![]()

Chapter 1

SEA in International Perspective

The term ‘strategic environmental assessment’ (SEA) is now widely used to refer to a systematic process of analysing the environmental effects of policies, plans and programmes. Often, this process is equated with a formal procedure based on environmental impact assessment (EIA), as exemplified by the European SEA Directive (Directive 2001/42/EC), which came into force in July 2004 across the European Union (EU). However, for the purposes of this review, we consider the field of SEA to be much broader and to encompass a range of policy tools and strategic approaches as well as formal EIA-based procedures and near-equivalent forms of environmental appraisal. The boundaries of the field are mapped generically by reference to the function of SEA as a means of integrating environmental considerations into development policy-making and planning (which also are broadly considered).

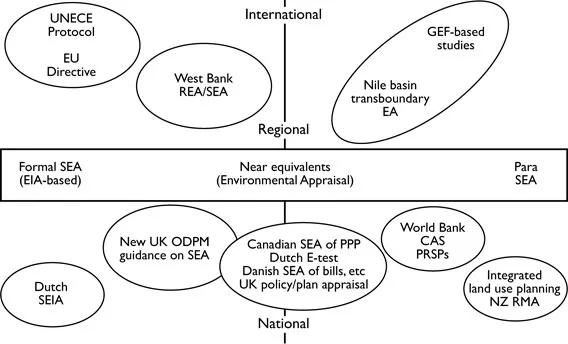

Within this frame of reference, different types of SEA can be recognized, although some are at an early stage of development (Figure 1.1). These include forms of ‘para-SEA’, a term we use for processes that do not meet formal definitions of SEA or their specification in law or policy but which have some of their characteristics and elements. At present, few developing countries have established formal arrangements for SEA of policies, plans or programmes, but a growing number apply SEA-type processes and elements of SEA. There is also increasing use of a family of para-SEA tools to ‘mainstream the environment’ in international lending and development. Here, a more strategic agenda is emerging, characterized by a greater focus on policy and programme delivery.

Notes:

Formal: prescribed in international or national EIA-type instruments

Near-equivalent: of environmental appraisal of policies/laws: and broader SEA-type processes/methods Para-SEA: don’t meet formal specifications or strict definitions; but share some characteristics or elements and have some overall purpose

Figure 1.1 Typology of SEA approaches

Depending on the jurisdiction or circumstances, SEA may also consider social and economic effects. Their inclusion as a matter of principle is widely supported in the literature on the field and, increasingly, SEA is seen as an entry point or stepping stone to integrated assessment or sustainability appraisal. A holistic, cross-sectoral approach to the implementation of sustainable development is promoted throughout the Plan of Implementation agreed at the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD), although what this approach entails is not spelled out. But there are numerous statements and recommendations on the development and use of policy tools and measures to strengthen development decision-making at all levels. These include explicit reference to EIA and integrated assessment and implicit reference to SEA, for example in the context of strengthening methodologies in support of policy and strategy (see Box 1.1).

Box 1.1 References to EIA and Integrated Assessment in the Wssd Plan of Implementation

EIA

Para 19 Encourage relevant authorities at all levels to take sustainable development considerations into account in decision-making, including on national and local development planning, investment in infrastructure, business development and public procurement. This would include actions at all levels to:

(e) Use environmental impact assessment procedures.

Para 36 Improve the scientific understanding and assessment of marine and coastal ecosystems as a fundamental basis for sound decision-making, through actions at all levels to:

(c) Build capacity in marine science, information and management, through, inter alia, promoting the use of environmental impact assessments and environmental evaluation and reporting techniques, for projects or activities that are potentially harmful to the coastal and marine environments and their living and non-living resources.

Para 62 Achieving sustainable development includes actions at all levels to:

(h) Provide financial and technical support to strengthen the capacity of African countries to undertake environmental legislative policy and institutional reform for sustainable development and to undertake environmental impact assessments and, as appropriate, to negotiate and implement multilateral environment agreements.

Para 135 Develop and promote the wider application of environmental impact assessments, inter alia, as a national instrument, as appropriate, to provide essential decision-support information on projects that could cause significant adverse effects to the environment.

Integrated Assessment

Para 15 [Re: accelerating the shift towards sustainable consumption and production … all countries should take action … at all levels to]:

(a) Identify specific activities, tools, policies, measures and monitoring and assessment mechanisms, including, where appropriate, life-cycle analysis and national indicators for measuring progress, bearing in mind that standards applied by some countries may be inappropriate and of unwarranted economic and social cost to other countries, in particular developing countries.

Para 40 [Re: implementation of an integrated approach to increasing food production … action should be taken] at all levels to:

(b) Develop and implement integrated land management and water-use plans that are based on sustainable use of renewable resources and on integrated assessments of socioeconomic and environmental potentials, and strengthen the capacity of governments, local authorities and communities to monitor and manage the quantity and quality of land and water resources.

Para 136 Promote and further develop methodologies at policy, strategy and project levels for sustainable development decision-making at the local and national levels, and where relevant at the regional level. In this regard, emphasize that the choice of the appropriate methodology to be used in countries should be adequate to their country-specific conditions and circumstances, should be on a voluntary basis and should conform to their development priority needs.

SEA is not referred to specifically in the WSSD Plan of Implementation, but it is implied, for example in Sub-section 136.

Source: Plan of Implementation, World Summit on Sustainable Development, final version, 24 March 2003 (www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/WSSD_POI_PD)

In this context, national sustainable development strategies (NSDS) are of particular interest. All countries are requested to prepare them by 2005 under the 2002 WSSD Plan of Implementation (www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/WSSD_POI_PD). They are in place already in some countries and in preparation in others. SEA and NSDS are related and mutually supportive instruments. First, the process of strategy preparation includes para-SEA elements such as evaluation of the state of the environment and identification of the critical trends and issues that require policy responses. Second, the NSDS provides a key framework for giving effect to SEA and more integrative approaches and particular attention is given to this relationship in this review (see OECD/DAC, 2001; and OECD/UNDP, 2002).

There is now considerable international interest in SEA with differing opinions and increasing debate about its nature and scope. Frequent conferences and workshops are held on the subject, and the literature on SEA is growing exponentially. An emerging theme of international debate concerns the applicability of SEA in developing countries, particularly with regard to the development and implementation of strategies for sustainable development and for poverty reduction. There is increasing demand for information and training on SEA. This outstrips supply despite the growing number and range of guidance materials and capacity-building programmes.

Many see this relationship simply as one of transferring the current approach to SEA from the North to the South. This occurs, for example, through the application of World Bank procedures and practices by borrowing and client countries and the design and delivery of training and capacity-building programmes. The revised edition of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) environmental impact assessment (EIA) training resource manual indicates that these programmes are still supply-motivated rather than needs-based (Sadler and McCabe, 2002). This calls into question whether SEA, as currently conceived and promoted, is necessarily an appropriate model for developing countries to adopt and adapt to their context and circumstances. There are arguments for and against this course of action. But, currently, this debate lacks a broader context and a larger range of alternatives that might be entertained.

This issue has become more pressing with the introduction of international legal frameworks for SEA, particularly the European SEA Directive (2001/42/EC) and the SEA Protocol to the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Convention on EIA in a Transboundary Context (agreed at Kiev in 2003). Both instruments prescribe an EIA-based procedure for SEA that draws heavily on the earlier European EIA Directive (1997/00/EC). Many observers expect the SEA Directive and the SEA Protocol to become international reference standards, certainly within the sphere of influence of the EU and its aid and assistance activities. The SEA Protocol is based on the Directive and will be open to signatory countries beyond the UNECE region. Over time, it may become a global instrument or a catalyst for other regions to establish their own multilateral framework.

Against this background, the rationale for undertaking a critical review and reappraisal of international experience with SEA comes into sharp focus. This review makes particular reference to the application of SEA in developing countries, where experience remains relatively limited and there are many challenges, and to countries in transition, where there is a richer vein of recent experience and much innovation in application. In this context, the concern is to gain a better understanding of the opportunities that SEA offers and the constraints on its implementation. We take a pragmatic approach and examine: the application of SEA tools and processes; how well they work in meeting their objectives – including protecting the environment; and what improvements can be made to assure sustainability and to integrate these considerations into economic development and poverty alleviation strategies. Earlier exercises along these lines have been undertaken in the Central and Eastern Europe region (Mikulic et al, 1998; Dusik et al, 2001), and for individual countries such as Samoa (Strachan, 1997).1

A more general stock-taking of international experience with SEA now seems appropriate, given the trends described in this chapter and in light of the apparent momentum to ‘transport’ SEA from the North to the South. There is growing enthusiasm on the part of many EIA practitioners in developing countries to adopt this approach. Yet their experience with conventional EIA is sobering. There is growing evidence that this process does not work well in many developing countries – see, for example, Mwalyosi and Hughes (1998) who review EIA experience in Tanzania. In most cases, the reasons are not so much technical, as issues of lack of political and institutional will, limited skills and capacity, bureaucratic resistance, antagonism from vested interests, corruption, compartmentalized or sectoral organizational structures and lack of clear environmental goals and objectives.

Undoubtedly, these structural problems will loom large as constraints to the introduction of SEA. In addition, there are many issues regarding the use of SEA in industrial countries that remain unresolved. These include continued opposition by national and international development agencies to the systematic application of SEA, particularly at the highest levels of policy- and law-making. A major issue in the negotiation of both the European SEA Directive (2001/42/EC) and the SEA Protocol to the UNECE Convention on EIA in a Transboundary Context (2003) was the scope of SEA application, particularly in relation to policy and legislation. These aspects are omitted from the Directive and included in the Protocol as non-binding. Yet this issue is far from settled and questions concerning the role of SEA in policy-making are likely to resurface once the Directive is implemented.

In the next chapter, we examine these challenges in relation to the emergence and evolution of SEA practice.

1 The results indicated that with respect to the information requirements, there is good potential for undertaking SEA in the short to medium term in Samoa. However, institutional capacities are limited and policy implementation effects are likely to influence the effectiveness of SEA.

![]()

Chapter 2

Surveying the Field of SEA

During the last decade, a number of reviews of strategic environmental assessment (SEA) experience have provided perspectives and background on this evolving field. Some of the key references and findings are described in this chapter. These are both incomplete and continually updated by papers on SEA in conference proceedings and journals. In the last five years in particular, the literature on SEA has expanded rapidly. But much of this simply represents the restatement and recycling of basic premises and themes on SEA. It is much less concerned with new insights or methodological advances. In many respects, SEA practice has run ahead of theory in applying the ideas and tools in a policy or planning context.

Not all of this is necessarily called or seen as SEA. Nevertheless, it forms part of a broad and expanding field. For example, during the last decade there has been considerable experimentation and innovation in development pla...