![]()

1

Selection

Learning about remote buildings through media

Photographing the Taj Mahal

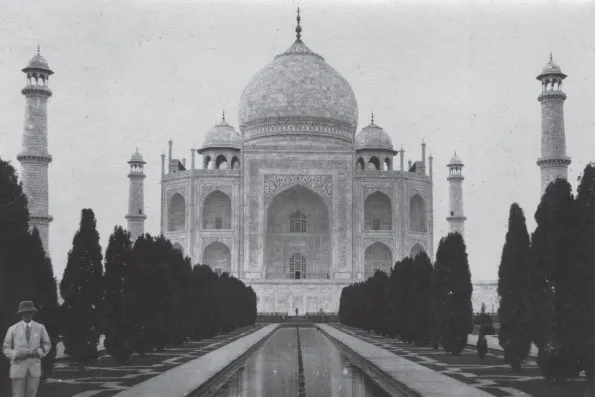

If we conduct an image search using an online search engine and the search term “Taj Mahal,” the search will result in several images, many of which appear to be taken from the same direction or point of view. Given a collection of images generated through such a search, there is an apparent preference among photographers for a viewing position at a point south of the mausoleum—viewing the building northward along the length of the reflecting pool. An image such as the one shown in Figure 1.1 is typical of the results received in such a search.

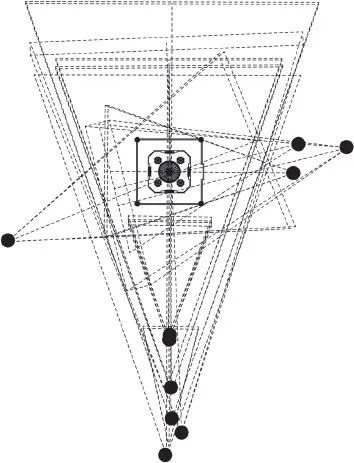

Of the first ten images returned in a sample search I conducted in late 2014, six of the images are taken from similar points of view, as illustrated in the map in Figure 1.2, recording the photographers’ positions, fields of view, and directions of view, relative to the position of the Taj Mahal at the center of the map.1 Additional images can be cataloged and mapped in this way, but the overall pattern of the viewpoints’ spatial distribution tends to hold constant even as the search is expanded to include additional images. While online image searches for “Taj Mahal” are likely to return a handful of images from other points of view, photographing the mausoleum from the south is—at least within collections of images gathered through online image searches—inarguably the most popular view of the Taj Mahal.2

1.1

The Taj Mahal as photographed in 1924 by Wilbur A. Sawyer.

Credit: Wilbur A. Sawyer, photographer. (This item is in the public domain.)

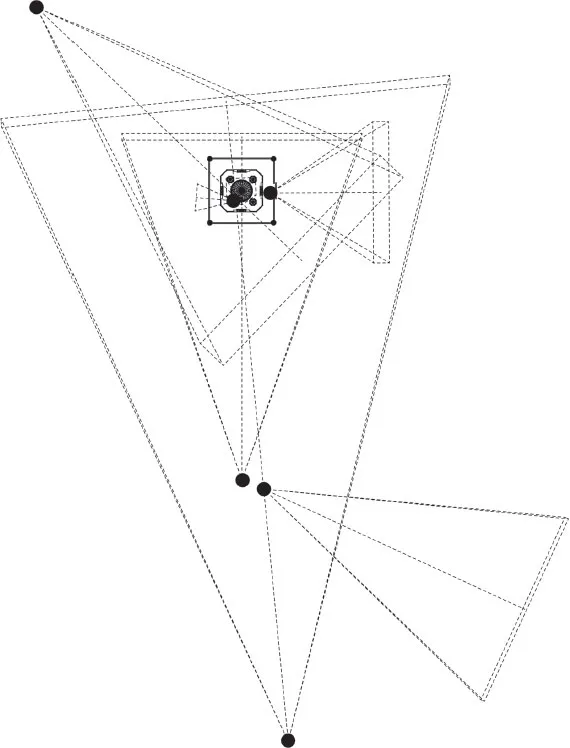

If we consider a different collection of images of the Taj Mahal, such as a collection of images produced by a single photographer over the course of a single visit, or an edited collection of photographs appearing in a book or scholarly article, common sense will suggest that the distribution of viewpoints should vary—a single photographer is much more likely to wander the site than to take multiple photographs from a single point, as a scholarly approach to photography is likely to consist of carefully selected images chosen to bolster an argument. And as we drew a map of the points of view resulting from an online image search, we can draw a map for an edited collection of photographs—for example, a set of images of the Taj Mahal appearing in a scholarly article written by renowned art historian Ebba Koch and published in 2005.3 Figure 1.3 is a map of the photographs of the Taj Mahal in Koch’s article.

The map of Koch’s photographs, reproduced at the same scale as the map of the online-searched images, indicates a dispersed collection of images. Koch’s are not the casual photographs of a tourist, but are instead deliberately framed and selected photographs—many of them taken by Koch herself on multiple visits to the site over a period of several years. A comparison of the two maps (Figures 1.2 and 1.3) suggests differences between, on one hand, a collection of photographs compiled from the aggregated work of several casual photographers, and, on the other hand, a collection of photographs carefully selected and structured to support a scholarly argument. By mapping where photographers stand when they take pictures, we can make inferences about the practices of people who visit the building, such as the apparent tendency of casual visitors or tourists to repeat the performance of prior visitors by taking their own version of a photograph they’ve seen before.4

1.2

Map of online images of the Taj Mahal showing photographers’ positions, fields of view, and directions of view.

But how does this comparison of practices inform us about the Taj Mahal as a built structure? Surely in both cases discussed here—the tourist images and the set of images selected for scholarly purposes—the same building is being photographed; it doesn’t seem that either map communicates any new information about the building’s physical form, its material, its ornament, or its structure. Is our understanding of the building as a building affected by knowing how people choose to depict or represent it? That is precisely the question at the root of this chapter—and it is a central question of the book. As architectural historian Beatriz Colomina has succinctly acknowledged, every building is “not simply represented in images but is a mechanism for producing images.”5 Buildings, in this view, are something more than assemblages of physical material in specific places: they are parts of a system for producing, disseminating, and receiving information—in short, the system of architecture.

1.3

Map of Ebba Koch’s images of the Taj Mahal.

What is architecture?

Buildings—such as the Taj Mahal, or Lincoln Cathedral, or a bicycle shed6—are all architecture, yet the word architecture, in my view, refers not only to the things we build and inhabit but also to the things we make and use to think about buildings, to depict and represent them, and to construct written and spoken discourse about them. Therefore, when I use the word architecture I mean not only buildings but more inclusively things-about-buildings. Photographs, drawings, written texts and narratives, poems, publications, models, exhibitions, installations, found objects—all of these, and other kinds of artifacts too numerous to list and too esoteric to effectively categorize, can be about buildings in the sense that they concretize, or make possible in specific form, different means of remembering, anticipating, and imagining our experience of buildings. Photographs of a building we have visited make it possible for us to remember the building—not only what is directly visible in the photograph, of course, but also associations, conversations, moods, and experiences that are beyond the scope of any photograph to record. Similarly, a physical model of a building can facilitate our imagination, as again we bring memories and associations to bear upon what we are seeing. Of course, written texts—including everything from descriptions in tourist guides to scholarly treatises to poems and fictional narratives—have an illimitable capacity to provoke imagination, memory, and anticipation of buildings and environments.

To repeat, I acknowledge all of these things-about-buildings as part of architecture. To distinguish things-about-buildings from buildings themselves, I also call them architectural artifacts or more usually architectural media. I’ve mentioned some obvious architectural media already—drawings, models, narratives, and photographs. These, and others I’m not naming yet, are not by-products of architectural work: they are the substance, the body, indeed the first product of architectural work. Even more importantly, architectural media are not only the substance and content of architectural work, but they actually enable architects to do what they do: to think, to act, and to construct discourse in specific ways. In my view, buildings can and do exist without media, but without media there is no architecture. (“Architects,” Robin Evans famously wrote, “do not make buildings, they make drawings of buildings.”)7

It follows that as we begin to “do” architecture, we need to select an architectural medium through which to work. That medium could be the written word, it could be sculpture, it could be sketches on paper, it could be a digital model on a computer screen, it could be paint on canvas, or performance or narrative; it could be technical pens on mylar—it could be almost anything, as none of these architectural media is inherently more essential or fundamental than any other. Architectural media are, in some way, extensions of our bodies, and as such, they structure our thinking, our actions, and our interactions with each other in specific ways.8 Whenever architects “do” architecture—that is, whenever they are learning about a building or making a proposal for a building—they make choices or selections of media with which to work. For example, architects might choose to make things like photographs or sketches in order to record what is seen; architects also make sketches as well as other drawings or models to record or test knowledge as they are generating proposals for new buildings; and architects also make things in order to see what cannot otherwise be seen—indeed, David Leatherbarrow has argued persuasively that it is precisely this quality that makes certain kinds of drawings specifically architectural.9

This act of making things-about-buildings is characteristic of architectural behavior—the act defines the profession and the discipline. It is equally characteristic of behavior whether people are learning about existing buildings by visiting them directly, or by reading about them in a book or online, or by imagining the possibilities for new buildings, installations, or cities. Take the case of direct experience—that is, of visiting an already existing building—as an example. When visiting an existing building (such as the Taj Mahal), how do architects characteristically behave? What do they make? Certainly, the act of making sketches is characteristic of architectural behavior, but the same act is also characteristic of the behavior of visual artists. The act of taking photographs is characteristic of architects visiting an existing building, but the fact that someone takes a photograph of a building does not make that person an architect. Architects often take notes or write in their journal or even compose poetry while visiting a building, but again, the act of writing does not in and of itself make someone an architect. To extend the discussion past the experience of visiting a building, consider that while proposing a new design, architects build models—but then so do automotive designers and civil engineers. Engineers are also like architects in that they commit their developing designs to paper (at least traditionally so). Theatrical designers, fashion designers, interior designers, and industrial and product designers, like architects, all engage in similar kinds of behavior while designing: they draw; they build models, prototypes, or mock-ups; they consult with clients or sponsors, as well as with other designers. Indeed, none of the characteristic behaviors I’ve mentioned is necessary for someone to be an architect, but their cumulative presence in a single person is persuasive: someone whose daily activity consists of making models of buildings, doing drawings of buildings, taking photographs of buildings, writing notes about buildings, and producing sketches of buildings is likely to be an architect. In this view, an architect can be defined as neither more nor less than a person whose daily activities consist of producing things using architectural media.10

What are those daily activities? An architect at work might produce sketches, drawings, and models, as well as photographs, whether of an existing site, or of physical models, or simulated photographs speculating about the photographic appearance of an imagined building. Architects prepare construction documents to clearly communicate forms, shapes, materials, sizes, proportions, and dimensions to contractors—although such documents represent only part of the collection of documents and information produced by architects in the course of designing a building and administering its construction. Construction documents, in turn, are similar in appearance if not in intent to “as-built” documents aiming to record a building’s existing measureable characteristics. Less obvious to someone who has not worked as an architect, or who has not studied to become one, is the (almost) daily need for architects to produce things, or artifacts, in order to develop ideas—artifacts perhaps meant for an audience of one or two people. These artifacts could be drawings, sketches, or any of the other examples cited. Architects make artifacts, in a sense, to test or provoke ideas in a substantiated form; the act of making artifacts is in turn capable of triggering new ideas and associations. This cycle of making, seeing, and making—a cycle establishing a reciprocity between things envisioned in the mind and things made—is essential to the discipline and practice of architecture, and indeed an architect’s ability to develop ideas demands this reciprocity.

It’s essential to remember that all architectural artifacts of the kinds mentioned here contain incompletenesses, abstractions, selections, and prioritizations. Architectural artifacts are, in other words, fragmentary and selective because they always reflect human choices and prioritizations. To paraphrase Michael Graves from a well-known 1977 essay,...