eBook - ePub

The Urban Housing Manual

Making Regulatory Frameworks Work for the Poor

- 150 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Urban Housing Manual

Making Regulatory Frameworks Work for the Poor

About this book

Red tape is a significant stumbling block to the provision of affordable shelter to the urban poor and, indeed, slums are largely the result of inappropriate regulatory frameworks. This practice-oriented manual tackles the issue of regulatory frameworks for urban upgrading and new housing development, and how they impact on access to adequate, affordable shelter and other key livelihood assets, in particular for the urban poor. It illustrates two methods for reviewing regulatory frameworks and expounds guiding principles for effecting change, informed by action research. The downloadable resources contain case studies, methods, exercises and tools, references and website links, and a video on reviewing regulatory frameworks.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Urban Housing Manual by Geoffrey Payne,Michael Majale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Regulation and Reality

The main challenge facing governments, the international community and civil society organizations involved in urban development and housing is to upgrade existing informal settlements and improve access to legal and affordable new housing

The Process of Urban Growth

Is urban growth in developing countries inevitable? Can it, or should it, be stopped, reduced or controlled, possibly by encouraging rural development programmes?

These questions have been asked of professionals, governments, researchers/academics and international agencies ever since developing countries began to experience a mass movement from rural to urban areas in the latter part of the last century.

Certainly, the scale of urbanization currently underway in developing countries is without parallel in human history. As United Nations (UN) statistics confirm (UN-Habitat, 2003a, p5), the world’s population has increased from 2.5 billion in 1950 to 6 billion in 2002, of which 60 per cent has been in the urban areas of developing countries. As if this did not in itself present a massive challenge to governments, civil society and the international community, the global urban population is set to increase by more than 2 billion within 30 years, while rural populations remain virtually static or, in some cases, begin to decline. The projected increase in population globally represents an annual increase of about 70 million people, all of whom will need land, housing, services and, most importantly, work, primarily in urban areas.

These global figures are matched by evidence from individual countries (see Table 1.1). For example, the populations of some cities are increasing at more than 7 per cent per year, which suggests their populations will double within a decade. Many others will see substantial numerical increases, even with lower percentage growth rates.

| Estimated and projected populations (millions) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2000 | 2015 | |

| Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire | 2.19 | 3.79 | 6.08 |

| Accra, Ghana | 1.38 | 1.87 | 2.89 |

| Ahmedabad, India | 3.25 | 4.43 | 6.61 |

| Cairo, Egypt | 8.29 | 9.46 | 11.53 |

| Dar es Salaam, Tanzania | 1.31 | 2.11 | 4.08 |

| Dhaka, Bangladesh | 12.52 | 22.77 | 6.62 |

| Jakarta, Indonesia | 7.65 | 11.02 | 17.27 |

| Johannesburg, South Africa | 2.08 | 2.95 | 3.81 |

| Lagos, Nigeria | 4.77 | 8.67 | 15.97 |

| Lima, Peru | 5.82 | 7.44 | 9.39 |

| Mexico City | 15.31 | 18.06 | 20.43 |

| São Paulo, Brazil | 15.10 | 17.96 | 21.23 |

Source: UN-Habitat, 2003a, Table C1

Of course, it is always dangerous to assume that the future will be simply an extension of the past, and many large cities have, in fact, grown at less than the forecast rates. Conversely, many smaller secondary towns are growing at faster rates than the major cities. While variations are common, it is nonetheless a fact that urban growth has been accelerating for the last few decades and shows no sign of stopping in the foreseeable future. Attempts to stop or control urban growth have proved expensive and ineffective, and are possibly incompatible with the principle of freedom of movement enshrined in most democratic constitutions.

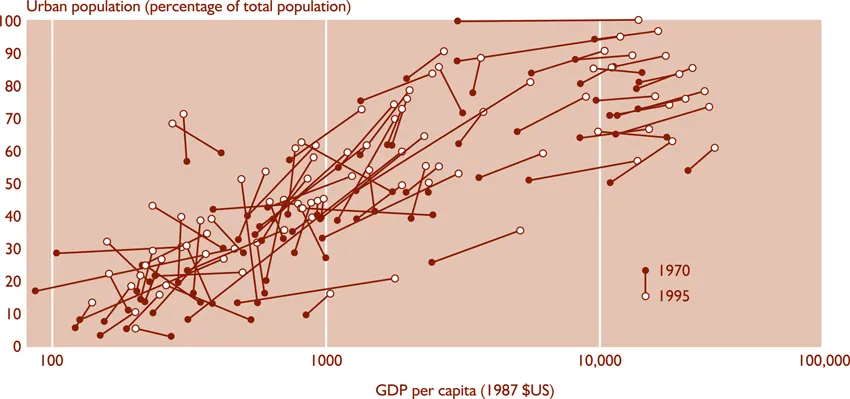

It is also important to remember that a high proportion of urban population growth is due to the natural increase of the existing population rather than rural–urban migration. Expanding rural development programmes would not, therefore, significantly reduce urban population growth rates. In addition, urban areas contribute a significant proportion of central government resources, including those for rural development, so healthy, dynamic urban areas are essential for national and regional development. Moreover, international data (eg UNCHS, 1996, p28; World Bank, 1999, p126) show a direct correlation between levels of urbanization and economic development, so that urban growth can broadly be associated with economic progress rather than decline (see Figure 1.1). The challenge is therefore how to manage the process of urban growth, rather than how to prevent or reduce it.

FIGURE 1.1 Urbanization is closely related to economic growth

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators, 1999, p126

The urbanization of poverty

One result of urban growth is the urbanization of poverty. A significant and increasing proportion of the growing urban populations are living on low incomes. For example, more than three-quarters of the poor in Latin America already live in cities, and many poverty-related problems – such as a lack of secure housing, or access to water and sanitation – tend to be more prevalent in urban than rural areas (UN-Habitat, 2001, p15). Current indicators, such as per capita incomes of less than a dollar a day, do not take into account the increased costs of living in urban areas and the difficulty of living outside the cash economy. While urban incomes, even for rural–urban migrants, are often substantially higher than those in rural areas, these higher living costs force the poor into spending a high proportion of their incomes on basic human needs, including food, water and housing. It has been estimated that nearly 1 billion urban residents in developing countries are poor, and their numbers are increasing more rapidly than in rural areas.

While the statistics are daunting, they do not convey the human dimension of the challenge. Every morning, nearly 1 billion people (UN-Habitat, 2003a, p14) wake up in insecure, substandard homes facing an uncertain day, let alone a future. Children are born into lives where clean water and healthy diets are unknown, and attending school is a dream beyond the reach of many. Economic deprivation puts family life under pressure and drugs, drink or gambling offer tempting, if temporary, escape routes for some. The vast majority, however, battle on from day to day, sacrificing their own lives in the hope of something better for their children.

Similar problems faced the urban poor in 19th-century Britain, when cholera epidemics and other diseases wiped out whole swathes of the urban populations before public health legislation ensured access to basic services and improved the environment. Even then, however, it took several decades before institutional capability developed sufficiently to raise standards that could be called adequate, despite Britain’s economic pre-eminence and the relatively small numbers of people involved. Given the far larger numbers and the limited human, technical and financial resources available to governments in developing countries, it is hardly surprising that they have been overwhelmed and are struggling to resolve their problems.

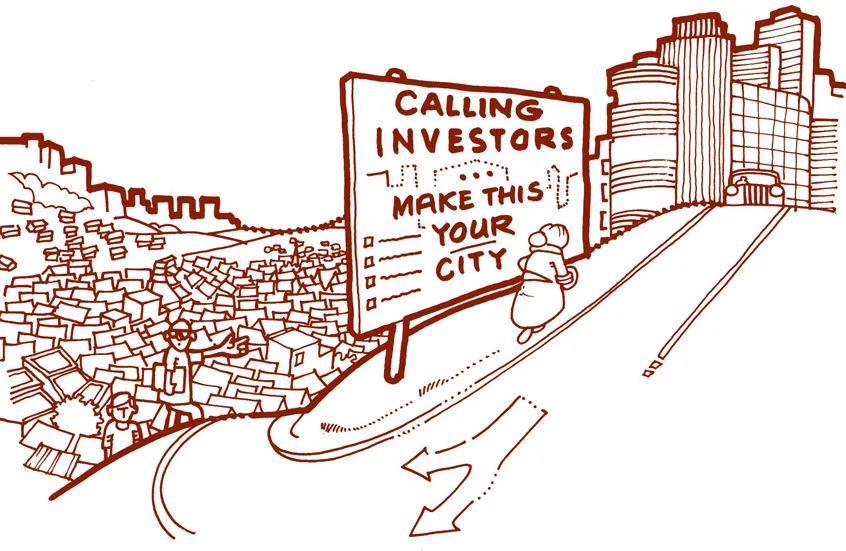

The growth of slums and informal settlements

Rapid urbanization and urban growth have placed immense pressure on the resources of national and local governments. Few have been able to meet the increasing need for planned and affordable land, housing and services either through direct provision or incentives to the private sector. The result is that millions of people around the world have found their own solution in various types of slums and unauthorized or informal settlements (see Box 1.1). Ironically, these often reflect the socio-economic and cultural needs of low-income communities more than the official forms of development favoured by professionals and government agencies.

Box 1.1 What is a slum?

A slum is a contiguous settlement where the inhabitants are characterized as having inadequate housing and basic services. A slum is often not recognized and addressed by the public authorities as an integral or equal part of the city.

Target 11 of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) describes typical slums in developing countries as ‘unplanned informal settlements where access to services is minimal to non-existent and where overcrowding is the norm. Slum conditions result in placing residents at a higher risk of disease, mortality and misfortune’.

A review of different slum definitions by UN-Habitat revealed the following attributes of slums:

- Lack of basic services.

- Substandard housing or illegal and inadequate building structures.

- Overcrowding and high density.

- Unhealthy living conditions and hazardous locations.

- Insecure tenure; irregular or informal settlements.

- Poverty and social exclusion.

Source: UN-Habitat, 2003a, p10

According to UN estimates there are at present 924 million people living in such settlements, which are also the most conspicuous manifestations of the urbanization of poverty (UN-Habitat, 2003a, p2). The number is expected to increase to 2 billion (2000 million) by 2030 unless major changes are made to the present policies and practices of urban management. This requires a dramatic increase in efforts to improve living conditions in existing slums and informal settlements, and to reduce the existing numbers down to modest levels. It also requires an acceptance that unless access to legal shelter is made more affordable and accessible to the majority of the urban poor, the growth of such unauthorized settlements will continue unabated. This is obviously not good news for the poor who have to endure substandard and, in some cases, subhuman living conditions on the margins of urban society. However, neither is it in the interests of the more fortunate affluent minority, since they will also be affected directly or indirectly by ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures, Tables and Boxes

- About the Authors and Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Section 1: Regulation and Reality

- Section 2: Regulation and Regulatory Frameworks

- Section 3: How do Regulatory Frameworks Affect the Urban Poor?

- Section 4: Reviewing Regulatory Frameworks

- Section 5: Guiding Principles for Effecting Change

- Section 6: Some Final Suggestions

- Endnotes

- References and further reading

- Index