eBook - ePub

The Generative Study of Second Language Acquisition

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Generative Study of Second Language Acquisition

About this book

The vast majority of work in theoretical linguistics from a generative perspective is based on first language acquisition and performance. The vast majority of work on second language acquisition is carried out by scholars and educators working within approaches other than that of generative linguistics. In this volume, this gap is bridged as leading generative linguists apply their intellectual and disciplinary skills to issues in second language acquisition. The results will be of interest to all those who study second language acquisition, regardless of their theoretical perspective, and all generative linguists, regardless of the topics on which they work.

Information

Functional Categories

Chapter 1

Functional Categories and Related Mechanisms in Child Second Language Acquisition

Usha Lakshmanan

Southern Illinois University

Southern Illinois University

1. Introduction

Recent advances in linguistic theory within the framework of Principles and Parameters (Chomsky, 1981, 1986a, 1986b) have exerted considerable influence on the field of Second Language Acquisition (SLA). SLA researchers working within this framework of syntactic theory have investigated the extent to which developing second language (L2) grammars is constrained by principles of Universal Grammar (UG). An issue that received considerable attention during the 1980s concerned the role of UG parameters and parameter setting in SLA. The focus of most of this UG-based SLA research was on the adult L2 learner; the role of UG parameters in child SLA remained largely unexplored. More recently, however, this state of affairs has begun to change as SLA researchers are becoming increasingly interested in the role of UG in child SLA (for a detailed discussion of this issue, see Lakshmanan, 1995).

In addition to the role of UG parameters, another issue that has begun to receive increasing attention in SLA concerns the status of functional categories and nonthematic systems. Whereas much of the research that investigated the role of UG parameters in L2 acquisition was concerned with the adult L2 learner, research on the status of functional categories does not appear to be similarly biased, and child L2 acquisition has received equal attention with respect to this issue.

Current linguistic theory distinguishes between lexical and functional categories (Abney, 1987). Lexical categories include categories such as noun (N), verb (V), preposition (P), and adjective (A), which head the maximal projections of NP, VP, PP, and AP, respectively. Functional categories include I(nflection), C(omplementizer), and D(eterminer), which, like the lexical categories, are believed to head the independent maximal projections of IP, CP, and DP, respectively.

A question that is currently being debated by first language (LI) acquisition researchers is whether the full range of functional categories and their maximal projections are available in developing grammars from the very beginning or whether some functional categories are initially absent and only emerge at a later stage. According to one position (Guilfoyle & Noonan, 1992; Lebeaux, 1988; Radford, 1990), child LI acquirers go through an initial lexical-thematic stage where functional categories and nonthematic systems such as the Case system are absent. Radford (1990) specifically proposed that functional nonthematic systems mature or become operative roughly around the age of 24 months. This position is far from being uncontroversial, however, and many LI researchers, who espouse the continuity hypothesis, have argued that functional categories and related mechanisms are available from the very beginning (see, e.g., the studies by Deprez & Pierce, 1993; Hyams, 1992; Lust, 1994; Poeppel & Wexler, 1993; Valian, 1992).

Regardless of which position is the correct one, in the context of L2 acquisition, and successive child L2 acquisition in particular, we would expect that once functional categories and related mechanisms have become available for LI acquisition, they should at the same time be available for L2 acquisition as well. However, such an expectation differs considerably from the position held by some SLA researchers. Corder (1977, 1981) argued that L2 acquisition is a process of increasing complication. Initially, according to Corder, the L2 learner regresses to a basic language, which he claimed also characterizes the early stages of child LI acquisition. Although Corder did not provide specific details regarding the properties of such a basic language, he suggested that the grammar of this basic language is determined by semantics and situational context, rather than syntax. If Corder is correct, we would expect L2 learners to go through an initial stage where lexical-thematic systems are present but not functional-nonthematic ones.

Such a proposal has, in fact, recently been put forth in a study by Vainikka and Young-Scholten (1994), which examined the status of functional categories in adult L2 acquisition of German. Specifically, Vainikka and Young-Scholten claimed that only lexical projections are available at the earliest stages of L2 acquisition (for both adult and child L2) and that functional projections, which are input driven, emerge later with the I(nflectional) system emerging before the C(omplementizer) system (for arguments against this position, see Schwartz, 1993, and Epstein, Flynn, & Martohardjono, 1993).

In the context of child L2 acquisition, the emerging evidence regarding the status of functional projections seems to strongly suggest that functional categories and their projections are available from the very beginning stages of the L2. Lakshmanan (1993/1994) argued that in the case of children acquiring a second language in a successive L2 situation, functional categories and nonthematic properties such as Inflection and Case are operative from the very beginning. Child L2 learners do not appear to initially regress to a stage where only lexical-thematic properties are present. On the contrary, the evidence indicates that in the case of the child L2 learner, at whatever stage in LI acquisition functional categories and nonthematic systems become available, at the same time, they will be available for L2 acquisition as well. Lakshmanan and Selinker (1994) presented evidence for the availability of CP from the very beginning stages of child L2 grammars of English. Grondin (1992) and Grondin and White (1993) argued that DP, IP, and CP are available from the earliest stages in the child L2 grammars of French.

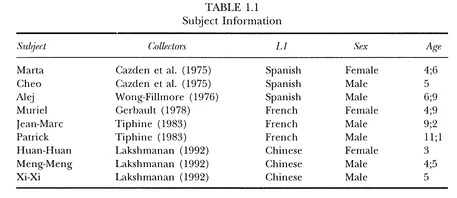

In this chapter, I present arguments supporting the position that Infl and the Case system are operative from the earliest stages of child L2 acquisition. In so doing, I examine evidence from the developing grammars of nine child L2 learners of English: three native speakers of Spanish (Marta, Cheo, and Alej), three native speakers of French (Muriel, Patrick, and Jean-Marc), and three native speakers of Chinese (Huang-Huang, Meng-Meng, and Xi-Xi). Information concerning these subjects is presented in Table 1.1.

2. INFL in Child L2 Grammars

As Lakshmanan (1993/1994) stated, one piece of evidence concerning the availability of the IP constituent in the early stages of child L2 development is the presence of the copula be. The copula be is overtly present even in the earliest stages of child L2 acquisition (often in the uncontracted form). This is illustrated by the utterances shown in (1) that were produced by Marta.

- (1) Mother is Mary Jo Fuster. (Sample 1)

- Is Hymie [ = That's Hymie.]

- My teacher is Christine. (Sample 1)

- This is Big Bird. (S2)

- This dress is here. (S2)

- Is black (S2)

Cancino (1977) examined the order of acquisition of morphemes in the L2 data for Marta and reported that the copula emerged very early—much earlier than has been reported for LI English-speaking children. The early emergence of the copula does not appear to be a peculiarity of Marta's L2 development alone and has also been observed for other child L2 learners (see, e.g., the studies by Dulay & Burt, 1974; Felix, 1976; Hakuta, 1975; Nicholas, 1981; Tiphine, 1983; and Wong-Fillmore, 1976).

INFL in adult finite clauses is positively specified for the features of tense and agreement. These features must be discharged onto a verbal element. Assuming that the copula in sentences such as those shown in (1) is underlyingly inside of VP, it must move to INFL to take on the features of tense and agreement. Because the copula in Marta's early L2 utterances is almost never omitted, it is possible that it functions as a place holder so that the contents (i.e., the affix features) of INFL can be discharged onto it.1

A second piece of evidence concerns the auxiliary be. In imitation tasks, even when the auxiliary be is contracted in the stimulus sentence, such instances of the be auxiliary are rendered uncontracted by Marta, as is illustrated by the utterances in (2).

(2) Native Speaker (NS): Mother's cooking supper.

M: Mother is cooking supper. (S2)

NS: Where's the baby sleeping?

M: Where is the baby sleeping? (S2)

If Marta had produced the is auxiliary only in its contracted form, for example, Mother's cooking supper, then we would not be certain that 's in expressions such as Mother's and where's has the status of an auxiliary in Marta's grammar. However, the fact that the is auxiliary is rendered uncontracted by Marta suggests that it is functioning as an auxiliary verb in Marta's grammar, and that it is in INFL position. As in the case of the copula, the auxiliary is appears to function as a place holder for the contents of INFL.

Let us now turn to supporting evidence from the English L2 grammars of two Chinese-speaking children, Huan-Huan and Meng-Meng. As can be seen from the examples in (3a), which were produced in the context of a picture description task, the auxiliary is was often omitted from contexts where it would be required in English.2

- (3a) This little baby sleeping in the big bed. (Meng-Meng, S3)

- He walking (Huan-Huan, SI)

However, it is interesting that in the very same samples where utterances such as those in (3a) occur, there were also instances where both children produced the auxiliary was even though the contexts in question required the use of the present tense form. This can be seen from the examples in (3b).

- (3b) He was /grai/ [ = He is crying, (in the context)] (Huan-Huan, SI)

- This little girl was watching the movie. [ = This little girl is watching a movie, (in the context)] (Meng-Meng, S3)

The data in (3a), when considered along with the data in (3b), suggest that in utterances of the type in (3a), the auxiliary is probably present, although in its null form, and that the failure on the part of these children to overtly supply the auxiliary is may be a phonological problem and may be related to the fact that in the spoken input it typically appears in the contracted form (except when it occurs in sentence-final position). However, unlike the auxiliary is, the auxiliary was is not similarly contracted and is therefore more salient to the learner. As in the case of Marta, these two Chinese-speaking children seem to know that the Infl features of tense and agreement must be discharged onto a verbal element. Although in several cases, Infl is present in the null form, in a few instances the xuas auxiliary is selected to function as a place holder for the features of Infl, even though it does not exactly match the target form required in the context.

A third piece of evidence for the early emergence of INFL concerns negation and inversion in questions. In the negative constructions that appear during the early stages of child L2 grammars of English, the negative element always occurs after is (copula/auxiliar...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Functional Categories

- Part II Constraints on Wh-Movement

- Part III Binding and Related Issues

- Part IV Phonology

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Generative Study of Second Language Acquisition by Suzanne Flynn,Gita Martohardjono,Wayne O'Neil in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Desarrollo personal & Historia y teoría en psicología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.