eBook - ePub

Pioneers in Peace Psychology

Doris K. Miller: A Special Issue of Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology

- 64 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Pioneers in Peace Psychology

Doris K. Miller: A Special Issue of Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology

About this book

First published in 2005. This is a Special Issue of Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, Volume 11, Number 4, 2005 focusing on Doris K. Miller. It includes works on her being an active psychologist, as being a pioneer of peace psychology and social responsibility as well as a personal account of her being a colleague and a friend.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pioneers in Peace Psychology by Richard V. Wagner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Pioneers in Peace Psychology: Doris K. Miller

Doris Miller was born in 1922, the youngest of four children. Her parents emigrated from Russia in 1905, settling in Paterson, New Jersey, the silk manufacturing center of the United States. Her father, knowing nothing about the business, ventured into silk manufacturing. Doris characterized him as courageous and adventurous. Because his values encompassed concern about workers, he was instrumental in inviting the Industrial Workers of the World into Paterson to organize textile workers. Doris’ mother was an advocate for the underdog—a colorful and fascinating woman who quietly and personally helped needy families in many ways. She was determined that her two daughters have educations equivalent to those of her sons. Using her maiden name to avoid embarrassing her children, Doris’ mother attended night school for adults and graduated with honors in biology and English grammar. Both parents were demanding of their children, all of whom graduated with honors from high school.

Doris entered Boston University where she majored in liberal arts, with a creative writing specialty. She became an editor of the medical school section of the university’s newspaper. As a sophomore, she was one of the college paper’s editors who unearthed financial malfeasance by University trustees who siphoned revenues from the bookstore. The trustees’ actions were reported in an unauthorized edition of the school newspaper distributed to public news kiosks. Unlike the other editors, all upper class men who were summarily expelled, Doris was given the option of transferring without prejudice. Cognizant that she had no power to contest this decision because “I was an undergraduate, an underclassman, and a woman,” she continued her education at the University of Wisconsin.

Her first direct experience with anti-Semitism occurred at Wisconsin when she was looking for student housing. Her maiden name, Koteen, signaled no special ethnicity, but when a potential landlady questioned her “origins,” she identified herself as Jewish. “From New York?” she was asked. She was told that she could room only in housing designated for Jewish students. Certain that administrators in this famously liberal university would not tolerate this bigotry:

I went to the Housing Department and raised hell about it. They knew about it and collaborated with it. I was very upset. This is what got me started in my Wisconsin activism. I joined the integrated housing movement led by a Black graduate student who was later arrested on a rigged “miscegenation violation.” I was less concerned about the Jewish students—we had a variety of ways to secure good housing.

At Wisconsin Doris majored in psychology. From 1942 to 1944 she worked in Harry Harlow’s laboratory, feeding and testing rhesus monkeys to record differences in their perception of form and color before and after lobotomy. These tasks from Harlow’s point of view were the equivalent of floor sweeping, and the only functions permitted to female students. Doris and one other woman were the first and only women permitted into his laboratory for a 2- or 3-year period. Later, he apparently surrendered some of his misogyny—attributed by its victims to a past unsuccessful marriage to a psychologist. His imperious and intimidating manner accounted for Doris committing her only research “fraud”: The monkeys’ test behavior was so consistently reliable that any deviation was noteworthy. On only three random days of several hundred, their test behavior was agitated and their responses aberrant. On those occasions, she recorded but withheld the actual responses, submitting to Harlow test performance outcomes consistent with their predictable ones. In what Doris identifies as her first independent scientific inquiry, she reviewed everything she could recall that might have made these occasions different, finally realizing that the only common denominator, shown in her daybook, was her menses, so irregular that no pattern of aberrant responses had been established. Not wanting to hand Harlow another reason to discriminate against women, she mailed him the actual test results only after receiving her bachelor’s degree in 1944, telling him in the cover letter her purpose for withholding the data.

While she was at the University of Wisconsin, Doris noted that psychology had little or nothing to do with the upheaval and protest occurring around issues of social justice: “There was no way in which I could integrate studying psychology with how I was living my life. It had no connection for me at the time.” Besides, she planned to go to medical school and did not intend to continue studying psychology.

She was involved on campus with efforts to achieve integrated housing, and beyond those walls, with anxiety about the United States entering World War II:

I hung around with groups of students who were deeply interested and disturbed with what was happening in Europe. I was not politically affiliated in any way. At that point. Hitler had marched beyond Poland. We knew something about Jews being exterminated, but we did not know that communists, gypsies, homosexuals, and other despised groups were sharing that fate. The newspapers were not reporting that as far as I can remember. That something was happening to the Jews was clear. That there was not a big hue and cry about it was clear. I was not a pacifist. I didn’t think in terms of just and unjust wars. I knew there was something awful happening with this madman overrunning Europe and something had to be done. It wasn’t until I got to graduate school that I became more politically informed and more impassioned about it.

During her senior year at Wisconsin, Doris married a soldier stationed on campus, who soon went overseas. When he returned in 1946 after their 2-year separation, they tried for a year to make the relationship work, but “We hadn’t really known each other when we married … we were too young.”

This article draws on data from an interview with Susan McKay that took place in Washington, DC, on January 14, 1995. The interview traces her life-long involvement with social causes. Doris shows us how the early roots of her activism were fostered by strong family values. She is among the remarkable women of her generation who defied traditional gender roles to speak out passionately, engaged her sharp intellect, and demonstrated the courage to act upon her beliefs. This article illustrates the chronology of her commitment to act and speak out for social justice.

EARLY CAREER

Doris’ first job for the summer following her bachelor’s degree was suggested by Norman Cameron, her clinical psychology professor whom she described as “well-known and wise.” Because he thought she was a gifted clinician, he recommended her for a summer job at a children’s residential treatment center. She expected to be in charge of the girls’ waterfront and doing “something else, too.” When she found out that they wanted her to be a counselor in the craft and recreation department:

I didn’t know copper from silver, and in three minutes I made up a program for teaching current events and creative writing to be used for diagnostic purposes … as an alternative to the recreation assignment. They loved it. The principal put together a classroom with 25 kids, 10- to 18-years-old, with IQs ranging from about 100 to 200. Boys and girls diagnosed from sociopath to schizophrenic. I was 21 years old when I was confronted with this. We were to meet daily for two hours in a classroom with no air-conditioning. It was an enormous challenge, but I learned an enormous amount from the kids. Other things I learned there shaped some of my future education and training.

She was most impressed with the social workers’ skills in interviewing and relating to the children, and questioned the staff psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers about their respective professional training. This miniresearch prompted her to apply to the Simmons School of Social Work in Boston where she was accepted for the following fall semester. The summer’s work, therefore, moved her into an entirely unexpected career trajectory. She completed her coursework for her master’s of science in psychiatric social work in 1946, getting her degree in 1947 upon completion of her thesis. “The social adjustments of the first 38 lobotomy patients at the Boston Psychopathic Hospital.”

THE UNITED PUBLIC WORKERS’ UNION: “THE MOST SEMINAL TRAINING OF MY LIFE”

After her graduation from Simmons and a year’s work at a social agency in New York, Doris was employed at the Veterans Administration (VA) New York regional office, housing the largest mental hygiene clinic in the world. The size was important because many psychologists who had served in World War II were now interning at this office while they wrote their dissertations. Doris joined the United Public Workers union immediately and quickly became active. This union was considered “red,” as was any union militantly fighting racism. Union coworkers included not only professionals but semiliterates in menial jobs and bright people with limited education—groups with whom she had not previously experienced continuing relationships. She worked with them, ate with them, and went to church with them. The union was an authentic democracy, deeply formative for her beyond any other training she had.

Very quickly, I became an officer. This was 1947, with Senator Joseph McCarthy riding high. It was eye opening—the most seminal training in my life, more important than my psychology training. I think that the trade union experience promoted the usefulness of my psychology training. It taught me a way of thinking that I could use in psychology. It taught me about what happens in periods of domestic political terror as the McCarthy days were. I felt that I was freer than any co-workers to do exactly what my conscience told me. I had no dependents to support. The men and women with whom I worked did. They were good people, but they were scared to death. Federal employees could be summarily dismissed more easily than private sector workers. For example, during Congressional Committee investigations, federal workers had the “right” to take the fifth amendment, but could be fired fordoing so. So, many of my co-workers supported what the union stood for but were unable to put themselves in public-spokesman roles. That did not cause me to think less well of them; I understood the human circumstances.

At one point, I had sympathetic psychiatrists contribute money “to keep their names off the union list.” We needed money to defend the international head of the union who had been charged with contempt of Congress for not producing union membership lists.

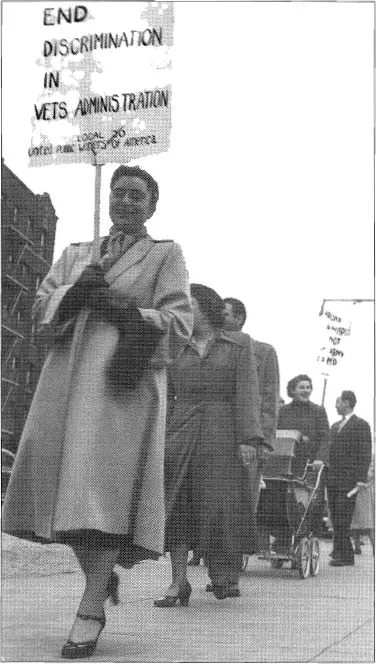

I was always very much involved in the fight against discrimination. Our union’s number one concern was eliminating racism—especially outrageous in the post World War II VA. I have a photograph that I prize more than any other, leading a picket line in front of a VA installation. On picket lines, I always wore high-heels, gloves, and was meticulously dressed. I didn’t fit anyone’s stereotype of an anarchist. These were the first professionals to picket in a federal agency.

Psychologist Carmi Harari was also working at the VA at the time and carried a picket sign reading “Nothing is too good for the veteran, and that is exactly what he will get.” Doris and others in the union were advising vets that their records at the VA were not confidential as promised and that these could be requested by the Federal Bureau of Investigation—for example, if a veteran applied for a post office job. The intent was to find out if the person might be a troublemaker for the federal government. Doris urged that people who sought help were entitled to security, advocating that therapists not record sensitive client information. She and her colleagues protested the release of client records that were to be used for this purpose.

Doris, as a union representative, testified in the U.S. Senate several times on the VA budget. Democratic Senator Joseph C. O’Mahoney, from Wyoming, headed the committee with oversight of the VA budget.

Doris K. Miller leading 1949 picket line.

Senator O’Mahoney was a very distinguished man. I think he had a background in the humanities. He wore a little string tie, spoke elegant English. He was the most literate member of Congress I have ever met, very courtly. He would say, “Ha, Miss Miller, you are a representative of the AFL or is it the CIO?” I said. “The CIO United Public Workers.” The second time I came back, he recognized me [and] said. “Ha, Miss Miller, good to see you again. What do you have to tell us this time?” The next time we went down we had been kicked out of the CIO along with the Fur Workers Union, the Steel Workers Union [and others] that were expelled during the period of McCarthy, presumably as “red” unions. The Senator began to ask about union affiliation. I said, “Sir, you are so well-informed, I am sure you know that we are no longer part of the CIO. We are the independent United Public Workers Union.” He asked, “Well, what was that about?” “May I set aside my prepared testimony and tell you?” I asked. He made the error of saying “Yes.” “Our union has been trying to integrate unions in the South. One of our organizers was killed for that. Our veterans fought WWII to eliminate racism.” On another occasion, the head of the VA, General Grey, had ordered 5,000 health workers fired, although funds ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- The Active Psychologist: Doris K. Miller

- Pioneers in Peace Psychology: Doris K. Miller

- Being a Pioneer: How Many Ways and How Many Days?

- My Colleague and Friend, Doris K. Miller

- Doris K. Miller and Psychologists for Social Responsibility

- Peace Activism and Courage

- SPECIAL ESSAY

- REVIEWS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INDEX