- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Children and Society

About this book

Provides a comprehensive overview of the issues, research and debates relating to children and the experience of childhood in late twentieth century Britain. This volume will address key issues such as juvenile crime, poverty, child protection and children's rights and their implications for the development of policy and services for children. Presents first hand accounts from children and parents.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Children and Society by Malcolm Hill,Kay Tisdall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Movements in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Children’s lives in social context

Children are just the same as adults, just younger and smaller.

(Girl aged ten, quoted in Childhood Matters, National Commission of Inquiry into the Prevention of Child Abuse, 1996)

Introduction

This book attempts to place children's lives in the UK today within the contexts of their personal social relationships and of the role of society at large, through its social policies. The interests, feelings, behaviour and personalities of individual children are crucially affected by, and in turn affect, their key relationships — with parents, other family members, peers, teachers and other professionals, and wider society. Furthermore, the experiences of individual children are part of the set of relations between children in general and adults, which shape expectations about the appropriate and acceptable nature of childhood within society and in particular communities. Increasingly it has been recognised that children are not simply passive recipients of adults' models, knowledge and values, but contribute actively to the creation of the social worlds in which they live, both individually and collectively.

Present-day Britain offers a wealth of opportunities, but also challenges and constraints, for children. On the one hand, material standards of living, life expectancy and health have, on average, reached unprecedented levels. Technological developments ranging from the aeroplane to CD-Roms can potentially link children to experiences, cultures and environments across the world. Yet, as we shall see, many children live in situations of material and social deprivation; some are physically or sexually abused. The modern or indeed post-modern world has brought new or increased hazards, such as motor accidents, drug misuse and AIDS.

Demographic changes also impinge on children. Since the 1960s a number of trends have occurred in the UK and indeed in most other countries of Western Europe (Kiernan and Wicks 1990; Richards 1995; Tisdall with Donnaghie 1995):*

- fertility and average family size have fallen

- children form a smaller proportion of the population

- the proportion of births to unmarried mothers has grown substantially (although many such births are jointly registered, suggesting cohabitation by the parents)

- the number of households headed by a lone parent has grown (about 90 per cent by lone mothers)

- approximately one in three marriages ends in divorce

- the numbers of remarriages and reconstituted families have increased

- ethnic diversity has increased, though today the great majority of children of ethnic minority background were born in the UK

- male unemployment has increased markedly

- there has been a substantial rise in the proportion of mothers in paid employment, though many are in part-time work.

Consequently, few children are now raised in what used to be called a conventional family household comprising a married couple and their joint children, with the father working and the wife at home, although this does still apply to some children for part of their childhood.

The diversification of households and families has implications not only for the immediate context of children's lives, but for their aspirations and transitions to adulthood. The so-called traditional goals of adulthood — full-time employment, marriage with children, forming an independent household — are not achieved by all young people today and may not even be the goals of some (Jones and Wallace 1992; Tisdall 1994; Coles 1995). Many children do aspire to work, money, home ownership and marriage, but they also see growing up as associated with freedoms, making decisions, assuming responsibilities, and coping with pressures and obligations (Lindon 1996).

The 1990s have been a time for adults to re-examine their perceptions of children and attitudes towards them. Academically, traditional approaches to childhood and the very notion of child development have been questioned. In law and policy, increased prominence has been given to children's rights and especially to their entitlement to influence decisions affecting themselves. So far, this has chiefly meant greater sensitivity to hearing and understanding the viewpoints of individual children. There has been little preparedness to confer a greater role for children as a social group to influence policy and practice in schools, local neighbourhoods and society.

The social connectedness of children's lives and development is the overarching theme of this book. Within that perspective we shall address some of the core private and public issues concerning children, with a focus on the following:

- How is childhood defined and 'socially constructed', particularly by academic commentators and service providers, or within policy formulations?

- What kinds of children's rights are recognised?

- What kinds of children's needs are identified?

In this chapter, we discuss the social contexts of children's experiences and differing conceptions of childhood. Children's rights and needs will be explored in the two following chapters. The rest of the book will examine particular aspects of children's lives, with each giving special attention to these recurrent themes. The aspects covered are:

- family relationships

- friendships and peer relations

- poverty and access to resources

- schooling

- health

- crime

- child abuse and protection

- separation from one or both parents.

Special emphasis is given to children's own perspectives and to the position of disadvantaged children.

In any discussion of children and childhood, an implicit or explicit choice has to be made about where to set the upper age limit. The boundaries between childhood and adulthood in modern Britain are multiple and indeterminate, with the teen years constituting a broad period of transition. Legal thresholds recognise different ages at which young people are entitled to partake in 'adult' activities, such as paid employment, sexual intercourse, marriage, driving and voting. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (see Appendix) defines a child as any person below the age of 18, unless majority is attained earlier under the applicable law (Article 1). Broadly we shall abide by this definition, whilst recognising that many young people do not regard themselves as children — partly because of the connotations of lower status and power than adults, which will be a leitmotiv of this book.

Children are of course a highly differentiated group of people. Age, gender, ethnicity, class, disability and other characteristics crucially affect children's experiences, self-perceptions and treatment by others. Social attitudes about these qualities often form the basis for marginalisation and stigmatisation, so that in this book we have attempted to integrate material which takes account of difference, rather than have segregated sections.

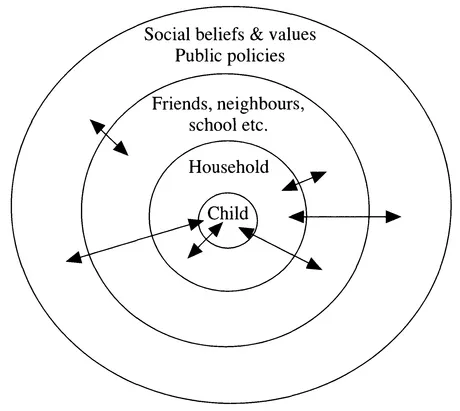

The main theme of this chapter is that children's physical, intellectual and recreational activities, as they evolve over time, are greatly affected by the attitudes, ideas and expectations of both the immediate and wider social context. Biology certainly plays a part in general patterns as infants grow into a post-pubertal young people, while genetic endowment affects differences between individuals (Rutter and Rutter 1993). Yet children's experiences are also intimately affected by conceptions of childhood which prevail in particular households, communities and societies. These conceptions are firmly located in social structures and in cultural and historical contexts which construct their meaning and significance (Jenks 1996). Firstly, we examine the concentric circles of influence with which children interact. Then we outline some differing definitions and views of children embodied in psychological and sociological thinking, before concluding with evidence about the varied ways in which child—adult relations have been manifest in different times and cultures.

The social connectedness of children’s lives and development

Children — and adults — have individual wants, needs, rights and interests, but they are also intensely social in their orientations. From early babyhood, children are highly dependent on and responsive to the caregiving and interactions of others, notably parents. Indeed, infants appear to have an innate predisposition to form attachments, which are usually formed with several adults and children, to varying degrees, within the first year of life (Schaffer and Emerson 1964; Smith 1979; Howe 1996). Babies in the first few months show an interest in other babies and will smile and vocalise with a strange infant (Becker 1977; Tizard 1986). From their earliest days, children are linked into a set of informal relationships —a personal social network which evolves over the life span. A child's personality, interests and activities are neither attributes of an isolated individual nor imposed by the environment, but are firmly located in the interactions between a child and the network or system of social relationships to which each child belongs. In complex and urban societies, people's time, activities and identities are only partly rooted in their local communities, since usually their personal and formal relationships link them in various directions and connect them with a number of different places. The network provides not only an immediate context for a child's activities and development, but also a range of conduits to social resources and supports and to societal institutions, values and policies (see, for example, Bronfenbrenner 1979; Dunst et al. 1988; Boushel and Lebacq 1992).

Figure 1.1 Children's social networks

Early network members tend to be 'inherited' from a child's immediate family or household, but soon the child's own temperament and choices, as well as external opportunities and events, influence the nature and quality of network relationships. These provide both significant influences and options in a two-way process of interaction. In other words, key social relationships are both active and reciprocal: socialisation is not usually imposed on a child but emerges through a process of mutual adaptation (Waksler 1991). Of course, power relations between adults and children greatly affect the scope for children to modify or resist social influences. The actions and sanctions used by adults to instil their expectations may be intended or experienced as authoritarian.

Children's networks vary greatly in their size, structure, composition and functions (Mitchell 1969; Cochran et al. 1990). Some children are immersed in a large system of relationships: others have few significant contacts outside the household. However, research indicates that it is the qualities of care, support and stimulation present or lacking in networks which are crucial, and not their size (Belle 1989; Savin-Williams and Berndt 1990). Network members can help children practically, emotionally, cognitively and socially. Relatives, friends and others contribute to the care and education of children, providing access to a range of experiences and ways of life besides those of the child's parents. A developing sense of identity is crucially affected not only by identification with and reaction against parents or carers, but also by a sense of belonging to or association with wider social groupings, which may be based on proximity, ethnicity, religion, language or life-stage, for example. Less positively, networks can be the locus of conflict, pressure and discriminatory behaviour (for example, towards children who look or behave differently from most others). Close-knit networks tend to offer greater intimacy and support than looser networks but also more pressure to conform.

For most children the key relationships are mainly with close relatives and other children of similar age. Non-related people of a different age can have particular significance, especially as children grow older (Galbo 1986; Belle 1989). Some cultures and some children are mainly family-oriented, whilst for others peers and friends are more salient. Ethnic minority families tend to retain strong ties with a wide set of extended kin, though migration has sometimes reduced or disrupted contact (Modood et al. 1994). Sometimes children's relations with adults and with peers are portrayed as antagonistic, but in fact they are usually complementary, each providing opportunities for distinct kinds of communication and learning about the world, for example (Corsaro 1992). Peer relationships offer opportunities for children to acquire different kinds of knowledge compared with, say, parents or teachers. For example, children's school progress and formal use of language appear to be enhanced by high levels of active involvement with adults, but the adaptability of speech for use in varied contexts can be helped by interaction with a larger number of peers (Cochran et al. 1990; Salzinger 1990). Likewise it is usually valuable for young people to have both adults and friends to confide in, often about different kinds of issues (Coleman and Hendry 1990). These matters are explored further in chapters 4 and 5.

Children, society, the state and social policy

Children's lives and relationships are from the very beginning affected by resources, policies and attitudes beyond their immediate network and neighbourhood. For example, the quality of early care will be affected by such factors as:

- parental income

- entitlements to child benefit and other financial assistance

- access to ante-natal care

- advice from midwives and health visitors

- the quality of housing and the local environment

- availability of early years facilities (playgroups, nursery centres etc.).

These are all affected by the economy and by government policies.

Children's knowledge about the society in which they live ranges from 'very well informed' to 'relatively ignorant' (Furnham and Stacey 1991: 191). Younger children are often very well informed about their immediate environment (Matthews 1992), but their notions about the functions and connections of different social and economic institutions, including central and local government, tend to be hazy until the teen years (Furth 1980). Understanding of particular public services tends to be greater than of national political issues and processes (Furnham and Gunter 1989).

In political theory and practice, children have typically not been considered at all or conceived of as dependent on parents (O'Neill 1995). The UK has not had an explicit and comprehensive children's policy. Unlike countries like Norway, Britain has no separate ministry which deals partly or wholly with children's affairs (Leira 1993). Rather, there have been specific policies directed at particular issues concerning children, notably education. Since 1948 several Children Acts (and in the 1960s Children and Young Persons Acts) have been passed, but these have been largely concerned with children who break the law or are thought to need special care or protection. The Children Act 1989, Children (Scotland) Act 1995 and Children (Northern Ireland) Order 1995 broke new ground in integrating early years provision (day care) and more general parent—child relationships, especially those associated with divorce. Whilst these developments have been largely regarded as positive, they have occurred against a background of low government priority to social issues or inequalities, not just in Britain but internationally (Packman and Jordan 1991; O'Neill 1994; Tisdall 1996).

The role of the state with respect to financial payments and service provision with respect to children and families is discussed in several later chapters, so here we simply foreshadow key elements. The actual policies pursued by governments and commentaries thereon have been affected by both general predispositions as regards the state and specific orientations with respect to parents and children. Within Western Europe, it has been common to identify three main approaches to the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Children's lives in social context

- Chapter 2 Children's rights

- Chapter 3 Children's needs

- Chapter 4 Children's family relationships

- Chapter 5 Children's peer relationships, activities and cultures

- Chapter 6 The schooling of children

- Chapter 7 Children and health

- Chapter 8 An adequate standard of living

- Chapter 9 Children who commit crimes

- Chapter 10 Child abuse and child protection

- Chapter 11 Separated children

- Chapter 12 Children's lives: re-evaluating concepts and policies

- References

- Appendix I

- Index