- 76 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Sustainability in the Public Sector provides a quick-start guide for a wide variety of public sector stakeholders, equipping them with knowledge of both the sustainable development challenges and the political backdrop to this agenda.This guide: uncovers the history of the term "sustainable development" and introduces basic sustainability theory; highlights the realities of the politics behind the sustainable development agenda, alongside the responses of successive political administrations; provides a snapshot of how sustainable development in local government is developed and demystifies the roadmap for achieving the UK's 2050 carbon reduction targets.This book will be invaluable to a variety of public bodies, such as local authorities, and their stakeholders, including councillors, officers, members of Local Enterprise Partnerships, Local Nature Partnerships, scrutiny panels and other forums, in enhancing understanding of both the sustainable development challenge facing us today and the political backdrop to this agenda.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sustainability in the Public Sector by Sonja Powell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Wirtschaftssethik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Understanding the Issues

Sustainable development means meeting the needs of the present, without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs.

(Brundtland Report, 1989)

THIS CHAPTER PROVIDES ESSENTIAL background knowledge, introducing the reader to the field of sustainable development. The first step is to build common understanding of what is meant by the term ‘sustainable development’ through uncovering the history of the term and introducing basic sustainability theory. This leads the way to considering the scope of the challenge faced, which is achieved by highlighting current unsustainable practices.

What is sustainable development?

Many people are unsure what is meant by the phase ‘sustainable development’. One reason for this is the scope of the topic; it is wide-ranging and it is often necessary to check what aspect of sustainability is being referred to. The terms ‘sustainability’ and ‘sustainable development’, which are used interchangeably in this book, mean meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs. To support a fuller understanding, the background to the term ‘sustainability’ is provided below, followed by an introduction to sustainability theory and how it differs from economic theory.

Dyllick and Hockerts (2002) offer a history to the term ‘sustainability’ and its dimensions. It has emerged from distinct stakeholder groups as follows:

1972: Ecologists constructed sustainability as a concept concerned with the protection of the environment. The United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (in Stockholm), called on states and international organizations to “play a co-ordinated, efficient and dynamic role for the protection and improvement of the environment”.

1970s onwards: Business strategy scholars searched for sustainable competitive advantage.

1987: The Brundtland Commission emphasised the link between the economic plight of developing countries and sustainable development. They defined sustainable development as: ‘meeting the needs of the present, without compromising the ability of future generations to meet theirs’.

1990s: United Nations conferences in the 1990s added the notion of social sustainability in debates on education for all, human rights, population and development, women, and social development.

Sustainability theory

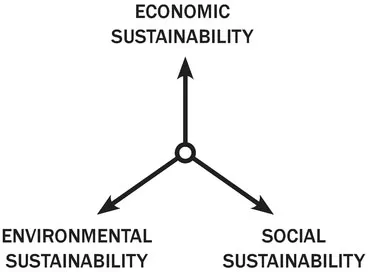

Three emerging dimensions arise from the above history. These are illustrated in the ‘triple bottom line’ which is made up of the environmental case, the social case, and the business case for sustainability. Figure 1 is an illustration of the three dimensions of sustainability. Elkington’s model below is both easy to understand and widely used.

FIGURE 1. The three dimensions of sustainability, known as the triple bottom line. SOURCE: Dyllick and Hockerts (2002) and Elkington (1997).

‘Triple bottom line’ is now standard sustainability theory and illustrates that the financial or ‘single bottom line’ traditionally used by organisations is insufficient for overall sustainability. The overemphasis on short-term economic gain has largely ignored longer-term costs caused by social and environmental damage.

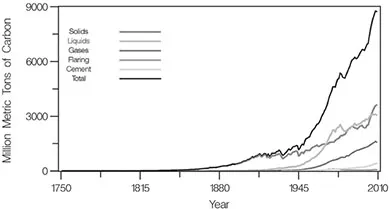

In economic theory, ‘burned soil’ (where natural and social resources have been depleted without much concern for potential future costs) represents externalities or market failure. Long-term economic sustainability is threatened by the burned soil effect. An example of this effect is provided in Figure 2, which shows global carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning between 1751 and 2010. It illustrates that since the Industrial Revolution there has been a dramatic increase in carbon emissions.

FIGURE 2. Global carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning. SOURCE: Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center (CDIAC).

The solution is for organisations, already used to maintaining their economic capital base, to also manage their natural and social capital in order to achieve long-term sustainability. In economic models the role of government is to correct market failure, suggesting that government should be acting to correct and prevent unsustainable development by supporting organisations in their management of all three types of capital which make up the triple bottom line.

Clarity on the three types of capital is provided by Dyllick and Hockerts (2002) as follows:

- Economic capital: economic sustainability requires the management of several types of capital – financial capital (i.e. equity and debt); tangible capital (i.e. machinery, land and stocks) and intangible capital (i.e. reputation, inventions, know-how, organisational routines).

- Natural capital: this includes natural resources in renewable form (i.e. wood, fish, corn) and non-renewable form (i.e. fossil fuel, biodiversity, social quality); and ecosystem resources (i.e. climate stabilisation, water purification, soil remediation, reproduction of plants and animals).

- Social capital: this is divided into human capital (i.e. skills, motivation, and loyalty of staff and business partners); and societal capital (i.e. quality of public services like education, infrastructure, culture supportive of entrepreneurship).

In managing economic capital, different types of capital can be substituted. However, many forms of social and natural capital cannot be replaced by economic capital. We cannot for example substitute the ozone layer with other resources. Additionally, many capital types complement each other and are multi-functional, for example, forests and oceans act as sinks that absorb, neutralise or recycle wastes; forests also provide wood, paper, etc. and habitats for biodiversity. Finally, there are ethical considerations; even if no financial value has been put on a particular species, are we not morally and ethically required to protect it? Biodiversity is being lost at an alarming rate; when we lose a species this is irreversible.

Unsustainable development

We have seen that the global ecosystem is finite and fixed, and that economic activity transforms natural products into wastes that nature must then absorb. Nature’s capacity to absorb wastes is now being pushed to, and in some cases well beyond, its limits. Sara Parkin (2010) refers to five ‘symptoms’ of unsustainable development caused by current practices. These are summarised below (facts and figures used here provide a macro-picture; local statistics could be compiled for a micro-perspective):

1. Persistent poverty, injustice and inequality of opportunity for many people. The number of people classed as living in extreme poverty, defined as living on less than $1.25 per day, is 1.29 billion or approximately 22% of the world population (World Bank Development Research Group, 2012). A quarter of children are undernourished. UNHCR 2011 statistics show rising numbers of people forcibly displaced worldwide at 43.7m people, the highest number in 15 years, with the number of refugees at 15.4 million to the end of 2009.

The next symptom of unsustainable development points to competition for scarce resources as an increasingly important factor in provoking and perpetuating violence, one of the drivers behind these statistics.

The next symptom of unsustainable development points to competition for scarce resources as an increasingly important factor in provoking and perpetuating violence, one of the drivers behind these statistics.

2. Mineral depletion including platinum, phosphorus, nickel, lead, indium, gold, copper, zinc, silver, aluminium, uranium, chromium, etc.: Many minerals are already in short supply or hard to extract; extraction also adds to CO2 emissions. Minerals are used in everyday items such as digital and telecommunications and renewable energy technologies. Stocks of fossil fuels including coal and oil are also diminishing. Parkin (2010) raises the point that violent conflicts over mineral resources are on the increase (the conflicts in eastern Congo, where fighting has continued over 15 years driven by the trade in valuable minerals, are an example) and part of an overall picture of shortages of non-biological and therefore non-renewable resources worldwide.

3. Biological resource depletion including minerals, oil, water, soil fertility, forests, grass and wetlands. The 2005 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) on the state of the global environment found that 15 of 24 ecosystem services (60%) are being degraded or used unsustainably, including fresh drinking water.

Changes in ecosystems due to human activity have been more rapid and extensive in the last 50 years than in any comparable period of time. Resources have been used to meet rapidly growing demand for food, fresh water, timber, fibre and fuel. This activity has contributed to substantial gains in human well-being and economic development. However, it has also resulted in a significant and often irreversible loss of the diversity of life on Earth. If the problems are not addressed now, future generations will experience a sizeable loss in benefits from ecosystems. The World Wide Fund for Nature calculates that we are exceeding the planet’s ability to regenerate by about 30%.

Changes in ecosystems due to human activity have been more rapid and extensive in the last 50 years than in any comparable period of time. Resources have been used to meet rapidly growing demand for food, fresh water, timber, fibre and fuel. This activity has contributed to substantial gains in human well-being and economic development. However, it has also resulted in a significant and often irreversible loss of the diversity of life on Earth. If the problems are not addressed now, future generations will experience a sizeable loss in benefits from ecosystems. The World Wide Fund for Nature calculates that we are exceeding the planet’s ability to regenerate by about 30%.

4. Waste generation. The natural environment has its own efficient recycling system. However, it is overloaded by alien substances: visible rubbish such as plastic, packaging, rubble, etc. and invisible air and waterborne pollutants including man-made chemicals and fertilisers, excessive CO2, etc. Consider just one example of waste: plastic bags represent a fraction of 1% of waste generated, but cause much greater damage. Sean Poulter and David Derbyshire when launching the cam...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Abstract

- About the Author

- Who is This Book For?.

- Contents

- 1 Understanding the Issues

- 2 The Politics of Sustainable Development

- 3 Sustainability Responses of UK Political Administrations

- 4 Where Are We - A Picture of Sustainability in Local Government

- 5 What Next?

- Bibliography