![]()

1

Locating theory in research

Opening a conversation

John Quay, Jennifer Bleazby, Steven A. Stolz, Maurizio Toscano and R. Scott Webster

Correspondences between researching and catering

This introductory chapter is specifically intended to support those newer to research, such as graduate researchers, by offering a propaedeutic – a teaching orientated introduction – to help scaffold a way into the multifaceted conversation about theory and research that unfolds in the chapters to come. For this reason, we have designed the first chapter around a series of analogies between researching and catering. It may appear incongruous to bring researching – which most would consider to be a highbrow and specialized enterprise – together with the seemingly commonplace, everyday task of catering a shared meal. However, this everydayness is valuable because it supports the notion of “‘carrying over’ – metapherein” (Arendt, 1978, p. 103) from something familiar to something seemingly more complex. The resulting juxtaposition assists in making visible what is commonly taken for granted. Positioning both researching and catering as inquiries, and drawing correspondences between them on this basis, supports improved comprehension of the nature of researching and specifically the place of theory in education research.

We begin where we believe many graduate researchers begin: in their confrontation with the specialized and sometimes technical aspects of the task of doing research.1 However, we do not mean to convey that either researching or catering are merely mechanistic, which may sometimes be assumed when the notion of a “recipe” is used. Both catering and researching involve much more than mechanical steps prescribed by instructional procedures. Our position here will become clearer as the chapter progresses to its conclusion, leading into the broader conversation about the place of theory in research that makes up the bulk of this book.

The first section of this chapter expands on the analogy by highlighting correspondences between the tasks and materials involved in researching and catering. The aim here is to raise awareness of the complexities that lie beneath a technical orientation. These complexities illuminate the presence of three levels of inquiry – inquiries within inquiries within inquiries – debunking the notion that either researching or catering are simple and straightforward procedural undertakings. This section is, of course, itself underpinned by a particular theoretical perspective articulated in greater detail elsewhere (see Quay, 2013, 2015).

The second section of this chapter delves deeper to unfold this perspective in relation to some of the intricacies that characterize these complexities of inquiry. In doing so, this section brings together the philosophical work of Charles S. Peirce and John Dewey, both steeped in the pragmatic tradition. We note that other theorists could just as readily be employed here to offer a different understanding of the logic of inquiry and challenge or support the position we have articulated. However, we have chosen to privilege the pragmatic perspectives of Peirce and Dewey in this circumstance because we consider their work to proffer important insights regarding the nature of both theory and inquiry.

The first and second sections lead from a concern with the complexities and intricacies of inquiring to the much broader question of how judgments are made within inquiring. In this way, the third section of this chapter, itself founded in a further theoretical perspective, illuminates the importance of comprehending the way theories situate ideas and practices historically, geographically, philosophically and politically – thus predisposing judgment. As Karl Popper argued, “there are no uninterpreted visual sense data, … whatever is ‘given’ to us is already interpreted, decoded” (1976, p. 139). Theories are, after all, human creations. Applying our culinary analogy, judgments made through inquiring are responses based on particular “tastes” that must be acknowledged and explained. “Theory here, then, refers to the articulation of the framework of beliefs and understandings which are embedded in the practice we engage in” (Pring, 2015, p. 96). Locating theory in research is not a matter of finding a needle in a haystack, but rather of understanding how every aspect of researching is imbued with theory.

This third section of the chapter is perhaps the most important, as it highlights how arguing for the place of theory in inquiry is itself a theoretically framed endeavor, thus segueing into the conversation on theory and research that comprises the remainder of the book. We acknowledge without reservation that theoretical positions frame the way we have presented all sections of this chapter, evoking certain theoretical perspectives. No account is of itself so universal that it could not be challenged or supported by way of other theoretical frameworks, as Thomas Kuhn (1970) so eloquently emphasized in his exploration of scientific revolutions.

Complexities of researching and catering: primary, secondary and tertiary level inquiries

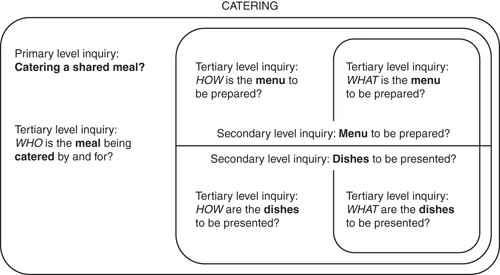

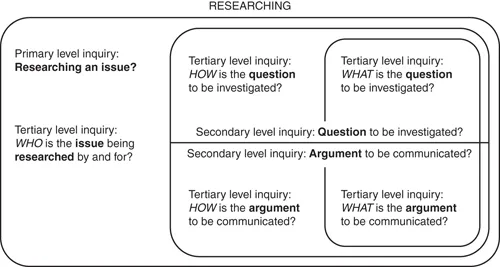

A closer look at the act of catering a shared meal for family or friends reveals that what may appear to be a singular inquiry is actually a primary level inquiry comprised of two interdependent secondary level inquiries. The primary level inquiry of catering a shared meal is comprised of both preparing the menu, including choice and cooking of dishes, as well as presenting the dishes, including plating and serving of the dishes. Applying our analogy, the primary level inquiry of researching an issue can be seen to be comprised of two secondary level inquiries: one is focused on investigating the question that pinpoints this issue, while the other is focused on communicating the argument that is developed via investigation of this question. The shift from question to argument, from investigating to communicating, corresponds with the shift from preparing the menu to presenting the dishes. The extent of this shift is revealed in some of the basic features of each secondary level inquiry which, when juxtaposed, further highlight correspondences between researching and catering (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Correspondences between catering and researching at the very basic level of tasks and materials, highlighting the presence of two secondary level inquiries within a primary level inquiry.

| Catering a shared meal | Researching an issue? |

| Menu to be prepared? | Question to be investigated? |

| Cooking procedures (integrated recipes with detailed accounts of preparation for multiple dishes, including ingredient sourcing and cooking, that is reproducible) | Research methods (detailed accounts of data collection and analysis procedures that are reproducible) |

| Cooking techniques (e.g., searing, marinating, poaching) | Research techniques (e.g., participant observing, interviewing, structural equation modeling, videoing) |

| Cooking ingredients – need to be sourced and worked with (e.g., field mushrooms) | Data – need to be collected and worked with (e.g., online survey responses) |

| Cooking tools/equipment (e.g., utensils, oven, saucepans) | Tools/equipment (e.g., research hardware such as measuring and recording equipment, research software such as NVIVO) |

| Dishes to be presented? | Argument to be communicated? |

| Table and room settings for dining (e.g., formal, casual, buffet) | Document forms (e.g., thesis, report, article) |

| Plating techniques (e.g., classical, landscape, finger foods, sharing platters) | Writing/formatting/referencing styles (e.g., Harvard, APA, Chicago, Oxford) |

It is important to note that the two secondary level inquires actually inform and shape each other. They are not merely distinct steps in a sequence. Investigation of a question already involves considering the generation of an argument and communication of this argument. Furthermore, as we think about the argument in more detail we may also redefine the initial question. Question and argument co-inform each other. The same can be said for preparation of a menu and presentation of the dishes. Our choice of menu informs the way we plate and serve the dishes and vice versa. For example, we may reconsider our decision to make soup when we realize we don’t have enough soup bowls for everyone.

What, how and who questions

Digging deeper reveals a further tertiary level of inquiry, denoted by three question types: what, how and who questions (see Figure 1.1).2 Each secondary level inquiry is informed by these three interrelated questions. Most obvious is how both secondary level inquiries involve what and how questions: “What is the …?” and “How is the …?”. These questions articulate the particular tertiary inquiries that constitute the main elements of each secondary level inquiry. In preparing a shared meal, these may be: “What is the menu to be prepared?” and “How is the menu to be prepared?”, followed by “What are the dishes to be presented?” and “How are the dishes to be presented?”. When researching, these equate to: “What is the question to be investigated?” and “How is the question to be investigated?”, followed by “What is the argument to be communicated?” and “How is the argument to be communicated?”.

Figure 1.1 Catering and researching, illuminating primary, secondary and tertiary level inquiries and the what, how and who questions informing them.

A further tertiary level question is focused on “Who …?”. This question emphasizes the context within which the research or catering is taking place, characterized by the needs and interests of particular groups of people. In catering, the who question can be articulated for each secondary level inquiry: “Who is the menu being prepared by and for?” and “Who are the dishes being presented by and for?”. For example, one might ask questions like: “What dish can I prepare for my vegan, gluten-intolerant friend who is coming to dinner?”, “Should I use penne pasta instead of spaghetti and cut the meatballs into small pieces so it’s easier for the baby to eat?”, “Can I just use readymade gravy since I’m no good at making it myself or can I get someone else to make this part of the meal?”. These questions show the prevalence of “who” in catering deliberations. In researching we ask analogous questions, such as: “Who does the issue affect and what are their needs and interests (e.g., school students, parents, teachers, curriculum developers, teacher education providers, governments, society at large)?”. We also need to ask: “Who is the issue being investigated by and what relevant skills and knowledge do they possess?”. This is closely related to another question: “Who needs to be involved in the investigation of the issue and communication of the argument – that is, who should collaborate?”. For example, if the research could be improved by the collection of quantitative data and I have little expertise in this methodology, I may want to collaborate with a statistician or, perhaps, adjust my research focus so that the project can be completed to a high standard without the collection of such data. Other important “who” questions are: “Who is communicating the argument and to whom is it being communicated?” and “How can it be communicated in such a way that it will persuade this particular group of people?”.

These various questions, discerning “Who …?” at the secondary level of inquiry, come together at the primary level of inquiry: “Who is the meal being catered by and for?”. In researching it is similar, with the primary who question asking: “Who is the issue being researched by and for?”. This who question reveals how the secondary level inquiries come together as the one primary inquiry via the needs and interests of particular groups of people. These groups together constitute the broad community of stakeholders involved in any researching or catering project.

To elaborate, all research involves a situation or a project, wherein a range of people have a stake in resolving a shared issue – for example, a research project seeking funding to resource it. Here a group of researchers, often organised as chief and partner investigators, including doctoral candidates and supported by research assistants, will develop a funding submission that articulates an issue to be researched via investigation of a specific question or questions. This submission may involve input from others beyond the core research team who have a stake in this issue, others who are not researchers per se, widening the range of people identified in the submission. This is important as the question must appeal to a funding body, such as a government department or a philanthropic organisation, as expressive of an issue which they believe is of enough concern to their constituents that it is worthy of funding in a competitive process. The research team must also convince the funding body that, as a team, they possess all the skills and knowledge needed to effectively co...