![]()

1

Flood Hazards, Vulnerability and

Risk Reduction

Roger Few

Introduction

Flooding is one of the most frequent and widespread of all weather-related hazards. Floods of various types and magnitudes occur in most regions of the globe, causing huge annual losses in terms of damage and disruption to economic livelihoods, businesses, infrastructure, services and public health. Long-term data on disasters suggest that floods and wind storms (which frequently lead to flooding) are by far the most common causes of natural disaster worldwide. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies reports that, in the ten years from 1993 to 2002, flood disasters ‘affected more people across the globe (140 million per year on average) than all the other natural or technological disasters put together’ (IFRC, 2003, p179). Further EM-DAT data collated by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) indicate that this numerical dominance continued through 2003 and 2004.

In order to set the book's detailed discussions on health and flooding in context, this chapter provides a summary of the nature of floods and flood hazard now and in the future, a conceptual background to the analysis of flood risk, and an overview of some generic issues relating to flood risk reduction and hazard response. The chapter first describes the causes, types and variability of flood events, discussing recent trends in the incidence of flood hazard and disaster, and current understanding of the potential increased threat of flooding that may arise as a result of climate change. It then outlines theoretical insights from broader analysis of hazard and risk, discussing the concepts of vulnerability, coping capacity and adaptation. The final section provides generic information on overall response to flood hazards, including the balance between structural and non-structural mitigation, the importance of flood preparedness and the role of internal and external agents in flood risk reduction and emergency relief.

Floods and flood hazard

As Parker (2000) discusses in detail, floods can take many forms and it is not easy to pin down a precise definition for the term. Broadly speaking, however, and in the context of this book, a flood refers to an excess accumulation of water across a land surface: an event whereby water rises or flows over land not normally submerged (Ward, 1978). Floods can originate from a variety of sources, and Table 1.1 provides a simplified typology of the principal causes and associated flood types.

The leading cause of floods is heavy rainfall of long duration or of high intensity, creating high runoff in rivers or a build-up of surface water in areas of low relief. Rainfall over long periods may produce a gradual but persistent rise in river levels that causes rivers to inundate surrounding land for days or weeks at a time. In August 2002, for example, intense rainfall of long duration induced extreme flooding spanning five countries of Central and Eastern Europe (Caspary, 2004). Intense rain from storms and cyclones, on the other hand, may produce rapid runoff and sudden but severe flash floods across river valleys. The flooding from these events is typically more confined geographically and persists for shorter periods; but the violence of the event can be highly damaging and dangerous. Intense rain can also cause standing water to develop in urban areas when the capacity of storm drain systems is exceeded.

Table 1.1 Causes of floods

| Cause | Examples of flood types |

| High rainfall | Slow-onset riverine flood

Flash flood (rapid onset) Sewer/urban drain flood |

| |

| Tidal and wave extremes | Storm surge

Tsunami |

| |

| Thawing of ice | Jökulhlaup

Snowmelt |

| |

| Structural failure | Dam-break flood

Breaching of sea defences |

Source: adapted from Parker (2000)

Coastal areas may face an added threat from the proximity of the sea. Tidal and wave extremes are another major cause of floods, bringing seawater across land above the normal high tide level. Cyclonic storms may create a dangerous storm surge in which low atmospheric pressure causes the sea to rise and strong winds force water and waves up against the shore. Tsunami waves originate from the displacement of water during undersea earthquakes and other massive disturbances such as landslides. They may have tremendous destructive power, as witnessed by coastal communities in 11 countries that were struck by the devastating Indian Ocean Tsunami of December 2004.

Other causes of severe flooding include rapid releases of water from snow-fields and glaciers – a phenomenon known as jökulhlaup in Iceland where volcanic action beneath glaciers has produced highly destructive floods. Structural failure or overtopping of artificial river dams and sea defences may also result in damaging flood events. It is important to note further that flood causes may combine (Parker, 2000). For example, winter storms in North-West Europe may produce simultaneous inland flooding and storm surges that doubly afflict coastal areas adjacent to river mouths.

Flood events vary greatly in magnitude, timing and impact. Handmer et al (1999, p126) note that the term flooding can cover ‘a continuum of events from the barely noticeable through to catastrophes of diluvian proportions’. There are a number of measurable characteristics through which events can be differentiated, including flood depth, velocity of flow, spatial extent, content, speed of onset, duration and seasonality (Parker 2000; Few, 2003). Floods may vary in depth from a few centimetres to several metres. They may be stationary or flow at high velocity. They may be confined to narrow valleys or spread across broad plains. They may contain sewage and pollutants, debris or such quantities of sediment that they are better termed mudflows. They may be slow to build up or rapid in onset as in flash floods. They may last from less than an hour to several months.

Floods may also be associated with regular climatic seasons such as monsoon rains and other annual heavy rainfall periods. In some locations, such as the major floodplains of Bangladesh, extensive flooding from seasonal rains is an expected annual occurrence to which human lifestyles and livelihoods are largely (pre) adapted (though such predictable flooding may still have health implications). However, seasonal flood levels vary from year to year, and such areas tend to be subject to occasional flood events that exceed the normal range of expectation. In 1998, Bangladesh experienced flooding of an unprecedented magnitude (depth and duration), surpassing the previous record flood that occurred in 1988 (Nishat et al, 2000). In 2004, the country was hit once again by floods of an equivalent scale (Alam et al, 2005).

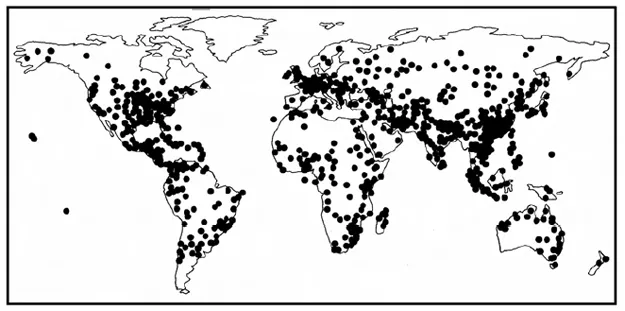

Figure 1.1 indicates the distribution of extreme flood events during the period 1990 to 2004, drawing mainly on flood mapping data provided by the Dartmouth Flood Observatory. Severe floods from high rainfall (of long or short duration) have occurred in almost all the humid regions of the world, with flash floods also affecting many drier zones. Extreme flooding from wind storms and other causes tends to be more concentrated in distribution.

Figure 1.1 Locations of extreme flood events 1990–2004

Note: This map should be regarded as indicative only since there is no standard definition of what constitutes an extreme event. A depiction of all flood events of different magnitudes during this period would show an even wider distribution.

Source: developed from maps and data produced by Dartmouth Flood Observatory, Hanover, US, www.dartmouth.edu/~floods, and by EM-DAT: Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA)/CRED International Disaster Database, Universite Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium

Hotspots for tropical storms (known as cyclones, typhoons or hurricanes) lie around the Bay of Bengal, the western Pacific coasts, the Caribbean and southeastern US. Tsunamis historically have been associated mostly with the Pacific Ocean, although by far the most destructive event of recent years took place in the Indian Ocean in 2004. Floods associated with thawing of ice and snow occur predominantly in northern latitudes or in mountainous regions (note that there is likely to be an under-reporting of extreme flood events in sparsely populated regions, including the far north of Canada and Russia).

River and coastal defence engineers distinguish flood events using a statistical flood frequency measure, which uses historic data to define the probability of occurrence of a flood event of a given magnitude (Parker, 2000). Hence a 100-year flood refers to an event of a size likely to occur once in every 100 years, while a one-year flood might be expected annually. However, the physical parameters of a flood are not always effectively measured and are not necessarily reliable indicators of its impacts. Differing perceptions of and terminology for flood severity make it difficult to develop a standardized categorization of floods, and no such detailed categorization is attempted here. In any case, categorizing by flood magnitude can be misleading when considering severity of impacts since the same flood may differ in its effect at even an inter-household scale (Wisner et al, 2004).

The consequences of flooding are by no means solely negative. Seasonal river floods, in particular, play a crucial role in supporting ecosystems, renewing soil fertility in cultivated floodplains (Wisner et al, 2004). In regions such as the floodplains of Bangladesh, a ‘normal’ level of seasonal flooding is therefore generally regarded as positive: it is only when a flood reaches an abnormal or extreme level that it is perceived negatively as a damaging event (Parker, 2000).

It is this latter sense in which we use the term flood hazard in this book, meaning a flood event with the potential to cause harm to humans or human systems. In this conception, a flood event is a physical phenomenon, but a flood hazard is inherently ‘social’. A flood event only constitutes a flood hazard when it threatens to have a negative impact on people and society (hence a river flood in an uninhabited area does not, for the purposes of this book, constitute a hazard). Flood hazards may, of course, have varying degrees of impact, from minor or small-scale damage to damage of catastrophic proportions. This book is concerned with all scales of impact because all forms of flooding can pose health risks. However, in public perception at least, it is flood disasters that tend to be of special concern.

Flood disasters

The definition of what constitutes a disaster is another contentious issue; but in its most basic sense it is used to describe an event that brings widespread losses and disruption to a community. Some definitions include the notion that it exceeds the ability of that community to cope using its own resources (ISDR, 2002; White et al, 2004). A number of studies and reports discussed in this book refer to flood disasters of different scales, and statistics on flood disasters provide a useful indicator for global flood risk.

We have already referred to the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED), which manages a global database on disaster impacts known as EM-DAT. CRED classifies an event as a disaster if at least one of the following has occurred: 10 or more people killed; 100 or more people reported affected; a call for international assistance; and/or a declaration of a state of emergency. According to their disaster data, floods come second only to drought/famine during recent years in causing direct mortality (as defined) and account for more than half of all people affected by natural disasters. Since ‘people affected are those requiring immediate assistance during a period of emergency, i.e. requiring basic survival needs such as food, water, shelter, sanitation and medical assistance’ (IFRC, 2003, p180), this measure provides an indication of the scale of health impacts associated with flooding.

Though they have a number of limitations regarding the quality of information (see Chapter 2), disaster statistics also provide some indication of the geography of flood risk to human populations. Tables 1.2 and 1.3 compile flood and wind storm disaster statistics for different continents using the EM-DAT data from CRED (many of the deaths and other impacts attributed to wind storms are flood related). From the tables, it is clear that flood disasters and their mortality impacts are heavily skewed towards Asia, where there are high population concentrations in the floodplains of major rivers, such as the Ganges-Brahmaputra, Mekong and Yangtze basins, and in cyclone-prone coastal regions, such as around the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea, Japan and the Philippines. Asia accounts for 98 per cent of all people affected by flood disasters and 90 per cent of all people affected by wind storms during the period 1990 to 2004.

Table 1.2 Flood disasters by continent, 1990–2004

| Continent | Reported disastersa | People reported killed | People reported affected |

| Africa | 319 | 11,223 | 23,058,000 |

North America and the

Caribbean | 130 | 4171 | 2,623,000 |

Central and South

America | 239 | 35,459 | 9,822,000 |

| Asia | 558 | 63,661 | 2,047,739,000 |

Europe and Russian

Federation | 272 | 3542 | 9,204,000 |

| Oceania | 44 | 46 | 264,000 |

| Total | 1562 | 118,102 | 2,092,710,000 |

Note:a There may be some double counting in this column since the regional statistics are aggregated from data on flood incidence per country (and some large-scale events may affect more than one country at a time).

Source: EM-DAT: OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database, Université Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium

Deaths from floods and wind storms are also notably high in Central and South America, where the impacts of two major events – Hurricane Mitch in Central America in 1998 and floods in Venezuela in 1999 – dominate the figures. It is important to note that specific events can have a major effect on regional disaster statistics. Other catastrophic events that strongly skewed regional figures upward were two major flood events in Haiti in 2004 and an enormously destructive cyclone disaster in Bangladesh in 1991. Extreme wave and surge events are not indicated in Tables 1.2 and 1.3, but the equivalent EM-DAT data in this category are dominated by the single tsunami event of 2004.

Table 1.3 Wind storm disasters by continent, 1990–2004

| Continent | Reported disastersa | People killed | People reported affected |

| Africa | 85 | 1939 | 7,217,000 |

| North America and the Caribbean | 328 | 7132 | 16,636,000 |

| Central and South America | 93 | 20,215 | 5,790,000 |

| Asia | 497 | 190,940 | 358,965,000 |

| Europe and Russian Federation | 137 | 1293 | 7,646,000 |

| Oceania | 103 | 376 | 4,746,000 |

| Total | 1243 | 221,895 | 401,000,000 |

Note:a There may be some double counting in this column since the regional statistics are aggregated from data on flood incidence per country (and some large-scale events may affect more than one country at a time).

Source: EM-DAT: OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database, Université Catholique...