- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1984. This book is an expansion of three lectures on schema theory given at the University of Alberta in the fall of 1983 as part of the MacEachran Memorial Lecture Series.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stories, Scripts, and Scenes by J. M. Mandler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Types of Mental Structure

What do stories, scripts, and scenes have in common? Superficially they concern widely different aspects of our experience. Stories are literary expressions that we read or hear; they often refer to times long past or to imaginary worlds. Scripts, in psychological parlance, represent the familiar, everyday events which fill our daily lives: trips to the grocery store, getting up in the morning, going to work—the routines of our workaday world. Scenes, of course, represent places, the rooms and streets and buildings in which our daily routines take place. In spite of the variety of experiences that stories, scripts, and scenes represent, when we examine the structure of these domains we find that they have much in common and result in common types of psychological processing. The commonalities reside in the fact that ail are represented in the human mind by related schematic forms of organization.

The use of schema theory has become widespread in psychological research. The phrase itself is perhaps misleading, since no one has yet developed a coherent schema theory for any domain. A more accurate phrase might be schema framework, since the principles subsumed under this view of the mind consist of very general beliefs about how this form of organization works. To reach the status of theory requires testability and especially falsifiability, and it is not clear that any specific schema theory has yet reached that pinnacle of science. Even the broad principles themselves need to be explored and sharpened, and most vitally, to be made explicit. This book represents a small step in that direction. In particular, I wish to examine the three domains of stories, scripts, and scenes with two purposes in mind. First, I wish to lay out what we do and do not know about the structure, or organization, of these kinds of knowledge. Second, I wish to explore the implications of schematic structure for processing, both encoding and memory, to see if there are unique processing principles associated with schematic organization.

I will concentrate first and most extensively on stories, because we have a more complete description of the organization of a story schema than we yet do of scripts or scene schemas.1 Even when our structural descriptions are well in hand, however, I reiterate we are still far from a schema theory, since those descriptions must be mapped in detail onto all the kinds of processing that we engage in when we experience a particular domain.

In this first chapter I delimit the reach of schema theory and contrast schematic structures with other forms of organization. Since so many psychologists work under the rubric of schema theory and use the term to indicate the organization of many different kinds of knowledge, it is important to be clear that I am considering what may be only a subset of possible schematic forms—namely, those that involve spatio-temporal relationships. After introducing schematic structure, I consider story structure in some detail. In the second chapter I discuss the various levels at which a story schema operates and their implications for processing. In the last chapter I extend these notions to scripts and scenes, followed by a general discussion of schema theory as a whole.

Some psychologists use the term schema as the basic building block of cognition (Rumelhart, 1980b; see also G. Mandler, 1984). On this view all mental organization is schematic in nature. Our knowledge about an object or classes of objects, about an event or classes of events, about personality traits and social norms, can all be considered as small networks of information that become activated as we experience these things and that function according to certain schematic principles. This view is a perfectly reasonable one. But for purposes of understanding the details of how such information is structured, it may be overly general. At present we simply do not know whether our knowledge in each of these domains is organized in a similar fashion and has similar consequences for processing. We do know that there are other forms of knowledge that do have different consequences for processing. For example, our representation of the alphabet is serially organized, with restrictions on points of access and on the rate at which we can produce various portions of it (Klahr, Chase, & Lovelace, 1983). Some of our knowledge about objects is organized into categorical (taxonomic) systems. Although we know many other things about animals, for instance, than their class membership, we have a representation of the animal domain that is organized in a hierarchical class-inclusion system. The way that we access information from such a system has different characteristics from a serial organization, or, I believe, from a schematic spatiotemporal one. For instance, there are differences in recall of categorically related and schematically related materials (Rabinowitz & Mandler, 1983). There are undoubtedly many other forms of organization; for example, Broadbent, Cooper, and Broadbent (1978) found characteristic differences in the ways in which people process matrix organizations and categorical ones.

In addition to spatio-temporal schemas there are motor procedures of all sorts that have also been called schemas (e.g., Piaget, 1952; Schmidt, 1975) but which seem to have a different kind of organization. There are also abstract characteristics of thinking and problem-solving that Piaget considered to be schemas, such as the concrete operational schema of seriation or the formal operational schemas of proportions and the isolation of variables. The latter forms of knowledge range from specific kinds of understanding, as in the case of a schema of proportions, to what appear to be general heuristics for certain kinds of problem solving, as in the case of the schema for the isolation of variables.

What are we to do with this welter of terminology and widely varying notions about what constituents a schema? My current solution is to narrow the scope of the discussion and to concentrate on the structures that organize our spatial and/or temporal knowledge about objects, events, and places. This is not to deny that other kinds of knowledge may have similar structures, but in many cases we know little about their organization. Further, the similarities that are found in processing across various domains may reflect general characteristics of organization, rather than of schematic organization per se. For example, in a seemingly straightforward extension of schema theory from its application to the representation of familiar event sequences (scripts), Graesser (1981) has suggested that the same principles apply to our understanding of personality traits and that they influence our encoding and memory for the personal characteristics of others in the same ways.2 He may be correct, but at the moment we have little notion as to how knowledge of personality traits is organized. So it is difficult to know whether the commonalities in processing information about events and about people's traits are due to a common form of organization or to the general properties any organized representation is apt to have.

To illustrate, Graesser and his colleagues (e.g., Graesser & Nakamura, 1982) have emphasized the role that schemas play in controlling memory for typical and atypical events. I discuss this aspect of schematic processing in some detail in chapter 3, but suffice it to say here that atypical events are usually better recognized (and under some circumstances better recalled) than typical ones. Friedman (1979) has found the same phenomenon in recognition of scenes. At first glance this would appear to indicate a commonality of schematic organization for events and scenes, and I have made that assumption (Mandler, 1979). But the same phenomenon is found for recognition, and in some cases, recall of low frequency (atypical) words in lists of unrelated nouns (Gregg, Montgomery, & Castano, 1980; Mandler, Goodman, & Wilkes-Gibbs, 1982). I think we would not want to say that lists of words, drawn from our vast vocabulary, have a schematic organization. In other words, if typicality effects on memory are a ubiquitous aspect of processing, they may not by themselves tell us anything specific about schemas. We may have to look at such phenomena in detail if we are to discover characteristic differences in processing due to particular kinds of organization.

Categorical Structure

The chief characteristic of a categorical (taxonomic) structure is that it consists of a class-inclusion hierarchy. To use the animal domain again, it can be classified into a number of exclusive branches, in which a particular animal is a member of each of the higher nodes on that branch and of no others. The basis of membership in a given category on a given branch of the tree is similarity. The similarity may be of form or function or of other types, but there must be some common (similar) principle that forms a relation among the members sufficient to group them together. Similarity, of course, was one of Aristotle's two associative principles, the other being spatial or temporal contiguity. Thus, one of the primary distinguishing characteristics of a categorical structure, in contrast to a schematic one, is that the relational "glue" that holds items together is similarity rather than contiguity.

There are many kinds of similarity relations and therefore many ways to form a classificatory hierarchy, whether of animals or of other things. For an animal taxonomy we can use reproductive characteristics, the presence or absence of vertebrae, degree of domestication, and so forth. Interestingly, I know of no discussion of how these various hierarchies are related to each other. The same animal moves from branch to branch of the various trees that result when we use different similarity criteria to make a classification system. Typically, when we wish to consider several independent criteria at once, such as classifying animals in terms of size and ferocity, we move to a matrix structure, which is characterized by class-intersection, rather than class-inclusion, relations.

One characteristic of taxonomic structures, then, is that they are highly flexible, in the sense that most things can be classified in many ways. Which aspect of an item we focus on during processing is a function of many variables—task demands, motivation, presence of related items in the vicinity, and so forth. The multiplicity of relations that can be used for categorizing things makes for great richness and flexibility in our thought, but it also means that any one aspect is apt to be used somewhat unpredictably during the encoding or retrieval process. To take the familiar example of studying and recalling a categorized list of words, unless subjects are told in advance what the organization of the list is, they will not know how to categorize the word apple, for instance, until they have seen other words on the list. Apple might belong to a category of foods, joined together with beef and broccoli, or to a category of fruit, joined with pear and grape, or to a category of red things, joined together with stoplight and fire engine.

In this sense the use of a categorical structure is optional and not a necessary part of encoding or retrieval. If you do not tell people about the organization of a list, or if you do not tell them to memorize it (if you do, adults at least will usually find the organization you have in mind), they will be less likely to find or use the organization. Recall, as a result, will be less complete.

Still another characteristic of taxononuc or categorical organization is the lack of principled relationships among the members of a given class. Each member is only guaranteed to have one relation to the other members, and that is the vertical relationship in the hierarchy of class inclusion. Other relations among items vary from member to member in idiosyncratic ways. That is, the links among individual members of a given class are apt to consist of relations stemming from the intersection of the particular taxonomy with other types of classification. For example, within a class of four-legged mammals, a lion and an antelope might be related by country of origin, an antelope and a cow by their herbivorous nature, a cow and a pig by their domestic nature, and so on. Hence, the only consistently reliable retrieval cue in a taxonomic hierarchy is the single link with the superordinate class in which members are included.

This kind of organization, in which items in a given node in the hierarchical structure are not consistently related to each other but solely to the next higher node, places restraints on retrieval. Because of the lack of principled links among members of a given class, most models of recall for categorized lists have assumed a probabilistic character. A category is entered via the superordinate link and a category member randomly chosen. Other members are retrieved in a probabilistic fashion (presumably because of the many idiosyncratic connections just discussed). Most models of category search have used a stop rule based on the ratio of the items that have been recovered to the number remaining (e.g., Graesser & Mandler, 1978). Since sampling with replacement is also assumed, as this ratio becomes larger there are an increasing number of failures to find a new item (Rundus, 1973). This type of retrieval process results in a negatively accelerated curve in the rate of retrieval of new items.

Associated with this sort of retrieval process is the phenomenon of output interference (Slamecka, 1972). Retrieval of one item from a category (or being given an item) inhibits recall of other items from the category. This phenomenon can be most easily explained by assuming independence of the items from each other, with the only direct connection being that to their common superordinate (Crowder, 1976; Roediger, 1974). Thus, retrieval from a categorical organization is thought to depend upon the particular form of the representation. The organization is a class-inclusion hierarchy and the only links due to the organization itself are the vertical ones between subordinate and superordinate classes.

Relatively little is known about the extent to which such a representation controls encoding. However, it appears that under many circumstances categorical information is not automatically used to organize input. Presumably some categorization goes on as an automatic part of perception, but in daily life we do not typically encounter categories of things as neatly arranged as they are in the categorized list of words studied in the laboratory. We sit on a piece of furniture, write with an instrument, get up and go to a kind of room, get in a vehicle, drive to a public building, and so on. Each of the individual objects with which we deal (chair, pen, garage, car, restaurant) may activate its immediate superordinate, but the sequential schematic structure in which these items are embedded is both more salient and more powerful in its effects on memory. I document this claim in the succeeding chapters; for the moment I want to consider a little more thoroughly the conditions that activate a categorical organization.

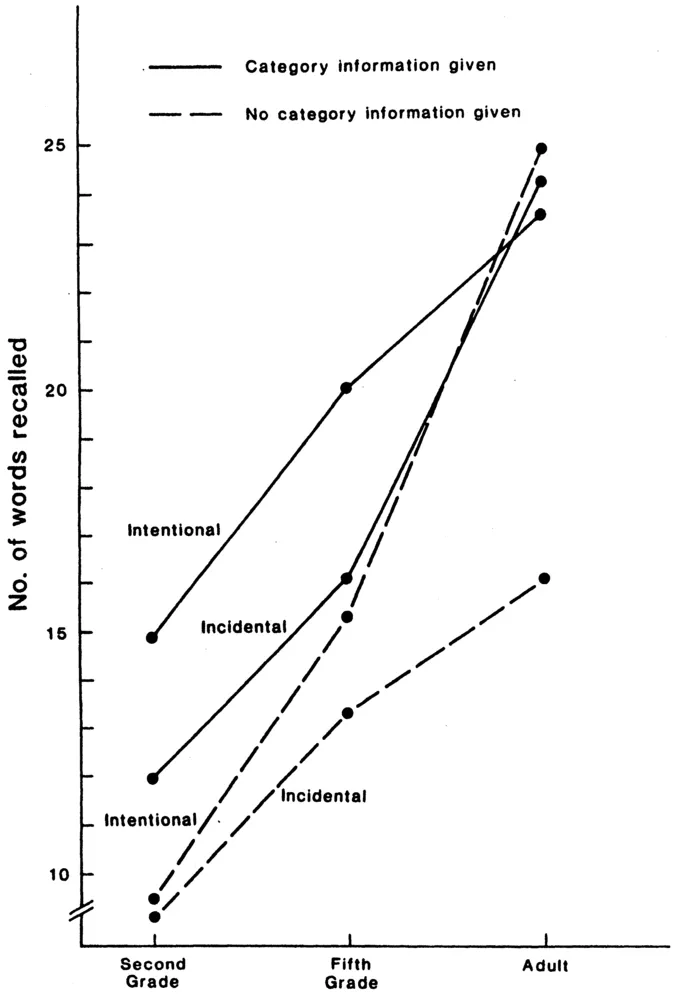

In an unpublished experiment from my laboratory, conducted with Matthew Lewis, we investigated the conditions under which people would discover and use the categorical organization of a list of pictures of common objects. The list consisted of five categories of six items each; the items were chosen to be among those most commonly generated by children. Subjects were second and fifth graders as well as adults. Both instructions and task were varied. Either the subjects were told to memorize the list or not; that is, they were in either an intentional or an incidental memory condition. Within each of these conditions subjects were either informed about the categorical structure of the list or not. Subjects in the intentional-informed group were told about the categories of objects that would occur, and each time a picture was presented, its category label was given. The subjects in the incidental-informed group were not told to memorize the list but instead were given a task requiring them to make judgments of prototypicality about each of the objects. For the animal category, for example, if a horse was presented, subjects had to say how typical or representative of the animal class a horse is. We assumed that to make a judgment about the extent to which a horse is a prototypical animal necessarily activates the animal category.

Subjects in the intentional-uninformed group were told to memorize the list but were not given any category information. Subjects in the incidental-uninformed group were not told to memorize the list but were given a task requiring them to make judgments of prototypicality solely about the specific objects presented. For example, when shown a horse they were to judge how prototypical the portrayed horse was of horses in general. We assumed that to make a judgment about the representativeness of a particular horse in relation to other horses would not necessarily activate the superordinate animal category.

The recall data are shown in Figure 1. For the adults, recall and clustering were high whenever they were asked to memorize or when they were not asked to memorize but received the judgment task that activated the categorical organization. These data illustrate G. Mandler's principle that to organize is to memorize and to memorize is to organize (Mandler, 1967). When adults are told to memorize a list, they search for a way to organize the materials; if the list contains a number of obvious categories, typically they find and use this organization (although occasionally a serial or

FIG. 1 Number of words recalled when a categorical organization was either activated or not, under conditions of intentional and inciden...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- PREFACE

- 1. TYPES OF MENTAL STRUCTURE

- 2. STORY SCHEMAS AND PROCESSING

- 3. SCRIPTS AND SCENES

- REFERENCES

- AUTHOR INDEX

- SUBJECT INDEX