![]()

Chapter 1

Conservation and Context: Different Times, Different Views

Introduction

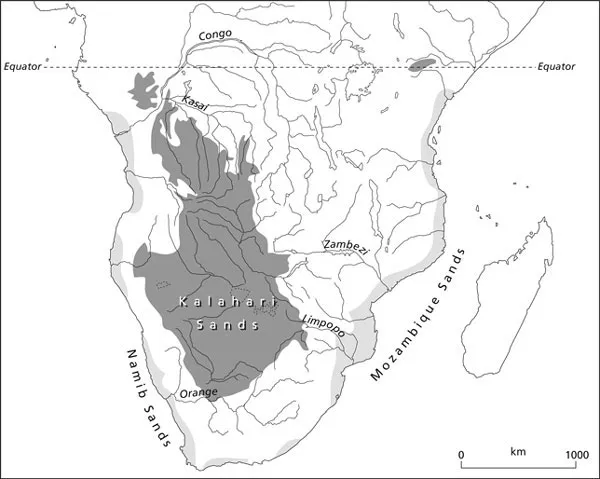

Throughout the world, wild, naturalized or non-cultivated plants provide a ‘green social security’ to hundreds of millions of people, for example in the form of low-cost building materials, fuel, food supplements, herbal medicines, basketry containers for storage, processing or preparation of food crops, or as a source of income. Edible wild foods often help prevent starvation during drought, while economically important species provide a buffer against unemployment during cyclical economic depressions. This is particularly important for people living in areas with drought-susceptible soils of marginal agricultural potential, such as the vast areas of sub-equatorial Africa covered by leached, nutrient-poor sands (Figure 1.1). Despite the immense importance of these plant resources, their value is rarely taken into account in land-use planning; and when it is, it is often assumed that these species are sustainably harvested and that this ‘green social security’ will always be available to provide a safety net for resource users. This is not always true. Although many ecosystems and harvested species populations are resilient and have a long history of human use, they can be pushed beyond recovery through habitat destruction or overexploitation.

Source: Cooke, 1964

Figure 1.1 Soils are a major determinant of reliance on plant use. In Africa, for example, the distribution of leached, nutrient-poor and drought-susceptible sands of the coast (light grey shading) and Kalahari basin (dark grey shading) affects most land users. Whether they are hunter-gatherers, pastoralists or farmers, people remain dependent to some extent upon wild plants (and the associated edible insects) for food supplements, housing, fuel, furniture and fibre for household containers

Cultural systems are even more dynamic than biological ones, and the shift from a subsistence economy to a cash economy is a dominant factor amongst all but the remotest of peoples. In many parts of the world, ‘traditional’ conservation practices have been weakened by cultural change, increased human needs and numbers, and by a shift to cash economies. There is a growing number of cases where resources which were traditionally conserved, or which appeared to be conserved, are today being overexploited. The people whose ancestors hunted, harvested and venerated the forests that are the focus of enthusiastic conservation efforts are sometimes the people who are felling the last forest patches for maize fields or coffee plantations, often on slopes so steep that sustainable agriculture is impossible. In other areas, local human populations have decreased due to epidemic disease or even urbanization, with swidden agriculture only occurring on old secondary forest. While some resources are being overharvested due to cultural and economic change, the majority are still used sustainably, and the impact on others has lessened because of social change. In the most extreme cases, ‘islands’ of remaining vegetation, usually created by habitat loss through agricultural clearance, then become focal points for harvesting pressure, and are sites of conflict over remaining land or resources.

For all interest groups, whether resource users, rural development workers or national park managers, it is far better to have proactive management and to stop or phase out destructive harvesting in favour of suitable alternatives before overexploitation occurs, than to have the ‘benefit’ of hindsight in the midst of a devastated resource. Marilyn Hoskins (1990) puts this well in her paper on forestry and food security:

All research and management by outsiders must remember that their activities come and go, but food security – land and resources surety – is a long-term, life and death issue for rural peoples.

Historical Context

Since the 1960s, the approach to conservation in developing countries has broadened from its past emphasis on strictly policed protected areas, or land set aside for large mammals or spectacular landscapes. Nowadays the emphasis has shifted to sustainable resource use and the maintenance of ecological processes and genetic diversity and a broader approach involving land users in ‘bioregional’ management at an ecosystem level.

This broader approach is evident in the different IUCN categories of protected areas which were developed in the mid 1980s and recently modified at the IV World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas (Box 1.1). It also represents a change from one where intervention by the state (by government) through proclamation of national parks was seen as the solution, to one where the conservation roles of private landowners and residents of communal lands are recognized. It also became widely accepted that the future of most conservation areas largely depends upon the acceptance and support of the surrounding human populations. In Africa, for example, the consequences of political turmoil, changes of government and a ‘brain drain’ of park biologists and policy makers, reinforce Jonathan Kingdon’s (1990) point that:

Box 1.1 IUCN Protected Area Categories: The Modified System of Protected Areas Categories Agreed at the IV World Congress on National Parks and Protected Areas, 1992

1 Strict Nature Reserve/Wilderness Area

Areas of land and/or sea possessing some outstanding or representative ecosystems, geological or physiological features and/or species, available primarily for scientific research and/or environmental monitoring; or large areas of unmodified or slightly modified land, and/or sea, retaining their natural character and influence, without permanent or significant habitation, which are protected and managed so as to preserve their natural condition.

2 National Park

Protected areas managed mainly for ecosystem conservation and recreation. Natural areas of land and/or sea, designated to:

- Protect the ecological integrity of one or more ecosystems for this and future generations.

- Exclude exploitation or occupation inimical to the purposes of designation of the area.

- Provide a foundation for spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational and visitor opportunities, all of which must be environmentally and culturally compatible.

3 Natural Monument

Protected areas managed mainly for conservation of specific features. Areas containing one or more specific natural or natural/cultural features of outstanding or unique value because of their inherent rarity, representative or aesthetic qualities or cultural significance.

4 Habitat/Species Management Area

Protected areas managed mainly for conservation through management intervention. Areas of land and/or sea subject to active intervention for management purposes in order to ensure the maintenance of habitats and/or to meet the requirements of specific species.

5 Protected Landscape/Seascape

Protected areas managed mainly for landscape/seascape conservation and recreation. Areas of land, with coast and sea as appropriate, where the interaction of people and nature over time has produced areas of distinct character with significant aesthetic, cultural and/or ecological value, and often with high biological diversity. Safeguarding the integrity of this traditional interaction is vital to the protection, maintenance and evolution of such areas.

6 Managed Resource Protected Area

Protected areas managed mainly for the sustainable use of natural ecosystems. Areas containing predominantly unmodified natural systems, managed to ensure long-term protection and maintenance of biological diversity, while providing at the same time a sustainable flow of natural products and services to meet community needs.

Source: IUCN

‘… the realities of power are exactly the opposite to those perceived by most of the participants of this struggle to conserve key areas of high endemism and biodiversity because the long-term future of Africa’s Centres of Endemism lies with local peasantries rather more than with transient governments or enthusiastic conservationists; yet locals seldom receive the respect that is generally accorded to those that wield power. Meanwhile, both populations and resentments grow.

… The conservationists’ answers should not lie in propaganda campaigns, which are generally seen for what they are, but in a shared growth of knowledge and debate. The minimal demands of local communities will include sustained, not ephemeral, programmes of action in which their own people can find meaningful, decisive and dignified roles.’

At a meeting in Tanzania in the 1960s, Sir Julian Huxley suggested that the means to justify conservation as a form of land use to local people or national governments centred upon ‘pride, profit, protein and prestige’. Little attention was paid to wild plants and their importance to rural people. This is no longer the case. There is now a strong emphasis on sustainable use of resources, including wild plants, and the involvement of national governments and local people in conservation. Buffer zones, formed around strictly protected core conservation areas, have been one of the tools in this process and are a characteristic planning tool of biosphere reserves established by the UNESCO Man and Biosphere programme. This approach is embodied in many recent policy documents, such as the World Conservation Union’s (1991) strategy document Caring for the Earth, and more recently, the World Resources Institute’s (1992) Global Biodiversity Strategy (WRI, 1992) and the World Convention on Biological Diversity (see Glowka et al, 1994).

Policies on sustainable development or calls for sustainable use of resources by local people within protected areas (for example, Ghimire and Pimbert, 1997) are fine on paper. The challenges arise with their implementation. In their review of conservation projects, trying to make a link between parks and people through planning of buffer zones and links to development (which they termed Integrated Conservation and Development Projects), Michael Wells and Katrina Brandon (1992) found very few buffer zone models which they were convinced worked well. As usual, ‘the devil is in the details’: and if policies are impractical, they are worthless. If implementation results in resource degradation rather than the sustainable use intended, then the self-sufficiency of resource users is further reduced, increasing the likelihood of land-use conflict between national parks and people. This manual is about one of those details: the sustainable harvesting of wild plant resources.

Management Myths and Effective Partnerships

Policy changes towards sustainable use of resources in conservation areas have placed many field researchers and national parks managers in a dilemma. How do we go beyond the rhetoric of policy on human needs and sustainable resource use without jeopardizing the natural resource base or primary goal of the conservation area: the maintenance of habitat and species diversity? This is no easy task. The higher the number of harvesters, the more uses a plant species has. The scarcer the resource, the greater the chance that resource managers and local people will get embroiled in a complex juggling of uses and demands, in an attempt at a compromise that could end up satisfying nobody.

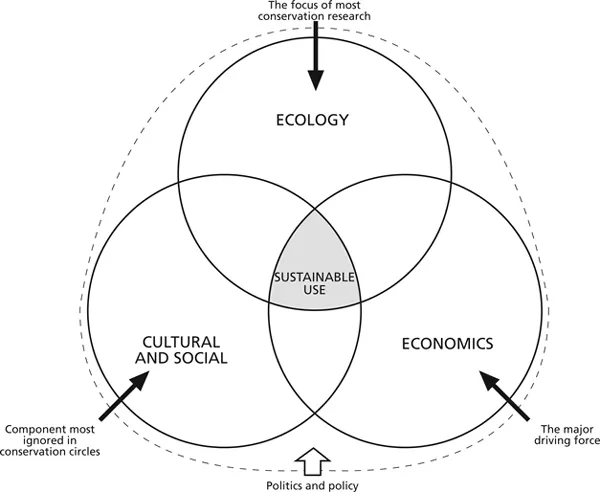

In theory, sustainable harvesting of plants from wild populations is possible, but is often more complex than the urban biopoliticians and policy makers think. Sustainable management of wild plant use by people depends as much upon an understanding of the biological component as it does on the social and economic aspects of wild plant use. Without an understanding of ecological, political and socio-economic factors (Figure 1.2), plans for sustainable use are likely to fail.

Source: Martin, 1994

Figure 1.2 Achieving sustainable use of resources requires cross-disciplinary work at the confluence of the social sciences, economics and ecological studies, all within a political (and policy) framework

Sustainable use of resources by local people and the concept of ‘extractive reserves’ appear to have been promoted in developing countries on the basis of two commonly held assumptions that:

- Local (or indigenous) peoples have been harvesting these resources for thousands of years, with no detrimental effects on harvested populations. Traditionally, many useful biological resources have been valued and conserved. Therefore if ‘resource sharing’ between national parks and neighbouring peoples takes place in buffer zone areas, then the people living around that national park will have an interest in conserving resources for the future, and will harvest these resources in a sustainable way.

- Wider recognition for wild plant products, whether from forests, savanna or wetlands, will result in more appropriate values being placed on vegetation currently being damaged for a few products (hardwood timberlogging, charcoal) or cleared for agriculture or pasture, ignoring other protective (eg watersheds) and productive (nuts, oils, fibres, etc) functions.

While there is some truth in these assumptions, they have reached almost mythical proportions, with the result that local resource users are often considered natural conservationists who have always used natural resources sustainably. There is no doubt that ‘traditional’ conservation practices existed in many societies, and that these have buffered the effects of people on favoured species and in selected habitats. Customary restrictions can also be an important guide to culturally acceptable limits on the harvesting of vulnerable species (see Chapter 6). Equally, there are many examples of resource overexploitation prior to the introduction of firearms and more efficient hunting technologies or large-scale, species-specific commercial trade.

Also often glossed over is the fact that protected areas, particularly those with a high species diversity and vulnerability to overexploitation, require a level of detailed management that is not possible with the economic constraints that are a feature of many conservation departments. Despite increased awareness of environmental concerns and international backing for conservation, many national parks have inadequate staff or funding to control often large protected areas. The level of responsibility faced by two young Ugandans supported through the People and Plants Initiative provides a typical example: one Ugandan is the only ecological monitoring officer for Rwenzori Mountains National Park, 1300km2 in extent. The other is warden of Semliki National Park, 219km2 in...