![]()

1

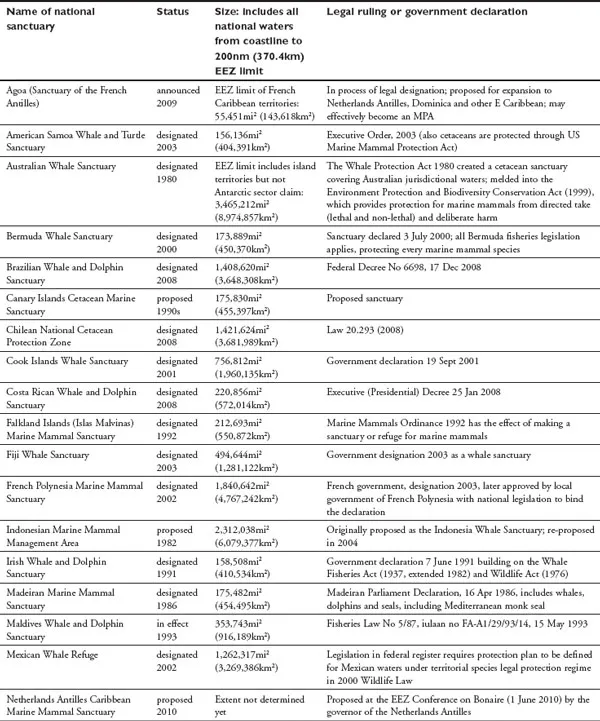

From Whale Sanctuaries to Marine

Protected Areas: Approaches to

Protecting Cetacean Habitat

History of Marine Protected Areas and Cetaceans

Glacier Bay, located in Alaska, has the distinction of being the oldest marine protected area (MPA) in the world to offer some protection to cetacean habitat. Glacier Bay National Monument was established in 1925, while Alaska was still a territory, some 34 years before it became the 49th state of the US in 1959. The national monument covered both land and adjacent water areas. The scenic beauty of the glacier and the bay were the main reasons for protection; whales were, at most, occasional visitors.

During the 1960s, it came to the notice of scientists that humpback whales were spending parts of the summer in and around Glacier Bay. The first humpback photographic identification (photo-ID) in Alaska was taken in Glacier Bay in 1964. The humpbacks arrive every June from tropical waters (Hawaii or México) to spend the northern summer feeding in and around the park. The popularity and high profile of humpbacks, with their bubble-net and group-feeding activities, fuelled substantial tourism interest, as well as new scientific research and conservation initiatives, to try to give greater protection to the area by controlling fishing and tourism within the park.

The first MPA specifically aimed at protecting cetaceans was Laguna Ojo de Liebre (Scammon’s Lagoon), established by the Mexican government in January 1972 to protect a prime gray whale mating and calving lagoon. This was the core of the area that in 1988 was expanded to include Laguna San Ignacio and part of Laguna Guerrero Negro, all of which together became El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve (see Figure I.2, p14). Among cetaceans, gray whales have some of the most obvious habitat requirements because they bring their calves every winter to semi-enclosed saltwater lagoons on the west coast of Baja California, México. Gray whales have also been among the most susceptible to decline due to human impact. During the mid 19th century, the whaler Captain Charles Scammon’s discovery of the Baja lagoons almost drove gray whales to extinction in a matter of a few decades. They were easy pickings. More recently, it has become obvious that the lagoons must be protected not just from whaling, but also from human encroachment due to excessive boat traffic, fishing gear and nets, pollution from local settlements, and industrial degradation of nearby land as well as marine areas.

As more has been learned about other cetaceans, marine habitats have been uncovered and new MPAs have been discussed and proposed. Cetacean scientists have identified:

• the humpback whale’s tropical mating and calving grounds in the Caribbean and in various locations across the Pacific;

• the deep water canyons off Nova Scotia where northern bottlenose whales live;

• the inshore feeding and breeding areas of bottlenose dolphins, tucuxi, Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins and harbor porpoises in dozens of locations; and

• the rubbing beaches, playing and resting spots, and prime feeding areas of killer whales around Vancouver Island in the North Pacific.

All of these discoveries have led to the creation of valuable MPAs. Most of this only began to happen, however, during the 1990s. Recent discoveries about blue whale habitat off British Columbia, California, México and Costa Rica have important implications for ensuring the recovery of this endangered species in the North Pacific. Recommendations include building a huge network of MPAs in addition to the existing Californian and Mexican MPAs where blue whales are sometimes found. Others see the limitations of trying to impose a spatial plan on such a wide-ranging species covering a vast area. There remains much to learn about the habitat needs of every population of every species of cetacean.

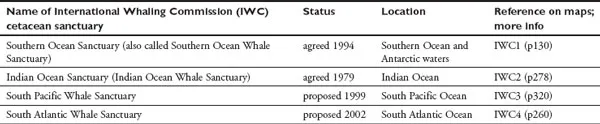

In addition to MPAs, over the years there have also been moves, mainly within the International Whaling Commission (IWC), to declare large areas of the high seas, even entire ocean basins, as ‘whale sanctuaries’ (see Table 1.1 and Figure 1.1). In 1979, an IWC majority voted to create the Indian Ocean Sanctuary, based on a resolution put forward by the IWC representative of the Seychelles. This sanctuary, which covers nearly 4 million mi2 (10 million km2), is intended to protect whales from whaling on their mating and calving grounds as well as on some, but not all, of their feeding grounds. The precise species remit of the IWC continues to be debated, but the sanctuary is generally taken to cover only the large whales and not the small whales, dolphins and porpoises that are not listed on the IWC schedule and many of which are killed in large numbers throughout the Indian Ocean as the bycatch of various fisheries (Leatherwood et al, 1984). Thus, the sanctuary designation falls short of providing comprehensive protection for cetaceans or cetacean habitat (Leatherwood and Donovan, 1991). However, the sanctuary has stimulated considerable research and some commercial whale watch operations. A 2002 review of the Indian Ocean Sanctuary by the IWC Scientific Committee featured a substantive paper detailing scientific work in the sanctuary (de Boer et al, 2002). Although, in general, research and conservation could be said to be at an early stage, the paper highlights the role of the Indian Ocean Sanctuary in furthering research, management plans, conservation strategies and other regional initiatives.

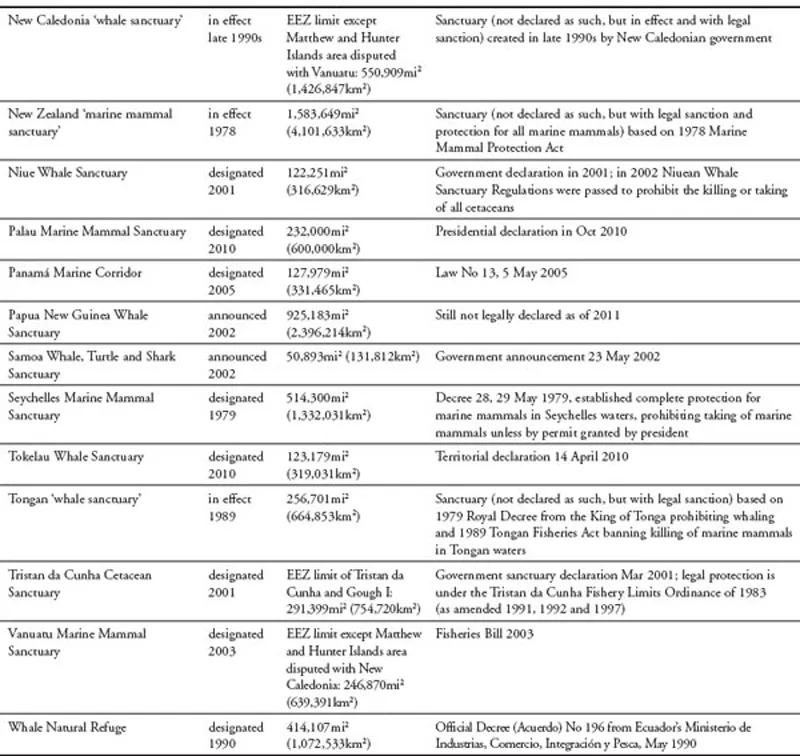

Table 1.1 Proposed and existing IWC cetacean sanctuaries

Figure 1.1 Map of International Whaling Commission (IWC) sanctuaries

Source: Boundaries as agreed by the IWC and proposals submitted to the IWC

Fifteen years after the designation of the Indian Ocean Sanctuary, in 1994, the IWC approved the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary, more commonly referred to as the Southern Ocean Sanctuary, which covers the waters of Antarctica (see p130). In 1999, the proposed South Pacific Whale Sanctuary was turned down. The South Pacific proposal and subsequent South Atlantic Sanctuary proposal have been kept alive by southern hemisphere nations. Also in 1999, Greenpeace, joined by other conservation organizations, began to circulate a petition on the internet calling for ‘a Global Whale Sanctuary by 2000’ which they hoped would catch the spirit of the new millennium; but the idea was dropped after the South Pacific Whale Sanctuary was turned down for the second time.

According to Sidney Holt (2000), ‘administratively speaking, it is difficult to see how [a world ocean sanctuary] would differ from the existing [IWC] moratorium [on whaling]. Both would be indefinite and require a three-fourths contrary majority to be over-turned. However, in the eyes of some, the idea of a sanctuary rather than an indefinite pause in commercial whaling may be weightier.’

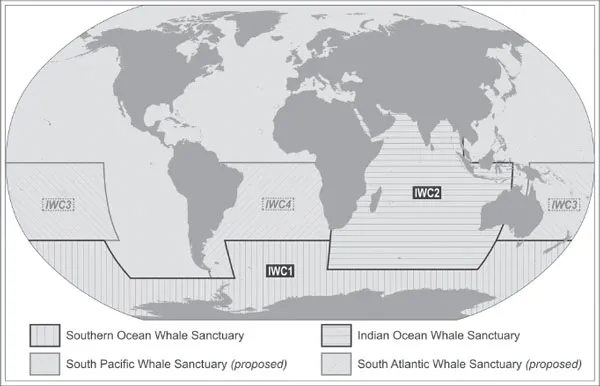

Another kind of cetacean sanctuary is the so-called ‘national sanctuary’ that some countries and territories have designated within their national waters, usually to the 200nm (370km) limit of the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) (see Table 1.2 and Figure 1.2). Many of these have come as part of the multinational effort to have the IWC turn the South Pacific into a whale sanctuary. The national waters and EEZs are so large in the Pacific Islands Region, with its sprawling island archipelagos, that, despite the IWC turning down the South Pacific Whale Sanctuary, more than half of the Pacific Islands Region is now covered by national cetacean sanctuaries (see Box 5.11, p316).

Table 1.2 Proposed and existing national EEZ cetacean sanctuaries

Source: research for this book and Hoyt (2005a); national sanctuary sizes are from the Sea Around Us Project (www.seaaroundus.org/eez)

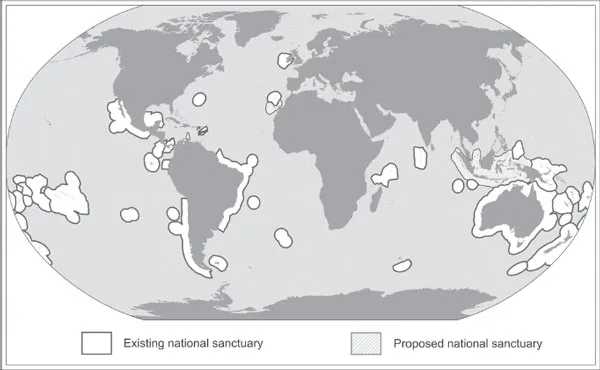

Figure 1.2 Map of national EEZ sanctuaries for cetaceans

Table 1.2 comprises a list of cetacean sanctuaries, both existing and proposed, that cover the national waters of a country or overseas territory. Since the late 1970s, 28 countries have declared their national waters as cetacean sanctuaries of one kind or another, three of which still have to finalize the legal declaration. Three additional proposals are yet to be approved. More information about each these national sanctuaries is provided under the specific marine region in Chapter 5 where the individual country or territory is found.

Neither the national sanctuaries nor the IWC sanctuaries, however, are considered marine protected areas by MPA practitioners, or under International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) definitions (IUCN, 1994; Dudley, 2008) (see Box 1.1). Neither type of sanctuary is as important for cetacean habitat conservation as smaller, carefully regulated and managed MPAs. To some extent, they are political declarations. A number of papers and reports have focused on the meaning and rationale behind these sanctuaries (e.g. Phillips, 1996; Holt, 2000; Leaper and Papastavrou, 2001; Carlson, undated). Still, these sanctuaries deserve recognition, discussion and efforts for enhanced protection.

Perhaps the hottest new area of marine conservation, and one of the most important for cetaceans, is the move to promote and create MPAs on the high seas (see Table 1.3). In 1999, the Pelagos Sanctuary for Mediterranean Marine Mammals (originally called the Ligurian Sea Sanctuary) was announced as the world’s first high seas MPA. Designated by France, Monaco and Italy and solidified by the Barcelona Convention, this landmark agreement covered 47 per cent national and 53 per cent international waters. It established a precedent for high seas MPAs which have since been proposed in other parts of the world ocean. More discussion of this will come later (see Case Study 3, p155). The Pelagos Sanctuary also serves as an important model for transboundary cooperation. Of course, transboundary, or transborder, protected areas have been a strong feature of land-based conservation for some decades, but they are fairly new at sea. A number of high seas MPA proposals include partially national waters and a transboundary component in part to garner broader support for potential designation. Besides Pelagos, high seas transboundary proposals include the Alborán Sea MPA and Specially Protected Area of Mediterranean Importance (SPAMI), Beringia Heritage International Park, Costa Rica Dome MPA, Saya de Malha Bank MPA and the Southeast Shoal of the Grand Bank MPA. Cooperation among countries both in a regional context, such as in the Mediterranean with Pelagos and the Alborán Sea proposal, as well as on the open ocean high seas, will be essential for the creation, management, enforcement and monitoring of high seas MPAs and MPA networks.

Box 1.1 IUCN management categories I–VI for protected areas (PAs), also applied to marine protected areas (MPAs)

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (Dudley, 2008), a protected area (PA) is defined as ‘a clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values’.

The various categories of protected areas – including land-based, riverine and marine protected areas – are further defined as follows.

Category Ia – strict nature reserves – are strictly protected areas set aside to protect biodiversity and also possibly geological/geomorphological features, where human visitation, use and impacts are strictly controlled and limited to ensure protection of the conservation values. Such protected areas can serve as indispensable reference areas for scientific research and monitoring.

Category Ib – wilderness areas – are usually large unmodified or slightly modified areas, retaining their natural character and influence, without permanent or significant human habitation, which are protected and managed so as to preserve their natural condition.

Category II – national parks – are large natural or near natural areas set aside to protect large-scale ecological processes, along with the complement of species and ecosystems characteristic of the area, which also provide a foundation for environmentally and culturally compatible spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational and visitor opportunities.

Category III – natural monuments or features – are set aside to protect a specific natural monument, which can be a landform, seamount, submarine cavern, geological feature such as a cave or even a living feature such as an ancient grove. They are generally quite small protected areas and often have high visitor value.

Category IV – habitat/species management areas – aim to protect particular species or habitats and management reflects this priority. Many Category IV protected areas will nee...