![]()

Part I

Development and Instruction

![]()

1

Psychological Models for the Development of Mathematical Understanding: Rational Numbers and Functions

Mindy Kalchman

Joan Moss

Robbie Case

University of Toronto

The domains of rational number and functions are foundational to many topics in advanced mathematics, and underpin the understanding necessary for participation in the pure and applied sciences (Lamon, 1999). Both domains are also known to be extremely difficult to master. Although many students do eventually learn to perform the basic operations and algorithms that the domains require, their conceptual knowledge remains remarkably weak, as does their ability to tackle novel problems (Carpenter, Fennema, & Romberg, 1993; Harel & Dubinsky, 1992). In this chapter, we discuss a program of research in which we have been trying to model the conceptual understanding that underpins novel performance in these two domains on the one hand, and to design improved curricular approaches for developing this sort of conceptual competence on the other.

The particular form of conceptual competence that we have been interested in has been characterized as number sense. As a number of authors have pointed out, the characteristics of good number sense include (a) fluency in estimating and judging magnitude, (b) ability to recognize unreasonable results, (c) flexibility when mentally computing, (d) ability to move among different representations and to use the most appropriate representation for a given situation, and (e) ability to represent the same number or function in multiple ways, depending on the context and purpose of this representation (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1996; Case, 1998; Greeno, 1991; Sowder, 1992).

Our primary psychological assumption about number sense is that it depends on the presence of powerful organizing schemata that we refer to as central conceptual structures. We believe that these structures, which we model as complex networks of semantic nodes, relations, and operators, represent the core content in a domain of knowledge, help children to think about the problems that the domain presents, and serve as a tool for the acquisition of higher order insights into the domain in question. In an earlier series of articles, we proposed that central conceptual structures are normally assembled by the integration of two intuitive or “primitive” schemata. The first of these is primarily digital, verbal, and sequential; the second is primarily spatial, analogic, and nonsequential (Case & Okamoto, 1996; Griffin & Case, 1997; Kalchman & Case 1998; Moss & Case, 1999). In the first phase of children's learning (which we shall refer to as Level 1), these two core schemata are consolidated in isolation. In the second phase (Level 2), both of these two early schemata become more complex, while at the same time they are mapped onto each other. The result is that the students' understanding of the domain is transformed and a new psychological unit is constructed. During the next phase (Level 3), students slowly begin to discriminate among the different contexts in which the new unit can be applied, and to create slightly different representations of it–each with its own distinctive properties. In the final phase (Level 4), students build explicit representations of how these different variants of the core structure are related to each other, and learn to move among them freely and fluently depending on their purpose. More than anything else, it is this flexible movement that demonstrates that children have acquired true number sense, and not just a set of isolated conceptual understandings and algorithms.

In order to understand the way in which this general progression takes place in mathematics, it is useful to consider a concrete example. Consider, therefore, the domain of the whole number and the central conceptual structure on which children's number sense depends. According to the model proposed by Case and his colleagues (Griffin & Case, 1997; Okamoto & Case, 1996), the two primitive schemata on which the development of whole number depends are the schema for verbal counting (digital, sequential; Gelman, 1978), and the schema for global quantity comparison (spatial, analogic; Starkey, 1992). Although young children have strong intuitions for both counting and global quantity comparisons, these two schemata initially develop separately. Evidence in support of this assertion comes from several sources. In a recent factor analysis, Okamoto and her colleagues (personal communication, February 14, 2000) found two factors at this age level that corresponded with counting and quantity evaluation. Other evidence includes the fact that children have difficulty answering a question posed in one mode (e.g., verbal/sequential) that depends on the other mode for its answer. For example, they have a hard time answering the question “Which is more, 5 or 4?” although they can count to 5 without error, and can pick out an array of 5 objects as the larger, when it is contrasted with an array of 4 objects (Griffin, Case, & Siegler, 1994; Okamoto & Case, 1996; Siegler & Robinson, 1982).

As children make the transition to a higher level of cognitive development (Level 2) at about the age of 6, and as their thinking is stimulated by the numerical problems that they encounter at home and in school, they gradually elaborate on these two schemata and map them onto each other. Factor analytic studies now reveal a single factor, and children can answer a variety of questions requiring the coordination of the two initial schemata. Their new structure also permits them to solve a wide variety of cross-modal questions, including symbolically or verbally posed addition and subtraction problems, which they solve by counting forward and backward along the verbal counting sequence (Fuson, 1992; Siegler, 1996). In Okamoto's study, a single factor also emerged at this age level among the more advanced students.

As children begin to understand how mental counting works, as they continue to encounter problems that require mental counting, and as they continue to develop more generally, they move on to the next phase (Level 3), typically at about the age of 7 years. During this phase of their learning, they gradually form representations of multiple number lines, such as those for counting by 2, 5, 10, and 100. The construction of these representations gives new meaning to problems such as double digit addition and subtraction, which can now be understood as involving separate number lines, one for 10s and one for 1s.

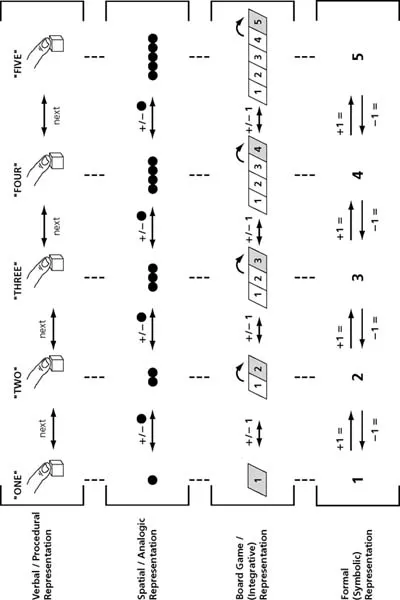

In the final phase of their learning about whole number (Level 4), which typically begins around 9 or 10 years of age, children gradually develop both a generalized and an explicit understanding of the entire whole number system and the way in which different forms of counting are related to each other. Addition or subtraction with regrouping, estimation problems using large numbers, and mental math problems involving compensation are all understood at a higher level as this understanding gradually takes shape. The progression through the various phases is summarized in the second column of Table 1.1. The central numerical structure (the “mental number line”) that emerges in the second phase is illustrated in greater detail in Fig. 1.1. The

TABLE 1.1

Modelling the Development of Conceptual Understanding In Three Different Mathematical Domains | Level of Understanding | Mathematical Domain |

| Whole Numbers | Rational Numbers | Functions |

Level 1:

Consolidation of primitive schemata

A: digital

B: analog | A: Counting schema B: Qualitative quantity schema (more/less; addition & subtraction). | A: Formal halving and doubling schema, for numbers from 1 to 100

B: Qualitative proportionality schema, including visual halving and doubling. | A: Recursive computation schema

B: Bar graph schema |

Level 2: Construction of new element

A-B | Mental number line, with counting as an operation that is equivalent to addition and subtraction | Rational number line, with each number half of double previous one (e.g., whole, 1/2, 1/4, 1/8, or we believe more appropriately; 100%, 50%, 25%, 12.5%) | Function schema, with line on Cartesian graph understood to represent results of iterative computation for different values of x |

Level 3: Differentiation of new elements

A1 – B1; A2 – B2 | 1s, 10s, 100s, and their relationship, understood and generalized to full whole number system | Decimals, fractions, percents, and their relationship understood | Confusable functions differentiated from each other, (e.g., y = 2x; y = x2; y = 2x. Function as object differentiated from function as sequence of operations |

Level 4: Understanding of full system

A1 – B1 × A2 – B2 × A3 – B3 | 1s, 10s, 100s, and their relationship, understood and generalized to full whole number system | Decimals, fractions, percents, and their relationship understood | Elements of polynomial (x, x2, x3) and the way they can relate, understood. |

FIG. 1.1. Central conceptual structure for whole number. The four rows indicate different representations. The horizontal arrows indicate an understanding of the relation between adjacent items within each different type of representations. The vertical lines indicate that subjects understand the equivalence of these different representations, and the relations between them.

integrative representation in the middle of the figure is one that we have found useful in helping children to differentiate, elaborate, and integrate their earlier analogic and digital representations of numbers in our instructional studies (Griffin & Case, 1997).

How general is the psychological progression that is illustrated in Figure 1.1? How general is the sort of reciprocal mapping that the structure illustrates? How general is the finding that an integrative external representation, appropriately used, can facilitate the internal process of integration, thus deepening children's conceptual understanding and improving their number sense? (Case, 1985; Case & Griffin, 1990). In the present study, we investigated all three of these questions, and came to the conclusion that all three processes are quite general indeed.

UNDERSTANDING IN THE DOMAINS OF RATIONAL NUMBER AND FUNCTIONS

Rational Number

Our model of the developmental sequence on which a deep and flexible understanding of rational numbers depends is formally identical to that for whole number. In the first phase (Level 1), we proposed that children develop two separate schemata; (1) a global, qualitative structure for proportional evaluation that is spatial and analogic, and that encodes one quantity in relation to another (Moss & Case, 1999; Resnick & Singer, 1993; Spinillo & Bryant, 1991); and (2) a numerical structure for splitting or doubling that is digital and sequential, and that includes the results of a number of familiar splitting operations (e.g., 2 × 50 = 100; 100/2 = 50; Case, 1985; Confrey, 1994; Kieren, 1992). Both of these schemata appear to be in place by about 9 to 10 years, and the latter depends on the availability of the central conceptual structure for whole number described earlier.

The new unit that is formed as these schemata are elaborated and integrated is the rational number line, a structure that permits children to solve a number of problems that involve ratio, rates, and/or equal sharing, provided that they involve simple halves or doubles. Once children understand a system for representing rational numbers (e.g., fractions or percents), they can gradually expand their understanding to include other forms of representation. Finally, after another period that is ...