![]()

CHAPTER

1

Introduction

Purposes of This Text

Why Do We Make Measurements in the Assessment and Management of Childhood Language Disorders?

What Problems Accompany Measurement?

A Model of Clinical Decision Making

PURPOSES OF THIS TEXT

The distraught parents of a 3-year-old with delayed communication arrive at the office of a speech-language pathologist, youngster in tow and anxiety emanating almost palpably with every word: “Does our child have a serious problem?” “What can be done to correct it?” “How effective will treatment be?”

Although the children and the specific questions change, the scene remains the same: A child’s parents or teacher turn to a speech-language clinician for help that will include answers to specific questions about whether a language problem exists, its nature, and how to intervene to minimize or remove its effects. This book focuses on basic elements of measurement of childhood language disorders as the means of providing valid clinical answers to these questions because only with valid clinical answers can effective clinical action be taken.

Specifically, this book is designed to prepare readers to select, create, and use behavioral measures as they assess, manage, and evaluate treatment efficacy for children with language disorders. Although it is designed to provide guidance for those working with children with any language disorder, the greatest attention is paid to specific language impairment, autism, and language disorders related to mental retardation and hearing impairment.

This book is intended primarily for graduate and undergraduate students who expect to enter the field of communication disorders. It may also serve as a refresher for professionals, such as practicing speech-language pathologists or teachers, who have never been formally introduced to some of the basic concepts behind the wide range of measures used in the assessment of childhood language disorders or who would like an introduction to the latest developments in this area.

Unfortunately, the topic of measurement in childhood language disorders has the reputation of threatening complexity. Indeed, measurement of language, or communication more generally, is complex both because of the wealth of abilities and behaviors underlying language use and because of the variety of measurement orientations on which speech-language pathology and audiology draw. Although direct roots in educational and psychological testing traditions are particularly robust, there are also connections to measurement traditions in linguistics, personnel management, medicine, public health, and even acoustics. The approach taken here attempts to blend the best of these traditions and alert readers to the elements they share.

For all readers, the text is intended to achieve three goals. First, readers will learn to recognize the bond that ties the quality of clinical actions to the quality of measurement used in the process of clinical decision making for children with suspected language disorders. Second, they will learn how to frame clinical questions in measurement terms by considering the information needed and the specific methods avail able to answer them. Third, they will learn to recognize that all measurement opportunities present alternatives—at times alternatives of comparable merit, but more often alternatives that vary in their ability to answer the clinical question at hand. This last goal will enable readers to act as critical consumers and discriminating developers of clinical tools for language measurement. Case examples are used frequently in the text to help readers apply new concepts and methods to specific problems like those they currently face or will soon encounter.

WHY DO WE MAKE MEASUREMENTS IN THE ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF CHILDHOOD LANGUAGE DISORDERS?

The following three cases illustrate a variety of occasions in which measurement serves as the basis for clinical actions involving children with various language difficulties.

Two-year-old Cameron has been scheduled for a communication evaluation because of parental concerns that he uses only two words and does not appear to understand as well as his older sister did at a much younger age. Additionally, he generally avoids eye contact, which his parents find particularly alarming because of recent exposure to a television show on autism. Thus, they have specific questions about whether their child has autism and what they can do to improve his ability to communicate with other members of the family.

Alejandro, a diminutive 9-year-old who hardly seems imposing enough for such a distinguished name, moved from Mexico to the United States a year ago, has just moved into a new school district. Although he has been diagnosed with a language disorder, no information concerning the relation of that language disorder to his bilingualism has accompanied him to his new school. Decisions regarding his school placement and access to special services will hinge on that information.

Four-year-old Mary Beth has been referred by her pediatrician to your private practice for a complete evaluation of her communication skills. Although she has been receiving speech-language treatment since she was 2 years of age because of Down syndrome, Mary Beth has not made progress at the rate expected by her regular speech-language pathologist or desired by her parents. In fact, she appears to have made almost no progress in the past year and may be losing skills in some areas.

These three cases illustrate the varied problems facing children and families who turn to speech-language pathologists for solutions. They also illustrate the speech-language pathologist’s role as part of a larger team of professionals.

First, Cameron’s parents are faced with a child who appears quite delayed in his expressive and receptive language and who may also evidence difficulties in the nonverbal underpinnings of communication. Addressing their chief concern will require an interdisciplinary effort involving several professionals (including possibly a psychologist, a neurologist, a developmental pediatrician, and a social worker) designed to yield a differential diagnosis. If autism is diagnosed, the need for interdisciplinary efforts will continue because of the array of problems often associated with autism—ranging from mental retardation to sleep disorders. The family’s needs, as well as the child’s, may be intense, with the result that the speech pathologist’s focus on the child’s communication may broaden to encompass the family communication context as well as the coordination of efforts aimed at the child’s overall needs.

Alejandro presents the speech-language pathologist with the difficult task of determining to what extent his language difficulties are differences not unlike those facing anyone with undeveloped skills in a new language versus to what extent they reflect an underlying disorder in language learning affecting both his native and second languages. In addition to decisions regarding the nature of direct therapy that he should receive (including whether it should be conducted in Spanish or English), critical decisions regarding his classroom placements are pressing. Not only will the speech-language pathologist need to work closely with his family and teachers to reach these decisions, he or she may also need to work with a translator or cultural informant to arrive at the best decisions for Alejandro’s academic and social future.

Finally, Mary Beth’s parents and pediatrician are interested in receiving information that will shed some light on her lack of progress in speech-language treatment. Such information could help guide her subsequent treatment by providing her parents, pediatrician, and regular speech-language pathologist with a better understanding of her current strengths and weaknesses and, consequently, a better understanding of reasonable next steps. It should be noted, however, that Mary Beth’s parents might also use this information as they consider suing the speech-language pathologist responsible for her care. Although this prospect is remote, it is nonetheless an increasing possibility (Rowland, 1988).

These three cases reveal that speech-language pathologists are asked to obtain and use information to help children from a variety of cultural backgrounds and a range of communication problems. Although they obtain much of that information directly, they must often work with families and other professionals to stand a chance of getting the “facts.” Speech-language pathologists use some of this information themselves, such as when they identify and describe a language disorder or plan their role in treatment. They also share information with others, including doctors, teachers, and other individuals who work with persons experiencing a communication disorder. In brief, then, speech-language pathologists generate, use, and share information having potentially vital medical, educational, social, and even legal significance.

So how does measurement enter into the strategies used to address children’s needs? Put simply and in terms specific to its use in communication disorders, measurement can be seen as the methods used to describe and understand characteristics of persons and their communication as part of clinical decision making, the process by which the clinician devises a plan for clinical action. Thus, it is the connection between clinical decisions and clinical action that makes measurement matter (Mes-sick, 1989). Clinicians make numerous, almost countless decisions about a child in the course of a clinical relationship—from determining that a communication disorder exists, to selecting a general course of treatment, to examining the efficacy of a very specific treatment task. Because the clinician bases her actions at least in part on measurement data obtained from the client, the quality of the action will be closely related to the quality of the data used to plan it. The section that follows considers several decision points that offer opportunities for successes—or failures—in clinical decision making.

WHAT PROBLEMS ACCOMPANY MEASUREMENT?

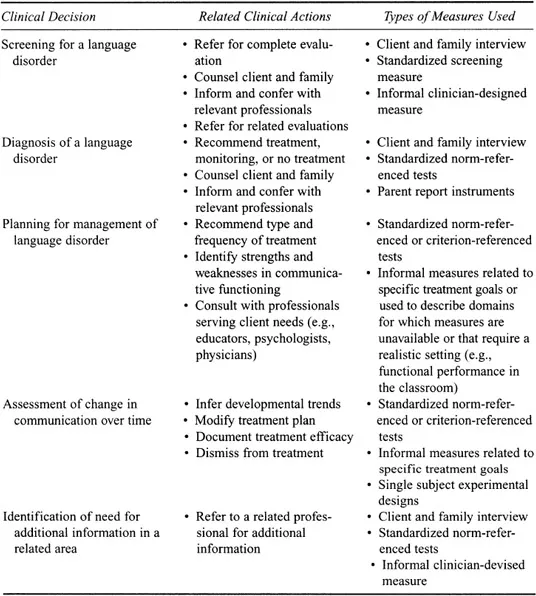

Table 1.1 lists five different kinds of decisions occurring in the course of a clinical relationship as well as some of the measures that might be used to provide input to each decision. This listing is intended to illustrate the variety of decisions to be made rather than to list them exhaustively. As illustrated in the table, decision making begins even prior to the initiation of an ongoing clinical relationship, as the speech-language pathologist screens communication skills to determine whether additional attention is warranted. Subsequently, the clinician will require more information to understand the nature of the problem presented and to arrive at decisions about how best to manage it. Once a program of management is in place, ongoing measurement is required to respond to the client’s changing needs and accomplishments. Even the end of the clinical relationship is based on the clinician’s use of measurement with dismissal from treatment usually occurring when communication skills are normalized, maximum gains have been effected, or treatment has been found to be unsuccessful. At each of the points of decision making, the potential for harm enters hand in hand with the potential for benefit.

A brief reconsideration of the case of Mary Beth can be used to illustrate the potential for clinical harm as well as to introduce a method for evaluating the effects of different kinds of errors in decision making. Recall that Mary Beth has received speech-language treatment for 2 years because of an early diagnosis of Down syndrome. Her lack of any progress in speech and language over the past year, or worse yet, her loss of skills, may represent a poor fit between the assessment tools used to measure progress and the areas in which Mary Beth has in fact advanced, or it may represent some unsatisfactory clinical practice of her regular speech-language pathologist. On the other hand, this lack of progress may reflect a change in Mary Beth’s neurological status that requires medical attention. Therefore, one of the most immediate decisions to be made from a speech-language perspective is whether to refer Mary Beth to a neurologist.

TABLE 1.1

Clinical Decisions in Speech-Language Pathology

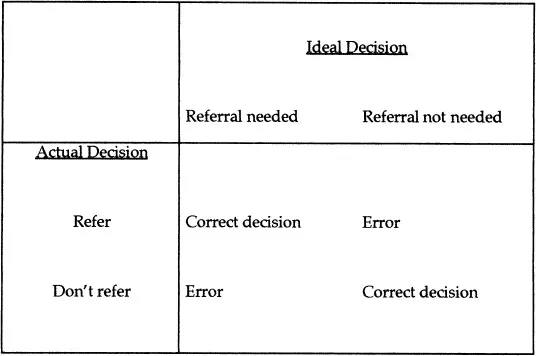

Figure 1.1, a decision matrix, illustrates a method for thinking about the possible outcomes associated with this particular decision. This type of decision matrix has been used to assess the implications of alternative choices in a variety of fields (Berk, 1984; Thorner & Remein, 1962; Turner & Nielsen, 1984). To construct such a matrix as a means of considering repercussions for a single case, one pretends that one has access to the ultimate “truth” about what is best for Mary Beth. From that perspective, a referral either should or should not be made—no doubts.

FIG. 1.1. A decision matrix for the decision of whether to refer Mary Beth for neurologic evaluation.

With such perfect knowledge, therefore, suppose that a referral should be made. In that case, the clinician will have made a correct judgment if he or she has referred and an incorrect one if he or she has not. If the clinician errs by not referring, Mary Beth may become involved in the expense and frustration of continuing speech-language treatment that is doomed to failure. Further she may be delayed in or prevented from receiving attention for an incipient neurologic condition, which, in turn, could ...