![]()

1

The Perception of the Extended Stimulus

J. Gregor Fetterman

Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis

D. Alan Stubbs

University of Maine

David MacEwen

Mary Washington College

In a well-known passage, Stevens (1951) stated what he considered the "central problem" for all of psychology—the definition of the stimulus. Although Stevens' remarks appeared well after psychology became an independent discipline, the concept of the stimulus has always played a central role in psychology. Questions about the relation between stimuli and sensations were fundamental to early psychophysical research, and psychophysics figured prominently in establishing psychology as a separate discipline. Many important questions in perception, about space, form, and motion, are closely tied to views of the stimulus. Similarly, many of the basic issues in the area of learning—discrimination, generalization, stimulus equivalence, and so on—concern stimuli. And, newer developments in cognition, though often emphasizing mental structures and processes, also are concerned with the nature of stimuli (e.g., Rosch, 1975), and the relation of mental categories to environmental constraints (e.g., Shepard, 1984).

Experimental and theoretical analyses of stimuli constitute the sine qua non of stimulus control research (e.g., Mackintosh, 1977; Terrace 1966) in the area of learning. The title of this volume suggests that analyses of stimulus control have become increasingly cognitive, along with much of animal learning (e.g., Hulse, Fowler, & Honig, 1978). There are obvious reasons for an increased emphasis on cognitive factors. One is that there has been an infusion of theories, concepts, and methodologies from human cognitive research (see, for example, the chapters by Blough and by Cook in this book), which has fostered a science of comparative cognition (e.g., Roitblat, 1987; Wasserman, 1981). A second reason is the use of more complex stimuli—arrays of forms, patterns of stimuli, pictorial images, and the like—stimuli now easier to arrange and study due to computers and related advances in technology. These complex events seem more ecologically valid than the simple dimensions involving tones and lights of past research, and these events seem also to demand more "processing" from our subjects.

Although the cognitive framework has become more prevalent and the stimuli apparently have become more complex, we argue that the basic way in which stimuli are considered remains intact. A longstanding tradition in learning and much of psychology involves the categorization of environment and behavior into basic elemental units. This point of view, of course, has a long history in psychology and mental philosophy, going back to the mental atomism of the associationists, and, more recently, the behavioral atomism of Watson. This approach has been carried over into modern psychology and the area of stimulus control (e.g., see a recent review by Williams, 1987), including research involving complex and extended stimuli. Thus, in cases where the "stimulus" involves events extended over time (e.g., Dreyfus, this volume), over space (e.g., Sherry, this volume), or over time and space (e.g., Rilling, this volume), the traditional approach would treat these extended patterns as associated collections of punctate elements comprising the larger extended stimulus unit.

A second feature of this "elemental" view of stimuli concerns the hypothesized relation among the elemental constituents of the extended stimulus. Even simple stimuli are multifaceted, and the complex stimuli now widely used force us to consider how the different features of the whole are related. According to traditional views of such situations (e.g., Rescorla & Wagner, 1972; Sutherland & Mackintosh, 1971), the elemental features of complex stimulus events compete for limited associative strength so that control by one element or stimulus dimension is gained at the expense of others.

The elemental/analytic tradition is well ingrained in thinking about stimuli and behavior. It is commonly assumed that the perception of complex/extended events must involve a piecing together of more elemental events. This point of view naturally leads to questions about the nature of the basic elements, and about the underlying cognitive mechanisms that mediate stimulus control. And, because it is also assumed that multidimensional stimuli necessarily involve competition among dimensions, research is often aimed at identifying one dimension as the controlling dimension (e.g., Reynolds, 1961).

In this chapter, we consider an alternative approach rooted in the area of perception and based specifically on James Gibson's theory of perception (e.g., Gibson, 1979; see Rilling in this volume for a related point of view). From the standpoint of Gibson's perceptual approach, different features of a complex stimulus array need not be viewed as competitive elements, nor must a stimulus always be construed as discrete, momentary, or punctate (see also the chapter by Honig for a similar discussion). Instead, the functional stimulus may consist of patterns of change, relations among features, and so on—complex events whose invariant features are extracted from the flux comprised of seemingly more elemental events (Cutting, 1986).

Gibson’s Theory of Perception

Gibson's theory of direct perception is controversial (e.g., Ullman, 1980), but few would argue with the claim that Gibson revolutionized the concept of the stimulus for perception, and perhaps all of psychology (e.g., Gibson, 1960). Gibson's ideas have had an impact and provided a challenge to long-accepted views about stimuli and perception. We are concerned with Gibson's concept of the stimulus in particular because it constitutes a radical departure from the elementarist tradition, and because his approach provides a congenial framework for analyses of complex and extended stimuli.

Gibson proposed a new framework for perception in which the stimulus played a central role (e.g., Gibson, 1950, 1960, 1966). Traditional views held that the proximal stimulus for visual perception consisted of a mosaic of light intensities on the retina from which the distal properties of the world were recovered through a reconstruction of sensory elements into a unified perceptual whole. Perceptual experiments typically involved systematic manipulations of the putative elements in an attempt to reconstruct the percept from its constituents (e.g., Holway & Boring, 1941). Gibson recognized that the "received" view of the stimulus for visual perception was inadequate, and that the information available to an observer in motion was much richer than that available from the snapshot view of a static display, as had typically been used in experiments on visual perception. Gibson's key insight was the simple but deep observation that, whereas many changes in the pattern of stimulation occur at the receptor level as an organism moves, certain higher order patterns remain invariant and specify both permanent properties of the environment, and our changes with respect to the world. According to Gibson, these higher order invariants serve as the stimuli for the perception of many stable features of the environment, whereas the specific changes in specific stimuli provide cues to other aspects such as movements on the part of the observer.

The information about distance conveyed by a gradient of deformation (Gibson, 1950) provides a good example of a higher order "extended" stimulus. When he confronted the problem of how airplane pilots perceive distance, Gibson noted that the rate of change of a given point on the retinal image is inversely proportional to the distance of its distal source; that is, the change for nearby objects is greater than for distant objects. When we move forward one meter, for example, an object two meters away becomes one meter away and is 50% closer (with greater relative change), an object 10 meters away becomes 9 meters away (10% closer), and one 100 meters away becomes 99 meters away (1% closer). Continued forward motion involves continued change visually, but at the same time a persistent pattern of change for the objects of the world, with objects, 1, 10, and 100 meters away undergoing different relative amounts of change. Even as one travels down the road, seeing new views, there is an ongoing invariant structure in the higher order stimulus, though the specific elements of the scene change.

Gibson and Complex/Extended Stimuli

Simple Versus Complex Stimuli

First, consider the fundamental distinction between simple and complex stimuli from the Gibsonian perspective. How are recent studies of concept formation, relative numerosity discrimination, and so on more complex than prior research on hue or intensity discriminations? Perhaps it is the fact that the seemingly complex stimuli are not easily specified in terms of one single simple dimension, or that the stimulus can only be specified with a great deal of description, or at a fairly high level of abstraction. A photograph is said to be worth a thousand words, and the stimuli in discriminations involving sets of photographs are harder to describe than those involving red versus green.

Curiously, however, stimuli we have called simple might really be more complex and those we have called complex might be more simple. Stimuli such as a homogeneous red field, a pure tone, or a line drawing have often been used as stimuli and considered as elemental events. But, as Gibson pointed out, these stimuli are the exceptions, stimuli that are rarely encountered in everyday experience. Simple line drawings have been shown to people without prior experience with pictures with the result that people often are confused by these "simple" but ambiguous drawings. On the other hand, these same people are able to report accurately about seemingly more complex color photographs, stimuli more complex in their specification, yet more like the scenes they represent (Hagen, 1980).

In many cases it seems as though stimuli that appear complex from the experimenter's point of view may not be complex from the subject's point of view, and this might explain seemingly puzzling results from studies involving "complex stimuli." Research on concept learning using many different photographs (e.g., Wasserman & Bhatt, this volume) indicates that animals acquire the discrimination very rapidly: Concept discrimination does not appear to require a great deal more training than seemingly simpler discriminations of red versus green. Concepts based on nominally "simple" projective line drawings do, however, appear difficult for pigeons to learn (Cerella, 1977). Similarly, discriminations based on relative numerosity (Honig, this volume) are learned with impressive speed. And, spatial memory tasks, which also would seem quite complex, are acquired rapidly (e.g., Olton, 1979).

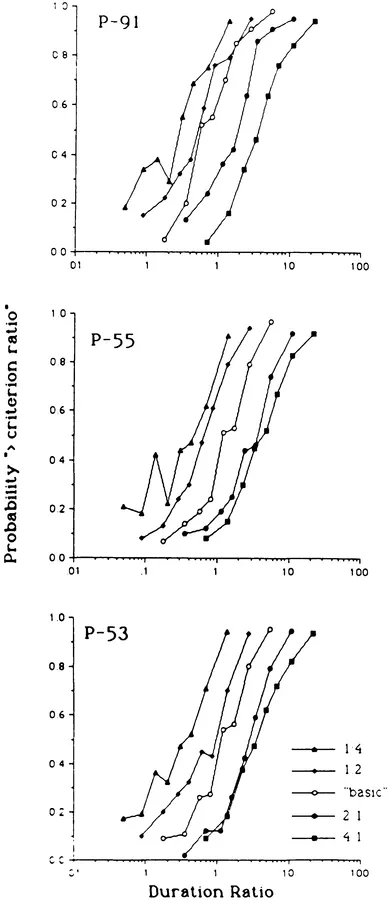

Consider, as a final illustration, an experiment by Fetterman, Dreyfus, and Stubbs (1989). They trained pigeons on a temporal discrimination task under which a red light of one duration (t1) was followed by a green light of another duration (t2), and then food was provided for different choice responses depending on the temporal relation between t1 and t2. In the "basic" condition, one choice was reinforced when t1 > t2, and the alternate choice was reinforced when t2 > t1; in other words, the birds were trained to identify the longer of two successive stimulus durations, with about 900 different combinations of the two durations intermixed over trials. In other conditions a seemingly more complex temporal comparison was used, one that required subjects to discriminate whether the ratio of the two durations (t1/t2) was less or greater than a specified criterion ratio. Under the 2:1 condition, for example, one choice was reinforced when the t1/t2 ratio was less than 2:1 (e.g., 9-s vs. 6-s), and the alternate choice was reinforced when that ratio was greater than 2:1 (e.g., 9-s vs. 3-s). Different criterion ratios were used (4:1,2:1, 1:2, 1:4), in addition to the basic task, which involved the "simpler" shorter–longer comparison.

Figure 1.1 displays a psychophysical summary of the results and shows the probability of choosing the alternative associated with duration ratios greater than the criterion ratio as a function of the ratio of the first to second duration. From left to right the curves represent performance under criterion ratios of red to green of 1:4, 1:2, 1:1 (basic), 2:1, and 4:1. The curves are orderly and ogival in form; more importantly, the slopes of the curves are similar, indicating that the accuracy of discrimination was comparable across conditions. Evidently, the various temporal discrimination tasks were similar from the bird's perspective; whether the discrimination involved a judgment that could be described in simple terms—"longer than"—or a judgment that required a more complex verbal description—"if red is more than twice the duration of green, etc."—the tasks evidently were comparable.

FIG. 1.1.Probability of responding to the key color associated with duration ratios greater than the criterion ratio as a function of the ratio of the first (red) to second (green) duration. Each set of connected points within a panel shows a different criterion ratio condition, and each panel represents the performance of a single pigeon.

Precise comparisons of simple and complex tasks is not without complication because both the s...