- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ireland in Prehistory

About this book

The authors examine Irish prehistory from the economic, sociological and artistic viewpoints enabling the reader to comprehend the vast amount of archaeological work accomplished in Ireland over the last twenty years.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ireland in Prehistory by George Eogan,Mr George Eogan,Michael Herity in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Background, Geographical and Historical

Ireland is an island in the Atlantic. She lies immediately to the west of Britain. Her sea-indented west coast is continuous with that of Atlantic Europe and with the west of Scotland and Norway, this whole long seaboard united from Cadiz to Bergen by the Atlantic Ocean. The eastern half of the country has been left far richer by Nature than the west, and it looks across a less hazardous sea towards Britain, and beyond to the Low Countries and Jutland and the mouths of the rivers Rhine and Elbe.

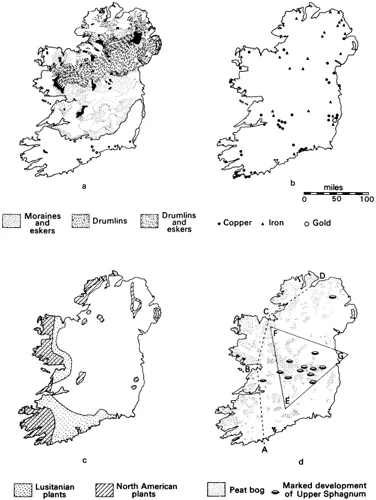

Two hundred and fifty million years ago, when the Silurian and Devonian epochs had passed, the mass on which Ireland’s foundations lie had been roughly sculpted. Her mineral wealth had already been created: the copper deposits of Avoca in Wicklow’s Caledonian foldings, the gold which presumably lies at the margin of the Leinster granite close by and, in the Armorican foldings of the south, the Silvermines deposits of Tipperary and the copper of west Cork and Kerry (Fig. 2b).

A relatively short hundred million years ago, the chalk of Antrim and Derry with its layers of flint nodules had been formed at the bottom of a Cretaceous sea (Plate 1a). Later, the ice came. An ice sheet, 300 m thick, ground and smoothed the mountains, leaving a broad central plain, opening to the sea on the east but otherwise surrounded by a ring of mountains. Most of the country was covered over with a generous depth of rich glacial mud and clay (Fig. 2a; Plate lb).

Only in winter, and then only occasionally, does Ireland today feel the intense cold of the North European Plain; even then, her western seaboard tends to remain under the influence of the mild and moist south-westerlies that blow in over the warm Gulf Stream. These winds and ocean currents have brought to Ireland a dramatic link with the flora of Spain and Portugal and even of America, for several Lusitanian and American plants exceptional in these latitudes are found in the south-west and west of Ireland (Fig. 2c). Nature has thus been generous with Ireland, endowing her with gifts of minerals, land and climate; she is ‘rich in pastures and meadows, honey and milk’ as Gerald the Welshman described her in 1185, having within her shores the best cattle-land in Europe.

Figure 2 Maps of Ireland showing (a) extent and effects of the most recent glaciation (after Charlesworth); (b) Ireland’s mineral resources; (c) the extent of plants of Lusitanian and North American origin (after Charlesworth); (d) Irish peat deposits.

Climate History

The science of pollen analysis has enabled workers in Ireland to chronicle the history of climatic change from the end of the Ice Age onwards in a series of successive eras, called zones. Raised bog deposits which began to form in the hollows of the central plain as soon as they were free of ice have grown steadily from then on to the present day, trapping and preserving on each new surface the pollens of trees and other plants which grew to windward (Fig. 2d). The analysis of these pollens under the microscope enables us to reconstruct the varying representation of significant plants as time went on and broadly to deduce a history of vegetation and climate. The detailed examination of layers of mud formed at the end of the Ice Age in Scandinavia (Varves) and the new technique of radiocarbon dating allow us to locate each pollen-zone precisely in time (Clark 1960, 143–9, 156–9; Jessen 1949; Mitchell 1951).

The story thus documented opens after the retreat of the ice-sheet with an open tundra vegetation, including dwarf willow (salix herbacea), covering Ireland. A new warmer zone began at 10,000 B.C. and lasted to 8800 B.C.; grasses and herbs appeared and birch and juniper were common. A third stage, ending at 8300 B.C., showed a regression to the earlier, open tundra vegetation, suggesting the return of a very cold climate for a brief period at the very end of the last Ice Age. Some oceanic influences can be discerned at this stage. It marks the end of the Palaeolithic or Old Stone Age in these latitudes.

With the beginning of neothermal times, in Zone IV, birch re-appeared and aspen and heather grew for the first time. This Pre-Boreal phase (8300–7500 B.C.) was still significantly colder than modern times. An expansion of hazel indicates a climatic improvement at the beginning of the Boreal phase, named from Boreas, the north wind of the Greeks (7500–6900 B.C.). In this zone, birch began to decline and oak and elm reached Ireland and grew in small numbers. By this stage, the climate was as warm as it is today. The climatic improvement continued in the next phase, still Boreal (Zone VI: 6900–5200 B.C.). Summer temperatures then reached a point at which they were higher than today, and the wind system tended towards the oceanic, favouring the growth of holly and ivy. The first signs of man are claimed for this phase, which belongs to the Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age.

An Atlantic phase, Zone VIIa (5200–3000 B.C.), in which alder flourished, brought a climax in the warm oceanic climate. In this phase the sea rose to a maximum postglacial inundation of the coasts of the north-east of Ireland, leaving behind on its retreat the Larnian raised beaches. Periwinkle (litorina littorea), a lover of warm waters, was now as common on these shores as it was in the contemporary Litorina raised beach of the Baltic.

Whereas in the period that has gone before, Nature has determined the changes in vegetation, it is probably the influence of man in initiating forest clearance that gives rise to the next or Sub-Boreal phase (Zone VIIb). The arrival of the farmers of the Neolithic or New Stone Age period may have thus caused the elm decline sometimes taken as the distinguishing mark between Zone VIIb and the preceding VIIa. This phase (3000–1000 B.C.) was drier and warmer, as much as 2.5° C. better than today, with less oceanic wind-cycles. Oak was very common, and birch and pine grew 1000 ft above their present limits on the mountain sides. A return to the wetter, temperate climate of today came with the Sub-Atlantic, about 1000 B.C. (Zones VIII-X). It was about this time, or a little before, that the blanket bogs of the higher mountains and of the west of Ireland started to grow, enveloping the tombs and farmsteads of the first farmers and their successors and thus preserving them. The population by now had grown to proportions big enough to have an even more significant influence on the vegetation through tree clearance and the growing of crops.

It was against this backdrop of changing climate and plant life that ancient man in Ireland acted out his story, looking to the land, the riches within it, and the plants, crops and animals feeding off it, for his material necessities. We turn now to another story, the history of how our present knowledge of the ancient drama has developed over the last centuries.

The story of antiquarian thought can help us to appreciate the kind of questions asked in modern archaeology. It can also indicate sources in which useful information about the context of older finds may be obtained, and give us significant insights into the cultural history of Ireland. Although things ancient were much prized in the Celtic tradition, a study of modern Irish antiquarianism can conveniently begin about the year 1600.

History of Irish Archaeology

The English antiquarian tradition, newly begun by William Camden and the Elizabethans, was taken up in Dublin at the beginning of the seventeenth century by Ussher and Ware. Both these men made contact with the scholars of the native Irish tradition who could interpret for them the old Irish chronicles and the mythical Celtic history of Ireland’s origins. The native tradition was dying with the break-up of Irish society after the Flight of the Earls in 1607, and the Franciscans, like Colgan on the continent and the Four Masters at home, whose Annals were compiled at Bundrowes in Donegal between 1632 and 1636, were doing what they could to commit authoritative versions of it to paper before it was lost forever. Sir James Ware (Plate 2a), whose Antiquities was first published in 1654 and in a revised version in 1658, employed as his interpreter An Dubhaltach Mac Fir Bisigh, one of the Mac Fir Bisigh family of Lacken, near Ballina in Co. Mayo, the hereditary learned family of the O’Dowdas (Herity 1970a), one of whose forbears, Giolla Íosa Mór, had written the Great Book of Lecan in 1418.

When the Dublin Philosophical Society was founded by William Molyneux and Sir William Petty in 1683, this collaboration between the new and the native antiquarian traditions was continued: Thady Rody of Fenagh in Co. Leitrim was asked to write descriptions of his native county and of Longford, and Roderick O’Flaherty, who was at that time finishing his Ogygia (1685), wrote a description of Iar-Connacht. Though the new spirit recognized the value of legendary history, this attitude did not bring any significant results in Ireland until the coming of Edward Lhuyd in 1699. Lhuyd, who was Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, and who had conceived a plan of investigating the language, antiquities and natural history of Wales, Scotland and Ireland, was to spend almost a year in Scotland and Ireland. In August of that year, Lhuyd arrived in Dublin with three young helpers, David Parry, Robert Wynne and William Jones. There they split forces: Jones and Wynne were sent west and south with specific instructions to reconnoitre and record the geology, botany, history, antiquities and folklore of the country, while Lhuyd himself and Parry went northwards to Antrim and into Scotland to return to the north and west of Ireland in January of 1700 (Campbell 1960). Though Lhuyd’s original notebooks have almost entirely perished, several letters of his are extant as well as copies of the drawings made by the party, which were rescued by John Anstis immediately after Lhuyd’s death in 1709 (British Museum MSS. Stowe 1023, 1024). Among the antiquarian drawings and descriptions are several of New Grange, of the High Crosses at Monasterboice, of the monuments around Cong in Co. Mayo, of megalithic tombs around Donegal Bay, and of the monastic remains at Clonmacnois on the Shannon. Lhuyd’s observations were perceptive and rational (Herity 1974, 1–2). In all, about sixty monuments are drawn in the Anstis notebooks, a cross-section of Ireland’s monuments not equalled until the Ordnance Survey began its work in the late 1820s. Volume 1 of the Archaeologia Britannica, embodying some fruits of his linguistic researches, was published in 1707, and he died in 1709. Had Lhuyd lived to complete Volume 2 of this work, an incisive analysis of the monuments, their folklore and their legendary history would have been produced. As it was, this was not to be done until O’Donovan and Petrie began their work with the Ordnance Survey well over a century later.

The eighteenth century began with the issuing of a number of editions of Ware’s Antiquities translated into English. Sir Thomas Molyneux, a medical doctor, who became the state physician in Ireland, and brother of William Molyneux, also republished Gerard Boate’s geographical work, the Natural History of Ireland, published originally in 1653 for the benefit of Cromwellian planters; with this he included several articles written under the aegis of the Dublin Philosophical Society and published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, as well as his own essay asserting the Danish origin of the Round Towers and of New Grange, the Discourse concerning the Danish Mounts, Forts and Towers in Ireland (1726).

Walter Harris, who brought out the most extensive and useful edition of Ware’s Antiquities (1764), was one of the members of another Dublin group, the Physico-Historical Society, a society consisting mainly of noblemen, who met for the first time in the Lords’ Committee Room of the Parliament House in Dublin in April 1744. Its members described themselves as ‘a voluntary society for promoting an enquiry into the Ancient and Present State of the several Countys of Ireland’. Harris, a Dublin lawyer, and Charles Smith, an apothecary from Dungarvan in Co. Waterford, published a description of Co. Down in 1744. Smith went on to publish descriptions of Cos Waterford (1746), Cork (1750), and Kerry (1756), and to assemble the materials for a description of the rest of Munster. James Simon’s Coins was also published under its aegis (1749) but, had he not communicated them to the Society of Antiquaries at London, drawings and descriptions of several Irish prehistoric antiquities found about that time would have been lost. Several valuable accounts written by Dr Pococke, Bishop of Ossory, would also have been lost had they not been communicated to the same Society (Pococke 1773; Herity 1969).

About 1770, the new romantic spirit brought a surge of interest in the past. In that year, Major (later General) Charles Vallancey began the publication of his Collectanea de Rebus Hibernicis of which six volumes in all were to appear by 1804 (Plate 2b). The first publication was Sir Henry Piers’s Chorographical Description of the County of West Meath written for the Molyneuxs in 1682. The title page of volume 1 describes Vallancey as Soc. Antiq. Hib. Soc., but apart from other equally oblique references, little is known of this Hibernian Antiquarian Society. The original purpose of the Collectanea (1770–1804) was to publish the writings of earlier workers like Ware, Camden and Lhuyd, but soon the only contributions were those of Vallancey himself, ‘inspired omniscient antiquary’, whose quotations in Arabic, which he had learnt during a sojourn in Gibraltar before coming to Ireland, were to exhaust the stocks of Arabic type in all the Dublin printing presses:

THE Author, desirous of printing the Arabic words in their proper characters, prevailed on the printer to borrow all the Arabic Types, this city afforded; after all endeavours to compleat the alphabet, but one Kaf and no final Nun, could be found, and several deficiencies in the points appeared. We were therefore under the necessity of writing most of the Arabic words in Roman letters, adopting the sound in the best manner we could.

(Collectanea, vol. 5, iv)

In May 1772, the Royal Dublin Society, which had been established in 1731 for the improvement of farming and industry, founded a Committee of Antiquities. Joint secretary with Vallancey was Edward Ledwich, Dean of Aghaboe and author of the Antiquities of Ireland (1790). Not to be outdone by Vallancey, he deciphered writing ‘in Bebeloth characters’ on the face of one of the High Crosses at Castledermot. As the Molyneuxs and the Physico-Historical Society had earlier done, this committee sent out a questionnaire seeking antiquarian information; its most important act, however, was to advertise in the continental gazettes seeking manuscripts which would have been taken abroad by Irish noblemen, soldiers and clerical students after the Williamite Wars and during the Penal times.

Some of the most valuable work done in this period was done under the influence or patronage of William Burton Conyngham of Slane in Co. Meath, who was a Lord of the Treasury at Dublin Castle and who, after coming into his inheritance in 1779, devoted much of his private money to antiquarian research (Plate 2c). He engaged two artists, Gabriel Beranger (Plate 2b) and Angelo Bigari, a scene-painter at the Smock Alley Theatre, and sent them on two tours, one to Sligo and the west, the other to Wexford, to plan and describe antiquities (Wilde 1870). Bigari’s drawings were afterwards published in full by Grose (1791), but not Beranger’s, though a number of his were used by Vallancey and, afterwards, by Petrie. This group of ‘Castle’ antiquaries included Austin Cooper, who was a clerk in the Treasury at Dublin Castle and who also acted as a landlord’s agent. A number of his published drawings indicate the interests of a typical antiquary of this school and period: old castles, churches and towers, earthworks like Norman mottes and ring-forts and megalithic tombs (Price 1942). Because of the difficulties of travelling, many of the drawings in his collection are copies from those of other artists and antiquaries; several of Cooper’s, for instance, are the work of Vallancey, Lord Carlow, Jonathan Fisher and of Cooper’s cousins Turner and Walker.

The Royal Irish Academy, founded in 1782, had a good deal in common with the contemporary movements. The scholars connected with it were mainly from Trinity College and they included Antiquities with Polite Literature in the scope of their inquiries; their Transactions, the first volume of which commenced in 1785, contained an account of a Bronze Age Urn from Kilranelagh in Co. Wicklow. Other objects donated as a result of the investigations of Vallancey and Conyngham were placed in the Trinity College Museum for safe-keeping. A scholar who was sought after by all the different bodies of Dublin antiquaries was Charles O’Conor of Belanagare in Co. Roscommon, an Irishman trained in the native learning, the equivalent in the eighteenth century of Mac Fir Bisigh, Rody and O’Flaherty in the seventeenth, whom the Dublin antiquaries of that day had also sought out.

The Ordnance Survey

With the passing of the Act of Union in 1800, the Ascendancy dilettanti left Dublin for London and antiquarian work went into decline for want of private patrons. When the Ordnance Survey was set up in 1823, it was now the turn of the State to provide the patronage. Travel was becoming easier in this century, with the building of roads and canals and, later, railways. Printing technology was improving and wider markets for printed works were being created with the growth of popular education: the Irish National Schools system was set up in 1829.

The Irish Ordnance Survey was founded to provide a set of detailed and authoritative maps on which a new valuation of land could be based. The trigonometrical survey was begun in 1824 under the direction of Colonel Thomas Colby, who commanded the Survey Corps, a branch of the army with headquarters at Mountjoy House in the Phoenix Park in Dublin. In 1828, Lieutenant Thomas Larcom was appointed to assist Colby in the work of surveying and engraving the large-scale maps, the wo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Background, Geographical and Historical

- 2 Stone Age Beginnings: Hunter-Fishers and First Farmers

- 3 The Boyne Culture: Passage Grave Builders in Ireland and Britain

- 4 Late Neolithic: Single Burials, New Technology and First Central European Contacts

- 5 Beaker Peoples and the Beginnings of a New Society

- 6 Food Vessel People: Consolation of the Single Grave Culture

- 7 Urn People: Further Arrivals and New Developments

- 8 Industrial Changes Late Second-Early First Millennia

- 9 Final Bronze Age Society

- 10 Later Prehistoric Events: The Iron Age and the Celts

- 11 Retrospect

- Bibliographical Index

- Index