![]()

I | ENERGETIC AND STRUCTURAL ASPECTS OF EMOTION |

![]()

1 | Emotional Expression and Temperature Modulation |

Robert B. Zajonc

University of Michigan

The contributions of Nico Frijda to the study of emotions are so broad and they cover so many aspects that there is little to add. After having looked at the writings of Frijda on the subject, one is convinced that all the important things have already been said by him. It is therefore both a great honor to be associated with this event that honors his work and at the same time a challenge. For on this occasion one needs to say things that at least approach in depth of insight those things that he has discovered, conceptualized, clarified, and integrated. One is proud and humbled at the same time.

I wish to begin this chapter with one of those insightful Frijda thoughts. In his volume, The Emotions, Frijda had something very important to say about behaviors that are usually called “expressive.” They are those that are

evoked by events that an observer, or the subject, understands as aversive or desirable or exciting. They serve no obvious purpose in the same sense that instrumental and consummatory behaviors do. They are called “expressive” because they make the observer attribute emotional states to the person or animal concerned. They do so even when no eliciting event can be perceived by the observer. They make a mother look for the undone safety pin in the baby’s diaper, or cause a child to be frightened of the dog someone else is frightened of. (1986, p. 9)

There is a great deal of insight indeed in this short quotation—insight and wisdom. For this brief thought alone incorporates almost all of the most important aspects of the theory of emotions. It does so by what it does not assert. For it does not assert that expressions are the manifestations of internal subjective states, and very carefully does not assert or imply that they are the effects of autonomic processes. It does not assert that they are voluntary or involuntary communicative acts. But it does very clearly begin the story by focusing on the fact that their quality of being “expressive” lies in the ability of the observer, and even the “expressor,” of attributing to them a connection to internal emotional states. There is an enormous difference between saying that the so-called expressive behaviors manifest internal states and saying that they can be used by observers to make inferences about these states. There are only indirect grounds to justify any of these assertions that some scholars take for granted.

The second very important insight in the short paragraph makes expressive behavior part of an important social process. An expression may “make (italics added) a mother look for the undone safety pin,” Frijda said. Later (p. 11) he said that “‘expressive’ movements produce actual effects in the interaction with environment” (italics added). “Expressive behavior is behavior that establishes, weakens or breaks, some form of contact with some aspect of the environment” (p. 13). These statements assert, without making any prior decisions about the origin of expressions, that they have true and significant social effects. Frijda’s view makes emotions inevitably social phenomena that are to be treated with the concepts of social psychology.

This short, deceptively simple and innocent introduction to Frijda’s volume in The Emotions presented us with insights that changed the study of emotions. We will never be able to think of these phenomena as isolated neural programs underlying distinct emotional categories. We have looked for these programs for 100 years and Frijda is telling us that we have little chance of finding them. We must now look at the emotions as rich aspects of social lives—aspects that implicate almost all psychological phenomena. For we can find a significant participation of emotional elements in psychological processes ranging from classical conditioning to social conformity, from memory to collective representations.

In this chapter I concentrate on the expressive aspects of emotions, taking as my point of departure Frijda’s very careful definition of expressions as behaviors that might allow an observer or the participant to infer the presence of emotional states.

PREEMPTIVE CONCEPTS IN THE STUDY OF THE EMOTIONS

It is very important to be careful about the term expression of emotion, as Frijda was, because expression is one of those preemptive terms that provide us with a ready-made theory or explanation before all the facts are in, and often before any facts are in. These preemptive terms taken from everyday language will make us look at a phenomenon with a great deal of prejudice. There are quite a few such preemptive terms in psychology. Take the term retrieval. It implies that there must be a “store,” that there must be a “search” through that store, that the store holds intact distinct items, that there is a way of “locating” the item being searched, that this item remains unchanged and stable in the course of the search, and that it is somehow brought into consciousness as a communicable and intelligible response. There is hardly any evidence for these strong assumptions.

Expression is such a preemptive term, as well, and it has been with us for centuries. We have taken its meaning for granted, and Darwin used it taking it for granted that there is something internal that is being manifested by expression. The meaning attributed to expression by Gratiolet (1865) and Piderit (1867) made less claim about it representing internal states, for it was more closely tied to the sensory system. Thus, for example, the protrusion of the lower lip in disgust was considered by Gratiolet as a simple generalization of the instinctive instrumental reaction emerging when an unsavory substance enters the mouth—a reaction designed to expel the substance. To Gratiolet, the lower lip protrusion upon hearing an absurd idea was not a manifestation that an intellectual examination has terminated in a feeling of contempt for what was presented, but an instinctive gesture of disgust seeking to expel the idea from one’s consciousness as one expels a rotten oyster. From Darwin on there was a theory embodied in the word “expression.” It meant (a) that there is a distinct internal state for each emotion, (b) that this distinct state seeks externalization of a distinct form, (c) that there is a one-to-one correspondence between the internal state and its outward manifestation, (d) that there is to be found a “triggering” neural process that can connect the internal state to its externalized output, and (e) that the internal process has sufficient energy directed toward its own externalization, but that under some circumstances it can be “suppressed” by a process requiring even greater energy.

That is quite a bit of meaning and theory to be contained in one word. I call expression a preemptive term because it preempts a theory yet to be developed. In the case of the emotions, there is yet to be solid evidence about any of the above five points about the emotions when we speak of their “expression.” It is indeed quite difficult to resist the temptation to use the term expression in its rich meaning. So much more immediately comes to mind. But very little of it is confirmed or known. Clearly, Frijda was well aware of this temptation and he took great care in his explication of the emotional processes and their expressive correlates in his work.

An important fact that complicates our understanding of the emotions and that was recognized explicitly by Frijda (1986), is that the correlation between the so-called expressive movements and internal subjective states or their autonomic correlates is very unstable and quite low (Stemmler, 1989; Wenger & Cullen, 1958; Zajonc & McIntosh, 1992). There are internal states that do not manifest themselves externally either in motor behavior or in autonomic activity. Equally, there are emotion-like external movements that have no underlying internal correlates. You say CHEESE and you look like you are happy. But it is only an utterance. Or is it? We shall see that there is in fact more than just the utterance.

For these reasons, I chose in my own work (Zajonc, 1985) to replace expression with the clumsier but more neutral term emotional efference. If we for a moment avoid using the term emotional expression and substitute for it emotional efference, we can ask some new and interesting questions. For example, we asked questions about the consequences of emotional efference, examining instances where there was what “looked like” an emotional efference but being fairly sure that no detectable underlying emotional process accompanied this efference. If such instances exist, and common sense as well as the empirical data suggest that they do, then perhaps emotional efference functions not only to externalize internal emotional states and communicate them to others, but it has other functions as well. Its evolutionary provenance may not be found fully it its communicative value (Andrew, 1963) but in another function. In all fairness, it must be acknowledged that Darwin himself did not insist that expressive movements were selected primarily for their expressive purpose. No muscle, he said, “has been developed or even modified exclusively for the sake of expression” (1965, p. 354).

In the rest of this chapter I also use the term emotional efference instead of emotional expression.

IS THERE A PRIMARY FUNCTION FOR EMOTIONAL EFFERENCE?

If emotional efference has functions other than expressive or communicative, what are they?

Waynbaum’s Vascular Theory of the Emotions

The answer to this question is supplied by an obscure French physician, Israel Waynbaum (1906, 1907a). Waynbaum had no laboratory, no academic appointment, no connection with psychologists. He was an amateur scientist in the true sense of the word. All this was when science was more a hobby than a legitimate pursuit institutionalized by such supportive organizations as the National Science Foundation in the United States or CNRS in France. But he was extremely well read and had fabulous insight. Waynbaum rejected the idea that emotional efference had primarily or even mainly a communicative purpose. He attributed to it an entirely different function. He offered instead the revolutionary hypothesis that facial gestures, in general, and emotional gestures in particular, have first of all regulatory and restorative functions for the vascular system of the head.

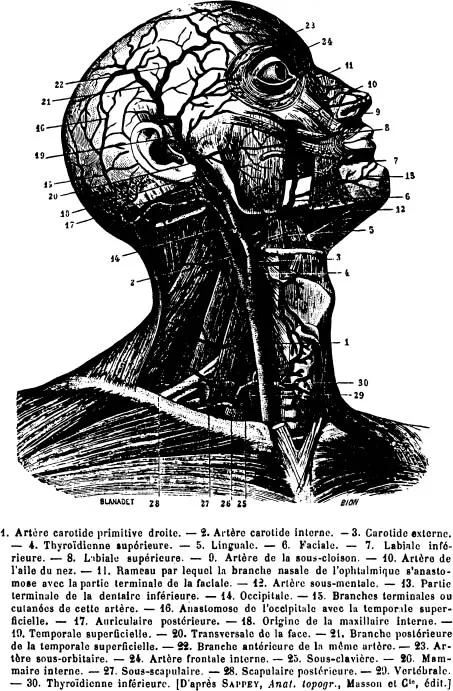

The main clue for Waynbaum’s hypothesis was the curious organization of the vascular system supplying blood to the head. He observed that the brain—the most crucial organ of the organism, which has undisputed priority in receiving scarce support in all domains—is not supplied by blood directly and independently. Rather, the main carotid artery is divided at the neck into two branches: the internal, which supplies the brain, and the external, which supplies the face and skull (Fig. 1.1).

It was this configuration that spurred Waynbaum to look for a connection between facial gestures and their effects on blood supply to the brain. Because blood supply to the brain must remain at a fairly constant level—it can neither be much reduced nor increased—why wasn’t the brain supplied independently and directly? Why was it sharing its supply with the face and skull? Waynbaum thought that the branching in the main carotid artery must be there to act as a regulator. But how? And what had all this to do with emotional efference?

First, Waynbaum observed that all emotional experiences produce disequilibria in the vascular processes. For example, in the case of fear, blood is redistributed to supply skeletal muscles to meet the demands of an incipient response, say a sudden flight. It is therefore less available for other functions. If there was a branching of the supply close to the brain, adjustments could readily be accomplished; if the brain suddenly needed blood, it would receive it at the cost of the supply to face and skull, which are less critically dependent on blood supply. Thus, Waynbaum conjectured that this vascular architecture exists to allow the facial branch of the main carotid artery to act as a safety valve.

How could this work? The muscles of the face can press facial arteries against facial bones and thus shunt blood away from the brain when there is an oversupply. They can equally relax and allow greater inflow when there is not enough. Waynbaum thought of the facial muscles as tourniquets that could constrict the diameter of the facial arteries and hence reduce uptake of blood in these regions, or allow freer flow when open.

And what has all this to do with the emotions? Waynbaum was quick to relate blood flow to hedonics. He offered the interesting conjecture that brain hyperaemia, within certain limits, is pleasurable, whereas anemia is experienced as a negative subjective state. A sudden lack of inflow feels bad, more as a discomfort that seeks restoration of a previous state. Therefore, resumption of ample flow feels good by contrast.

Freeing himself from the semantic network in which the term expression was embedded, Waynbaum was able to look at emotions not as ending with the motor externalization of the internal state, but was able to think of the possibility that facial efference was itself capable of producing subsequent events, that is, subjectively felt hedonic consequences. So, like James (1884), Waynbaum contradicted the common notions about the order of the emotional sequence, but unlike James, he proposed a specific process that would explicate such a sequence.

FIG. 1.1. The vascular system of the head. Note the branching of the main carotid artery (1) into internal that supplies the brain (2), and external that supplies face and skull. (From Waynbaum, 1907a).

Waynbaum’s ideas were so implausible at that time that when he presented them at the Académie he was summarily dismissed by Dumas (1906) and Piéron (1906). Neither found the idea to have any merit. Piéron took Waynbaum to task for offering a “finalist” explanation of facial expressions, asserting that it is quite dangerous to explain physiological processes by their alleged usefulness. He addressed the Académie in uncertain terms: “Je crains, d’une manière générate, outre des difficultés physiologique et anatomiques très sérieuses qui s’opposent à l’adoption de cette thèse, que M. Waynbaum n’ait abusé du principe d’utilité” (p. 475). Given the stature of these scholars against Waynbaum’s modest credentials, Waynbaum’s career was essentially finished at the point of that meeting. And he published only one other paper in 1907, which must have already been in press at the time of the meeting (Waynbaum, 1907b). Dumas, who later (1933) wrote the definitive psychology text, devoting three chapters to emotion, did not mention Waynbaum at all. And Waynbaum’s work remained uncited between 1907 and 1985.

Blood Flow versus Brain Temperature

Pieron and Dumas did not touch on most of Waynbaum’s misconceptions and false assumptions. ...