eBook - ePub

Consistency and Cognition

A Theory of Causal Attribution

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1983. Theories of causal attribution fall into two areas- those that are concerned with the basic psychological processes underlying causal attribution and those that deal with the motivational, affective, and behavioral consequences of causal assignation. The authors of this study explore the first theory theory based on one major assumption. Causal attribution is a manifestation of the tendency for consciousness, as a system, to organize cognitive content, that is, cognitions, into the simplest structures possible.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Consistency and Cognition by S. Duval,V. H. Duval,F. S. Mayer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Concepts and Theory

Heider (1944, 1958) as well as other psychologists propose that consciousness prefers simplicity. This preference implies that consciousness is a dynamic process that moves to maximize simplicity within its boundaries. Simplicity is an inverse function of the number of separate and unconnected elements in consciousness (i.e., diversity). Maximum simplicity represents the case in which all elements are connected (i.e., minimal diversity). We submit that causal attribution is a manifestation of this movement to maximize simplicity within consciousness. Specifically, awareness of a discrete event that is not spontaneously assimilated to any preexisting cognitive structure decreases simplicity of cognitive organization by increasing the number of separate and unconnected elements in consciousness. The movement toward maximizing simplicity in terms of minimizing diversity connects the event with other elements present in consciousness. The formation of these higher order cognitive structures, which Heider refers to as unit formations, reduces diversity because the previously separate element (i.e., the event) is now connected to another or other elements. If one element of a unit formation is defined as an "effect" event and is connected with another event such that they become temporally ordered aspects of a single extended cause-effect sequence, then the unit-formation process is a process of causal attribution. The fact that the elements of a cause-effect unit formation are connected and thus reflect the movement to maximize simplicity is clearly demonstrated by Michotte's (1963) research on the phenomenological characteristics of perceived physical causality. If the movement of an object (B, the effect event) is perceived as caused by contact with another moving object (A), then B's movement is seen as a continuation of the movement of A rather than as a discrete and separate event. The fact that observing or thinking of the occurrence of one element in the cause-effect unit (e.g., a person observes someone turning on the ignition switch of a car) tends to call to mind the other event included in that formation (the person expects the car's engine to start) is further evidence that previously separate cognitions (i.e., turning on the switch, the starting of the engine) are now elements of a single, although extended, cognitive structure.

The movement toward maximum simplicity in terms of minimizing diversity explains why cause-effect units are formed. The attribution process connects events in cause-effect unit formations in order to reduce the number of separate, unconnected elements in consciousness and thus reduce the diversity within that system. However, we must point out that this process is not indiscriminate. A particular effect is not simply connected with all other events in consciousness nor does each event in consciousness have an equal probability of being connected with the effect in a cause-effect unit. These facts suggest that simplicity of consciousness is not solely a function of diversity in the system. A discussion of this issue follows.

In general, it seems reasonable to assume that unit formations made up of elements that are consistent with each other are simpler than unit formations made up of inconsistent elements. This assumption implies that simplicity of consciousness is a function of the degree of consistency between the elements of unit formations as well as the extent to which elements in consciousness are connected together. Specifically, to maximize simplicity the elements in consciousness would not only have to be connected, but connected in units made up of elements that are maximally consistent with each other. Maximally consistent is defined as the case in which the elements of unit formations are more consistent with each other than with any other elements in consciousness.

It now appears that simplicity within consciousness is a function of two factors: diversity and consistency. Inasmuch as we have argued that causal attribution is a manifestation of the tendency to maximize simplicity, the dynamics of the causal-attribution process should reflect the operation of these two factors. Movement toward maximum simplicity in terms of minimizing diversity predicts the general tendency to connect effects and other events in cause-effect unit formations; movement toward maximum simplicity in terms of maximal consistency predicts which particular events will be linked with specific effects in cause-effect units. To achieve maximum consistency in cause-effect unit formations, the attribution process tends to join a particular effect with the event that is more consistent with it than are other events present in consciousness. If the person becomes aware of an event that is even more consistent with the effect than the event previously linked with that effect, the tendency to generate maximally consistent cause-effect unit formations will reorganize cognition so that the more consistent event becomes linked with the effect in a new cause-effect unit.

We have proposed that causal attribution represents the constructive processes of cognitive organization. Within consciousness, the movement toward maximum simplicity leads to the organization of effects and other events into higher order cause-effect unit formations whose elements (i.e., the cause and the effect) are maximally consistent with each other. The following example illustrates the hypothesized operation of this dynamic process.

An instructor finds that the class average on a midterm exam is unusually high. On the same day he receives a phone call from a lawyer informing him that his wife is filing for divorce. In neither case is the cause for these events readily apparent (i.e., the instructor does not immediately know why the exam scores were higher than usual nor why his wife is filing for divorce). Now let us assume that the set of events present in the instructor's consciousness is limited to the following: (1) he has recently suffered substantial financial losses; (2) that semester, he changed the format of the lectures presented to his class; (3) his car would not start that morning; (4) he had an argument with his wife concerning the condition of their lawn; (5) the air conditioning was working in the classroom for the first time in several days when the midterm exam was given; (6) his neighbor had a baby on the morning of the midterm. Later, we find that the instructor has attributed causality for the high test scores to the change in the format of his lectures, although he remains somewhat bothered by the fact that he did not actually change the format very much. We also discover that he has attributed causality for his wife's actions to his recent financial setbacks, but he recalls that, even though she was upset, his wife seemed to cope with the financial problems fairly well. On the following day, his teaching assistant informs him that the tests were scored incorrectly. He reattributes causality for the unusually high scores to the error in grading. He also speaks to his wife that day, and she informs him that she is desperately in love with another man. He reattributes his wife's request for a divorce to her relationship with the other man.

The example presents a sequence of events typical of the attribution process. The person first becomes aware of an effect (or effects) for which the cause is not known and then attributes causality for that effect to some other event. If an event that seems to be a better causal explanation is discovered, reattribution occurs. From the present point of view, the events associated with this process reflect the tendency for consciousness to maximize simplicity within its boundaries. First, awareness of two effects (the high test scores and his wife's actions) that were not spontaneously assimilated to preexisting structures decreased simplicity within consciousness by increasing the number of unconnected elements present in the system. To increase simplicity in terms of minimizing diversity, each effect was connected with another event in a cause-effect unit formation (i.e., the instructor attributed causality for the high exam scores to a change in the format of his lectures and for his wife's actions to recent financial losses). To increase simplicity in terms of achieving maximum consistency between the elements of each unit formation, the events connected to the effects as causes were the events that were more consistent with the effects than were other events present in consciousness at that point in time. The instructor initially attributed causality for the high test scores to the change in lecture format rather than to some other event present in consciousness (e.g., his recent financial losses, the fact that his neighbor had a baby on the morning of the exam, the air conditioning) because the change in lectures was more consistent with the high test scores than were the other events. He initially attributed causality for his wife's behavior to his recent financial losses rather than to some other event present in consciousness (e.g., changing the format of his lectures, the argument over the condition of the lawn, the failure of his car to start that morning) because recent financial losses were more consistent with his wife's filing for divorce than were the other events. Furthermore, when presented with events (i.e., the error in grading and his wife's affections for another man) that were even more consistent with the effects than those that had first been seen as the cause, the instructor reattributed causality to the more consistent events.

To illustrate our approach to causal attribution, we have analyzed a hypothetical example in terms of the dynamics that we think govern the attribution process. Of course, the persuasiveness of this analysis is dependent on the reader's agreement with our intuitive assessment of the degrees of consistency among the various effects and the other events in the instructor's consciousness. In the following section, we present a more formal definition of our concept of consistency and discuss the general operation of that dynamic in causal attribution.

The Consistency Principle

First, our consistency principle deals with the degree of consistency between the properties of effects and other events. A property will be treated as any attribute of effects and events that either has magnitude or can otherwise be measured and represented dimensionally. For example, the position of effects and events in time is a property because it can be measured and represented dimensionally. The degree of affectivity associated with effects and events is also a property because affect has magnitude and can be represented dimensionally (i.e., magnitude of positive versus negative affect).

Second, we originally proposed (Duval & Hensley, 1976) that

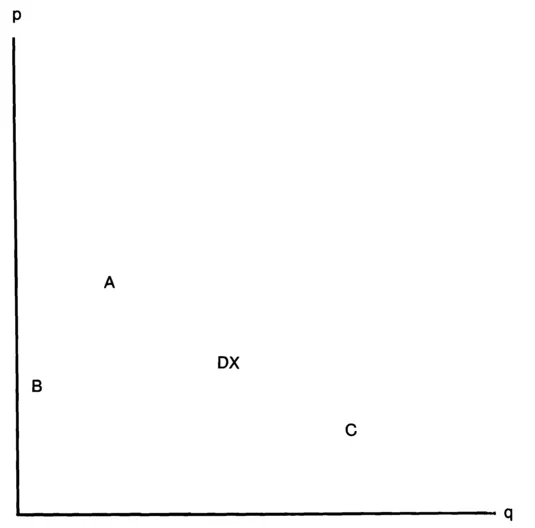

FIG. 1.1 Causal attribution as a function of similarity between effect event X and possible causes A, B, C, and D.

the consistency principle applicable to the causal-attribution process refers to the degree of similarity between the properties of effects and properties of other events. As the degree of similarity between the properties of an effect and another event increases, the degree to which the effect and the event are consistent also increases. From this perspective, the tendency to maximize simplicity in consciousness in terms of achieving maximum consistency within unit formations would produce an attribution of causality for a particular effect to that event with properties that are more similar to those of the effect than are the properties of other events present in consciousness. For example, let us assume that the person is aware of an effect (X) and several events (A, B, C, D). This effect as well as all other events have properties p and q. In this case the properties have magnitude. The effect has five units of p and five units of q. The magnitude of the p and q properties associated with the other events varies widely. This situation is illustrated in Fig. 1.1. The effect and the events are represented as points on a two-dimensional plane. The dimensions are defined by the p and q properties of both the effect and the other events. The positions of the effect and the other events on this two-dimensional surface are determined by the magnitude of the p and q properties associated with each. The degree of similarity between the effect and each event is represented by the distance between their positions on the graph with decreasing distance indicating increasing similarity and vice versa. Strict application of the consistency principle to this situation predicts that causality for the effect will be attributed to the event with properties that are most similar to the properties of the effect in terms of the absolute distance between them (in this case, event D). If the situation includes two or more events that are equal in similarity to the effect on the p and q dimensions, application of the consistency principle predicts an equal tendency to attribute causality to each of those events.

The consistency principle as applied to causal attribution predicts that causality for an effect will be attributed to the event with properties that are more similar to the properties of that effect than are those of other events in consciousness. However, at this point, we must take the asymmetrical form of cause and effect structures into account. This asymmetry demands that events have certain features before they qualify as possible causes for particular effects. Because present application of the consistency principle is limited to processes that result in cause-effect unit formations, the following section discusses factors that determine which events qualify as possible causes for given effects.

The Asymmetry Criteria

Tversky (1977) has identified two distinct types of relationships: symmetrical and asymmetrical. In symmetrical relationships, the elements are not rank ordered. E = MC2 is an example of this type of relationship. E and MC2 are treated as identities, and E does not follow from MC2 to any greater extent than MC2 follows from E. Asymmetrical relationships, on the other hand, involve elements that are rank ordered such that one (the variant) follows from the other (the prototype), but the reverse is not true. Tversky offers the relationship between father and son as an example of an asymmetrical relationship. The son (the variant) follows from the father (the prototype), but reversing the rank order between the two elements (the father follows from the son) seems odd or nonsensical. The relationship between a person's portrait and that actual person is similarly biased. The portrait (the variant) follows from the person (the prototype), but a reversal in this rank order (the person follows from the portrait) again seems odd or nonsensical.

Cause and effect relationships are clearly asymmetrical rather than symmetrical. The effect follows from the cause, whereas the reverse is not true. For example, we are at a party and hear a person say something nasty to a particular lady. The lady then faints. We believe that the nasty communication caused the woman to faint. Given this attribution, we would say that the physical act of fainting (the effect) followed from the nasty communication (the cause). We would not say that the communication (the cause) followed from the physical act of fainting (the effect). Similarly, if we are watching a game of pool and see the cue ball strike the eight ball which then moves toward the side pocket, we would say that the movement of the eight ball (the effect) followed from contact with the moving cue ball (the cause). We would not say that the movement of the cue ball followed from the movement of the eight ball (i.e., that the cause followed from the effect).

The asymmetry of cause and effect relationships implies that the elements connected in cause-effect unit formations must, to use Tversky's language, be related to one another as prototype and variant. The causal event must have the status of prototype; the effect event must have the status of variant, with prototype and variant representing a dichotomous variable (i.e., one that does not vary in degree). The existence of this asymmetry suggests that the set of events that could possibly be linked to a particular effect as a cause are limited to those events that meet at least two criteria. First, the events must possess some feature that causes them to have the status of prototype relative to the effect in question (i.e., the effect would follow from the events and not vice versa). Second, the event...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Concepts and Theory

- 2. Time and Space

- 3. Focal Consciousness

- 4. Novelty I

- 5 Novelty II

- 6. Affect

- 7. Defensive Attribution

- Epilogue

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index