (1999, 60) believes that the inquest was probably held by David between 1120-21 or 1123-24, but Shead (1969, 223) suggests that the actual enquiry could have taken place somewhat earlier, between 1109-14. The inquest enumerated the extensive holdings of the church of Kentigern, which included lands in the later Barony of Glasgow, the Upper Ward of Clydesdale, Tweedale, Teviotdale, Annandale and probably in Nithsdale. This rich endowment was supplemented by the grant of Govan to the cathedral in 1128-36, again probably on the occasion of the consecration of the new cathedral (Barrow 1999, 72). Also to mark the consecration, the cathedral was granted the royal estate of Partick and various other sources of revenue (Barrow 1999, 80-82). From 1136 onwards the cathedral's history is relatively well known owing to the survival of extensive archives which have been available to scholars since the late 19th century ( Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1

Prospect of Glasgow Cathedral from the north-east from John Slezer's Theatrum Scotiae (1693). The earliest detailed image of the cathedral and precinct. The cathedral shows signs of post-Reformation neglect, but all the main elements of the cathedral ( towers, bishop's castle and the manses) still survive. Reproduced by kind permission of Glasgow University Library

Prospect of Glasgow Cathedral from the north-east from John Slezer's Theatrum Scotiae (1693). The earliest detailed image of the cathedral and precinct. The cathedral shows signs of post-Reformation neglect, but all the main elements of the cathedral ( towers, bishop's castle and the manses) still survive. Reproduced by kind permission of Glasgow University Library

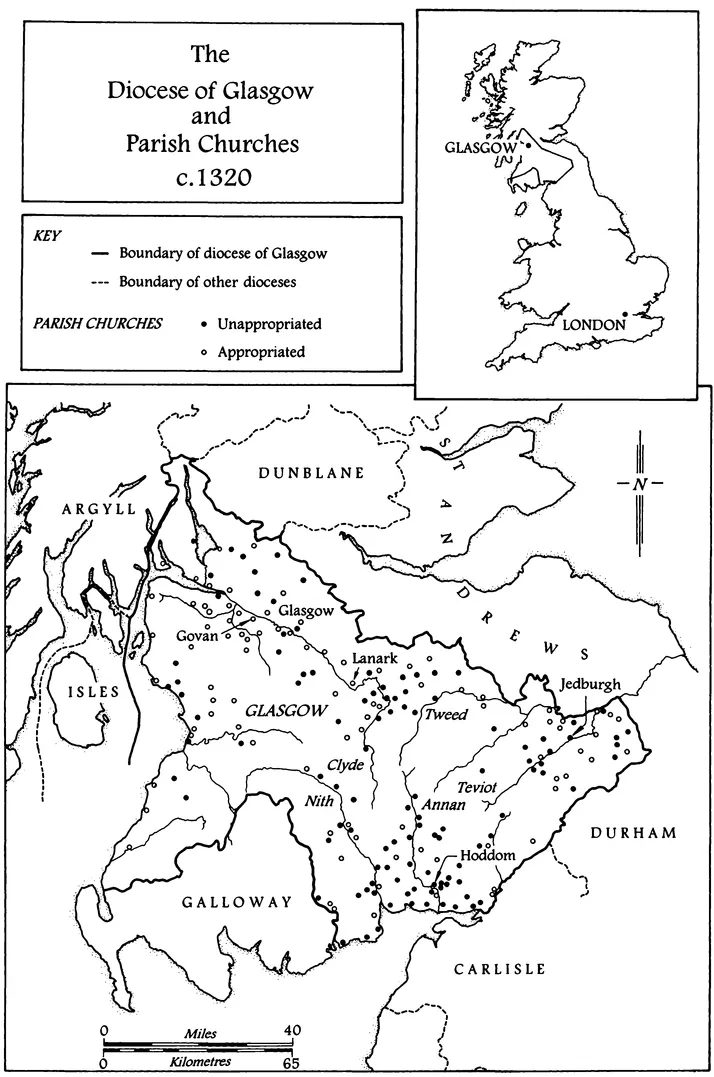

The earliest building was an ambitious Romanesque church, which when completed was probably the most substantial masonry building in western Scotland. On the limited evidence produced by the excavations, the scale of building is hard to substantiate. Rainer Mentel (1988), on the basis of similarities in plan (1998), has argued, however, that the 'giant order' in the Jedburgh Abbey choir (Thurlby 1995) was modelled on the early 12th-century cathedral at Glasgow. If this is true then Glasgow 'marks the starting point of the development of Romanesque architecture in Scotland' (Mentel 1998,48). Glasgow's first cathedral may have fallen some way short of its immediate Romanesque rivals, the great eastern monasteries of Kelso, Holyrood, Dunfermline and St Andrews, which in 1136 were either still under construction or recently completed (Fawcett 1994b, 26-41; Cruden 1986, 26-54, 102). The construction of a major church was entirely appropriate for a diocese fashioned from a former kingdom. As far as can be seen Glasgow's diocese corresponded with the former kingdom of Cumbria. It extended south-east to Tweeddale and Teviotdale, south to Annandale and Carrick (skirting the diocese of Galloway) and north to Renfrew and the Lennox (Figure 1.2). The bishop of Glasgow was the principal ecclesiastical authority over all of the western territory then under the dominion of the king of Scots.

While this study is not intended as a history of Glasgow Cathedral, a number of topics relating to the cathedral's development will be outlined here. This historical overview has been grouped under five headings, which will provide a context for the archaeological discussions to follow. The first topic concerns the authenticity of the traditions surrounding the origins of Glasgow and the activities of Kentigern. The second topic considers the position of the bishop and the organisational structure of the chapter. The third topic is the burgh of Glasgow and its changing relationship to the cathedral. Fourth, the post-Reformation alterations and modified usage of the building are outlined. Finally, the key consequences of the restoration work, which began in the 19th century, are noted.

FIGURE 1.2

The diocese of Glasgow. Dots indicate parishes held before cl320. See map compiled by Norman Shead for the Scottish Historical Atlas (1975,155) for details of parishes

The diocese of Glasgow. Dots indicate parishes held before cl320. See map compiled by Norman Shead for the Scottish Historical Atlas (1975,155) for details of parishes

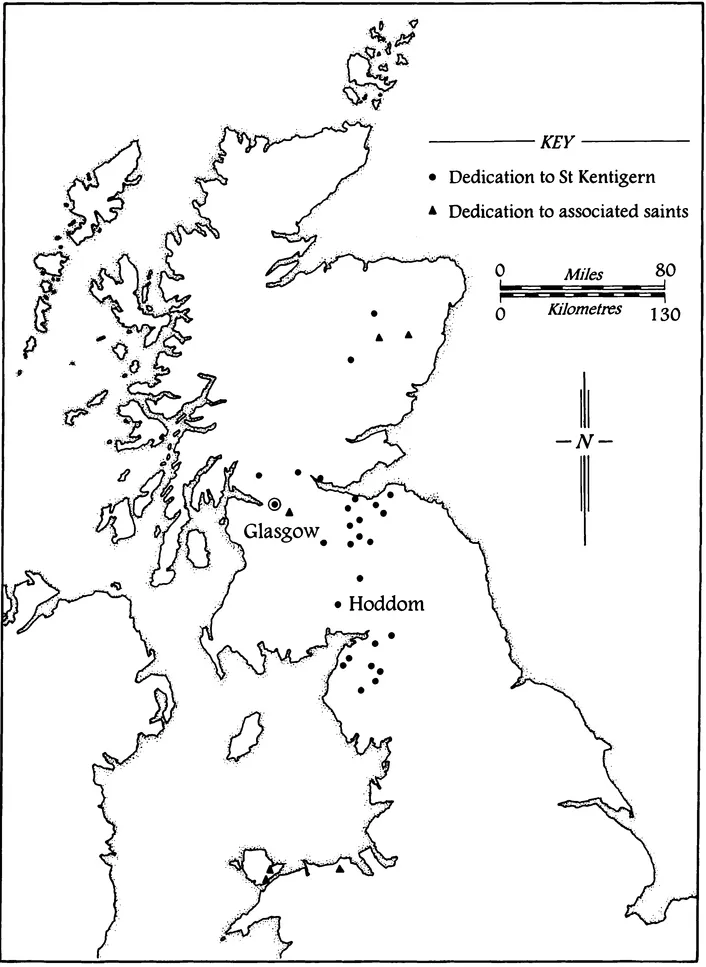

The Kentigern tradition

Using pre 12th-century church dedications as an indicator, it is clear that veneration for Kentigern was strong in Cumbria (Redford 1988, 220-221). Kentigern, also known affectionately as Mungo, has been described as the most important of all the northern saints of Britain (Figure 1.3) (Bowen 1969, 83-84), as evidenced by the eight dedications in English Cumbria (Barrow 1996, 6, no 25). Amongst these Kentigern dedications is the early medieval foundation in Annadale at Hoddom, which was a centre of some importance in the 12th century (Scott 1991). Whatever the importance of these sites for the cult of Kentigern, during the 12th century Glasgow established itself as the most significant centre for this vigorous cult. The clearest indication of this vigour is found in the two 12th-century lives of Kentigern which were commissioned by successive bishops of Glasgow (Forbes 1874).

FIGURE 1.3

The extent of the cult of St Kentigern as indicated by dedications to the saint (circles) or associated saints (triangles). After Bowen (1969, 84) with additions

The extent of the cult of St Kentigern as indicated by dedications to the saint (circles) or associated saints (triangles). After Bowen (1969, 84) with additions

These lives draw upon early medieval material, the historical value of which is difficult to assess and opinions differ widely even as to the date of the earlier strata embedded in the 12th-century versions (MacQuarrie 1997; Jackson 1958). The consensus is that aspects of an authentic 7th-century Kentigern tradition survive within the existing vitae, but the degree to which they have been doctored does not inspire confidence in the uncorroborated detail. For instance, a comparison of the earlier fragmentary vita, compiled during the episcopacy of Bishop Herbert (1147-64), with the version by Jocelin of Furness, completed during the episcopacy of Bishop Jocelin (1175-99), shows a strong hand at work updating and sanitising the vita for a late 12th-century audience (Gardner 1998). Because of the uncertainties surrounding the vitae, only the barest details concerning Kentigern can be accepted as historically correct. Reduced to its essence the tradition maintains that Kentigern was the grandson of the British king of the Lothians, that he was educated by St Serf at Culross and that he became a monk. He travelled to Glasgow to bury a holy man named Fergus at the site of an existing cemetery. As a consequence of political disruptions he travelled widely through Cumbria and lived at Hoddom as well as Glasgow. At the time of this death, around 614 (MacQuarrie 1997, 118), his biographers present him as founder of Glasgow Cathedral, presumably bishop of the northern British. Kentigern was buried at Glasgow and his tomb became a focus of devotion.

The degree to which the tradition has been reworded by Jocelin of Furness and his predecessor means that details relating to this late 6th- to 7th-century church at Glasgow, even simple comments such as the presence of an old cross (Forbes 1874, 110), must be regarded with extreme caution. Probably all that can be accepted without too much doubt is that the cathedral lies near to the site of the early medieval church. This church, almost certainly of timber, was the focus of a cemetery and was served by a Christian community. The landscape setting of the cathedral, its streamside position, its sacred grove (Durkan 1998, 137) and its holy well (built into the existing building), certainly conform to our expectations for a 'Celtic' monastery, but tell us little about the status of this site. The massive size of the parish suggests, however, that Glasgow served as a mother church for the middle stretch of the Clyde and would have served as a suitable seat for a bishop (Durkan 1986a; 1986b; 1998; MacOuarrie 1992).

Whatever the truth about the original status of Glasgow and the subsequent period when Govan seems to have been the principal religious centre on the Clyde (Driscoll 1998), the 12th century saw a burgeoning interest in the cult of Kentigern, no doubt heavily encouraged by the newly written vitae. Enthusiasm for the cult is clearly apparent in the flurry of building work, which saw a succession of three major campaigns of enlargement within the space of a century and culminated in the completion of the existing cathedral. Less than 50 years passed from the dedication of John's cathedral to the beginning of major enlargements in 1181 during the episcopacy of Jocelin (1174-99). This work was delayed by fire but had progressed enough for a part to be dedicated in 1197, however it was never completed and was replaced by an even larger building which was begun around 1200. As the excavations showed these successive phases of building and enlargement were all within a relatively limited area, and the fixed point throughout was probably the presumed site of Kentigern's burial. This rapid expansion in the late 12th century is one of the remarkable aspects of the cathedral's history, which coincides with the growth in importance of the burgh itself under the lordship of the bishop.

Bishop and chapter

For most of its history Glasgow was the second most important see in Scotland, after St Andrews, but at times the bishops of Glasgow were the leading ecclesiastics in the kingdom. This importance is reflected in the frequency with which the bishop served as a royal official. There was a natural political dimension to the construction and leadership of a see which by cl320 included 206 parishes (Shead 1975; 1988). With the establishment of the cathedral, the bishop became the most powerful lord in Cumbria, and his influence extended far beyond Clydesdale to include the Lennox and the Borders. The bishops were fundamental to the government of the west, but they followed more wide-ranging briefs. The first bishop, John (1114-18 to 1147), served as a papal envoy whose main goal was to secure recognition that the Scottish church was independent and outwith the authority of the archbishopric of York. The bishops of Glasgow also acted as brokers in awkward internal affairs such as the revival of the see of Dunblane. Perhaps the most regular, consistent contribution to governing Scotland made by the bishops was as chancellor: no fewer than eleven held this office (Dowden 1912).

The importance of the see is also reflected in the size and nature of the chapter, which from an early date adopted the practices of Salisbury. The needs of the chapter, particularly with respect to the liturgical rites, had a strong influence on the design of the cathedral church itself. It seems fairly clear that Glasgow Cathedral and its chapter were modelled upon the secular cathedrals developed in northern France, which were a prominent feature of the Norman world (for example, Bayeux, York, Lincoln and Salisbury) (Barrow 1996, 8-9). The cathedral chapter bore little resemblance to 'Celtic' or, indeed, to Benedictine monasteries, although the canons did fulfil similar liturgical roles. The college of canons maintained a rich programme of worship and catered for the pastoral needs of pilgrims, but they also had parochial responsibilities. Members of the chapter held prebends (incomes) from the parish in exchange for seeing to the pastoral needs of the parishioners. From a royal perspective one of the main advantages of this sort of organisation was that it was free of interference from a religious order. It was not however free from outside influences or organised for the convenience of the bishop or the king.

The chapter was initially composed of at least six canons governed by 'old and reasonable customs', but by the time of Bishop Herbert (1147-64) the number of canons had grown to 25 and been formally constituted (Barrow 1996, 10-11). In 1259 Glasgow Cathedral obtained from the dean and chapter of Salisbury an account of constitu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Synopsis

- Summary

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 1.1 Historical background

- The Kentigern tradition

- Bishop and chapter

- Architectural history

- The burgh and the cathedral

- Post-Reformation changes

- Modern restoration

- 1.2 Account of the excavations

- Previous archaeological investigations

- Recent work

- 1.3 The recording system

- The archive

- 1.4 Post-excavation research programme

- 1.5 Phasing

- 1.6 The radiocarbon dates

- 2 Archaeological structures

- 2.1 The nave

- Phase 1: pre 12th-century activity

- Phase 2: cathedral of Bishop John (early 12th century)

- Phase 3: cathedral of Bishop Jocelin (late 12th century)

- Phase 4: early 13th-century cathedral

- Phase 5: completion οf the laying out of the nave (mid 13th century)

- Phase 6: burial activity in the nave (13th-17th centuries)

- Phase 7: post-Reformation structures and burials (17th-19th centuries)

- Phase 8: modern refurbishment (1835-present)

- 2.2 The crypt

- Crypt E trench

- Phase 4: early 13th-century cathedral

- Phase 7: post-Reformation structures and burials (17th-19th centuries)

- Phase 8: modern refurbishment (1835-present)

- Other archaeological investigations

- Summary

- 2.3 The choir

- Phase 4: early 13th-century cathedral

- Phase 7: post-Reformation modifications (17th-19th centuries)

- Phase 8: modern refurbishment (1835-present)

- 2.4 The treasury (session room)

- Phase 4: early 13th-century cathedral

- Phase 7: post-Reformation structures and burials (17th—19th centuries)

- 2.5 The western towers

- The NW tower

- The SW tower

- 2.6 Excavations for services to the NE of the cathedral

- Trench 1

- Trench 2

- Discussion

- 3 The finds and environment

- 3.1 Introduction

- 3.2 Architectural stonework

- Phase 2: cathedral of Bishop John (early 12th century)

- Phase 3: cathedral of Bishop Jocelin (late 12th century)

- Phases 4-5: early to mid 13th-century cathedral

- Catalogue of carved architectural material

- 3.3 Late 12th-century architectural polychromy

- Art-historical analysis

- Scientific examination

- Conclusions

- 3.4 Coffins and coffin furniture

- Wooden coffins

- Coffin furniture

- Decorative assemblages from individual coffins

- Discussion

- 3.5 Metalwork

- Small copper-alloy objects

- Seal matrix

- Bronze mortars and iron pestle

- Iron objects

- 3.6 Coins

- 3.7 Pottery

- 3.8 Clay tobacco pipes

- 3.9 Other finds and materials

- Post-medieval gravestones

- Plasterwork

- Mortar

- 3.10 Environmental evidence

- Introduction

- Carbonised plant remains

- The animal bones

- 4 Human skeletal remains

- 4.1 Introduction

- 4.2 The skeletal remains from the nave, crypt, choir and treasury

- Introduction

- Methodology

- Results

- 4.3 Two skeletons from the NW tower

- Preservation

- Results

- Conclusions

- 4.4 Human remains from the surroundings of the cathedral

- 4.5 Botanical analysis of soil from the pelvic region of six skeletons

- Method

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- 4.6 Insect fauna from within the cranium of skeleton 570

- 5 Concluding discussion

- Burial and worship

- Two 12th-century cathedrals

- High medieval to post-medieval

- Finds

- Wider implications

- Appendix

- The radiocarbon dates

- Plasterwork

- Mortar analysis

- Bibliography

- Index