![]()

PART I

Foundations of psychosocial health

Before focusing on specific threats to athletes’ psychosocial health, or proposing ideas for the prevention and management of psychosocial health issues, it is first necessary to provide a conceptual foundation and establish a common language from which to discuss these issues. Although in practice it is nearly impossible to consider the different domains of health and well-being in isolation, for didactic purposes it is beneficial to consider them separately. In Chapter 1, I define key terms, offer an overview of research on well-being in sport, and highlight the importance of considering the psychosocial aspects of health for both athletic performance and global well-being.

In Chapter 2, I introduce the cognitive and emotional domains of psychosocial health. Due to its implications for skill-learning and within-competition decision-making, the cognitive domain of psychosocial health is especially linked to sport performance. Beyond performance, sport can serve both as an enhancer and debilitator of important cognitive functions. Emotional health (often referred to as mental health) has received increased attention from elite sport organizations, due in part to several high-profile athletes speaking out about their conditions. Scholarly research on emotional health in athletes has also increased, and I share important findings relative to the prevalence of emotional health issues in sport, as well as the conditions under which sport may serve as a risk or protective factor for such issues.

Finally, Chapter 3 highlights the relevance of social and spiritual health for high-level athletes. Social health has most often been examined through the lens of Keyes’ (1998) theory of social well-being, which is one component of psychological well-being. In addition to reviewing two studies of social well-being in athletes, I synthesize the literature related to social support. I conclude the chapter with an introduction to spiritual health, which has most often been studied in athletes as spirituality or religiousness. Specifically, I discuss research suggesting competitive sport as an ideal site for the expression and realization of spiritual health, as well as the link between spiritual health and the emotional and social dimensions of psychosocial health.

![]()

1

The relevance of psychosocial health for high-level athletes

Garrett is a professional basketball player who has recently been traded to a new team. As part of the trade, his new team requires him to undergo a physical exam to ensure that he is healthy to train and compete. The exam is comprehensive, and includes questions on Garrett’s medical history (e.g., past injuries), as well as biometric assessments such as heart rate, blood pressure, vision, and a general evaluation of posture, range of motion, and muscle strength. The physician gives Garrett a clean bill of health, and the trade is finalized. Things are going well until about mid-season, when Garrett begins arriving late to practice, missing team meetings, and performing below his usual standard. Upon being confronted by his coach and teammates, Garrett admits to having struggled on-and-off with his emotions for several years and agrees to get help from a mental health professional. After his in-take session with the therapist, Garrett is diagnosed with major depressive disorder, and begins a program of medication combined with regular psychotherapy. The front-office staff decides that future physical exams should go beyond the physical aspects of athletes’ health.

High-performing athletes are revered for their remarkable feats of strength, speed, and endurance. Elite-level endurance athletes such as cross-country skiers can use almost twice the amount of oxygen as a typically trained adult (Hutchinson, 2014), and weightlifters who compete at the Olympics routinely lift two to three times their body weight from the floor to above their heads (Anon., 2012). Athletes in team sports possess an uncanny ability to quickly assess the situation and react to constantly changing circumstances, all while coordinating their actions with those of their teammates. Athletes who have achieved such impressive feats on the playing field are often called upon to be role models of healthy living (Lisanti, 2017). Paradoxically, these same high-performing athletes often struggle with a variety of health issues, including life-altering injuries, coach abuse, drug and alcohol dependence, and disordered eating behaviors (Safai, Fraser-Thomas, & Baker, 2015). Unfortunately, as seen in the hypothetical case of Garrett, such issues are often taken for granted by sport organizations.

The varied meanings of health

Before engaging in a critical discussion of athlete health, it is first necessary to discuss both how the term is commonly used in sport, as well as define how it will be used in this text. To illustrate the typical view of health in sport, imagine the head coach of a high-level team addressing the media prior to an important game or match. As reporters pepper her with questions, the subject of certain team members’ health naturally arises. Regardless of her response, the implied context is the physical status of the athlete in question. An expected answer might be “Player X has been cleared by the team doctor to play in today’s game,” or “Player Y has a stomach virus and will be out of action tonight.” Such answers reveal important assumptions about the nature of health. First, it seems clear that the coach has adopted a medical-model view, in which health is viewed as the mere absence of disease or injury (Laing, 1971). Second, it is exceedingly rare for a coach, athlete, or team official to address athlete health from a holistic perspective; instead, they tend to reduce the issue to one of physical illness or injury. That is, even if an athlete was struggling with a psychosocial health concern such as a bout of depression that put his ability to play in jeopardy, such issues are usually either not discussed, or not immediately considered as fitting under the purview of athlete health.

In this text I will adopt the World Health Organization’s more versatile definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 1946). Although some health concerns of athletes, such as injury, have clear physical implications, rarely are the antecedents and consequences of such concerns purely physical. Depending on the severity of the injury, athletes can expect to experience a variety of cognitive, emotional, social, and even spiritual challenges in the process of recovery (Clement, Arvinen-Barrow, & Fetty, 2015). Substance dependence, although certainly a physical threat to athletes, is also often the result of social pressure to perform, and can in turn have profound psychological effects (Whitaker, Long, Petróczi, & Backhouse, 2013). Thus, a more complete approach to athlete health extends beyond the physical to include the cognitive (i.e., thinking), emotional (i.e., feeling), social (i.e., relating with others), and spiritual (i.e., connection with something greater than oneself) dimensions (Donatelle, 2015). For example, a collegiate volleyball player who recently transferred to a different university will ideally learn the strategy of her new team at an appropriate rate (i.e., cognitive health), effectively cope with the stress of transition (i.e., emotional health), form new productive relationships on and off the court (i.e., social health), and feel a sense of purpose and fulfillment as it relates to her academic and athletic career (i.e., spiritual health).

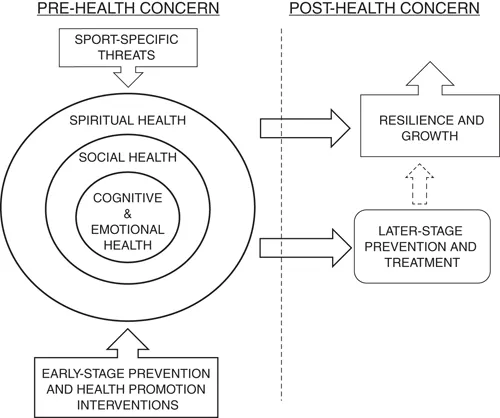

Taken together, these four dimensions of psychosocial health can be viewed as an indicator of athletes’ well-being, or “diverse and interconnected physical, mental, and social factors extending beyond traditional definitions of health” (Naci & Ioannidis, 2015, p. 121). As depicted in Figure 1.1, athletes’ psychosocial health and well-being are under constant bombardment from threats such as injury and transition (see Chapters 4–8). With careful planning, negative health concerns can be prevented (see Chapters 9–10). However, even the best prevention cannot eliminate all health concerns, and later-stage prevention and treatment are often warranted (see Chapter 11). Finally, for some athletes, the experience of health concerns and/or the process of treatment may be an opportunity for displays of resilience or the realization of personal growth (see Chapter 12).

FIGURE 1.1 A conceptual model for understanding psychosocial health in high-level athletes

Well-being

Because the concept of well-being is, in and of itself, of interest to sport researchers, it warrants specific consideration. Numerous scholars have offered models of well-being in the general population, which usually involve some combination of social and emotional dimensions. For example, in his tripartite model of subjective well-being, Diener (1984) posited that degree of positive and negative affect (i.e., affective balance) and life satisfaction determine individuals’ well-being. Ryff’s (1989) six-factor model of psychological well-being emphasizes the factors of self-acceptance, personal growth, life purpose, environmental mastery, autonomy, and positive relations with others as forming the foundation of well-being. Central to current conceptions of well-being is the distinction between hedonic well-being (i.e., subjective well-being), or individuals’ subjective experiences of happiness, and eudaimonic well-being (i.e., psychological well-being), or the extent to which individuals pursue meaningful goals leading to personal fulfillment. A further component of psychological well-being (PWB) is social well-being, or individuals’ perception of the extent to which their social life is flourishing (Keyes, 1998). Social well-being is further divided into five components: (a) social acceptance, (b) social actualization, (c) social contribution, (d) social coherence, and (e) social integration. Each of these five components is discussed in Chapter 3.

It s...