Everywhere, Naturally?

We yearn for the divine. On a planet of 6.9 billion people, a full 6 billion of us practice some form of religion. Christians, Muslims, and Hindus make up two-thirds of the total; the remaining 1.4 billion practice Buddhism, Shinto, Sikhism, Judaism, the Bahá’í Faith, and various folk religions. In all, 87 percent of humans profess a belief in some supernatural deity. This is a compelling number.

Is this ocean of faith in something invisible and intangible a throwback to some more primal longing? No, not if a relatively upscale lifestyle is any gauge. Consider this: In the United States, a country that ranks among the highest in the world with regard to technological advancement, a nation with a standard of living envied by much (if not all) of the world, nearly its entire population—9 out 10 people—believes in God; 84 percent say that they engage in “conversational prayer” in which they talk with God in their own words.1 In a Gallup poll, 59 percent state that religion plays an “important role” in their life.2

Primal or not, believing in some supernatural deity apparently is at least a very old practice. In The World’s Religions, Houston Smith says that for the bulk of human history, religions were present, but oriented around the tribe. When we look at cave art, carvings, and the remains of prehistoric humans accompanied by various burial objects, it is easy to see that our early ancestors might have believed in some kind of deity and afterlife.

But artifacts, symbols, and iconography are really all that we have; we do not know what our ancient ancestors thought about religion. In today’s world, direct sensory experiences with God or the divine are not widely published; those who claim literal encounters often show other signs of mental illness. And although the Bible and other holy books tell stories of individuals, such as Moses, who are said to have directly communicated with God, such accounts yield a range of metaphorical and literal interpretations. It is probably safe to say that the vast majority of people who believe in God do not have Moses-like experiences. Yet we remain faithful.

It might sound like a far-fetched comparison, but think about this: most of us have never had a firsthand experience of Antarctica, yet we completely trust that it is there because we have hard evidence of its existence. In a world driven by the realities of what we can confirm with our five senses, why we continue to have faith in some unseen God is a puzzle. In The Descent of Man, Darwin suggests a belief in supernatural beings that have power over the cosmos is universal. In his book Timeless Healing, Herbert Benson of the Harvard Medical School’s Mind/Body Institute says there has never been a civilization that did not believe in a God, Gods, or some supernatural force.

Perhaps these things are true. But a type of faith that defies the five senses, is universally believed, and spans cultures, geographies, and time suggests something worthy of our consideration: believing may not be entirely learned— some of it, somehow, might be hard-wired naturally into our brains.

Even if such faith were innate, the world’s religions are still a diverse mix of beliefs and practices. But they also have underlying similarities, especially regarding creation and belief in a powerful, omnipresent deity. Admittedly, we often seem to focus on why a certain religious affiliation is different or not on the right path; sad to say, we even dehumanize and oppress others on the basis of their beliefs. But despite diversity, our physiology and the role the brain plays in our heavenly yearnings and convictions are all, humanly, very much the same.

Something else that we do also is humanly the same: we talk. The famous linguist Noam Chomsky says our ability to use human language is innate, and although words of similar meaning from different cultures and countries often sound different, certain fundamental principles of communication are shared by people the world over.

Several years ago, Ken received a call from a person who was writing an article for one of the Christian magazines. Apparently the caller wanted a neurologist somehow to support the notion that God made humans speak in different languages. A discussion ensued about the Tower of Babel and how, after the Great Flood, all people spoke a common language. It seems that Nimrod, Babylon’s king, along with his people, decided to build a tower that was so tall it would reach into heaven. Not pleased with such arrogance, the God of the Old Testament punished humanity by confounding the common language: he made diverse groups of people use different words for the same concepts. Of course, the result was that the groups could not understand each other. But we now know that is not the end of the story—there is more to talking than just the meaning of words.

More than words, often how we say something most effectively conveys our intentions. Language communicates not only ideas (what we call propositional speech), but also emotions and feelings through alterations in pitch, loudness, and timing. Similarly, facial expressions can announce our sentiments. In an important study in 1969, the psychologists Paul Ekman and Wallace V. Friesen demonstrated that people isolated from other cultures could still understand apparently universal, emotional facial expressions. Expressions conveying anger, sadness, happiness, surprise, disgust, and fear without words are understood across societies. Ken told this writer that whereas humanity may have been punished for building the Tower of Babel, God did not alter this universal and fundamental means of communicating.

So if emotional expressions are transcultural, there is a high probability that they are not entirely learned, but rather, in part, are hard wired in the brain and is genetically transmitted from parent to child. We are suggesting the same for the human belief in God.

Although people all over the world use propositional speech and emotional communication, one could argue that many people do not believe in God or are agnostic; therefore, the capacity for such belief is not universal. But that is a premature conclusion. Some people decide to live their lives in silence, and many portray little emotion through their speech. This abstention from speech or near absence of emotion in speech does not mean that these capacities are not innate. We might even see strident atheists and agnostics knocking on wood or crossing their fingers.

The God Spot: Searching for the Seat of the Soul

For the most part, the anatomy and physiology of the brain determine how it functions. And both of those are governed primarily by genetics. Because a majority of people in almost all cultures believe in a God or Gods, and have done so throughout recorded history, it seems likely that such a faith is similarly genetically determined: the sophisticated network of neural interconnections that regulate what and how we believe is, at least partially, passed from parent to child.

We do not know exactly where in the brain such a religious-belief network would be located or how it might work. It is not clear how such a “God spot” induces faith in the supernatural or motivates the religious behaviors that can accompany believing. Moreover, we do not really understand why these networks might have formed in the first place. Admittedly, there is a lot we have not yet grasped.

Hippocrates and other ancient physicians were aware that injury and disease in different parts of the brain could cause varying behavioral symptoms. So we have known for centuries that particular regions of the brain have specific functions. But the source of our belief in the supernatural has remained a mystery. In the seventeenth century, René Descartes was one of the first to look for what he considered the “seat of soul.”

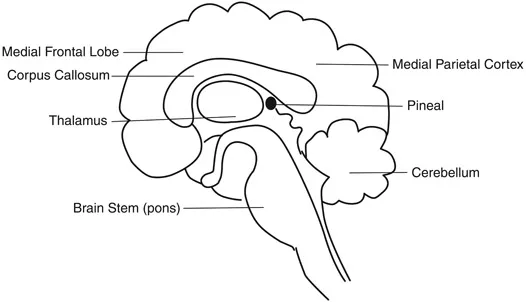

Definitions of the soul abound. For some religions, it embodies our spiritual nature, that part of us that continues to exist after death. Descartes believed that the soul was the container for all of the information pouring into our brains, that all thought and action arose from it. Working from a fundamental understanding of anatomy, he surmised that the soul was located at the center of the brain in a structure called the pineal (Figure 1.1). Although Descartes thought the pineal was the seat of the soul, scientists have discovered that this gland produces melatonin, important in sleeping and waking patterns.

Descartes, of course, did not have the benefit of modern imaging technologies such as computer tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). But neither did Ken when he was a medical intern at Bellevue Hospital in the early 1960s (although x-rays were being used). Descartes, then, might have appreciated a certain story from Ken’s training days.

Figure 1.1 The pineal gland. If the brain is divided into two equal halves from front to back, such that the left hemisphere is separated from the right, this would be a midsagittal section. In this section the pineal gland, in the middle of the brain, can be seen. If the pineal was calcified and an x-ray of a normal person’s skull was taken, the pineal would appear here, in the middle. But if the person had a tumor or blood clot, the pineal would be pushed away from its central position.

A middle-aged, comatose man had just arrived at the emergency room. The resident and Ken, the intern on call, were quite concerned that this fellow might have some kind of mass, such as a blood clot or tumor, dangerously pushing on his brain. They used an ophthalmoscope to look inside his eyes, expecting to see a bulging optic nerve as evidence of such a mass. But there was no such indication with this patient; they would have to try something else. Injecting a special dye into an artery leading to the brain could facilitate observation, but that would take time—too much time. In addition, serious complications, such as stroke, can result from this procedure.

The resident asked Ken to take the patient to x-ray to shoot some cranial images. This was to see if the pineal gland had been moved out of it midline position by any impinging mass. But the resident also gave Ken some specific instructions, which Ken found interesting: “Tell the x-ray technician that if this fellow’s x-rays do not show a calcified pineal, then image him again, but rotate his head during the procedure.” Ken recalls that while hurriedly pushing the patient on a gurney, he asked the resident why they needed to do this. The resident explained: “If the pineal, which is in the middle of the head, is calcified, you can see it on the x-ray. However, if it is not calcified, we won’t see it unless we rotate his head. In other words, everything in the x-ray will be blurred because you are moving it—except for the relatively still, center point of rotation.” Pretty clever, but four hundred years ago, this would not have been news to Descartes: he, too, knew the pineal was located in the center of the head.

Recall that in addition to knowing the pineal gland’s location, Descartes also believed that the soul and our thoughts, ideas, and actions emanated from this spot. But around that same period, an early pioneer in anatomical brain research, the British physician Thomas Willis (1621–1675), was thinking something else.

Willis, the founder of the British Royal Society, was one of the first people to use the term neurology. He was also at the forefront of exploring the functional changes associated with diseases of the brain and identified a number of the essential blood vessels. Even today, in a testament to his competence, we refer to the vasculature at the base of the brain as the Circle of Willis. In his estimation, having a clear understanding of the brain was key to penetrating the soul; studying it could “unlock the secret places of Man’s Mind and [give us a] look into the living and breathing Chapel of the Deity.”

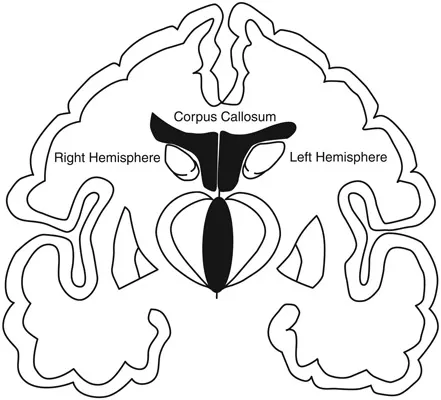

Unlike Descartes, Willis thought that God had placed the soul in the corpus callosum—the central structure that joins, and enables communication between, the left and right hemispheres of the brain (see Figure 1.2). Today, we know that the corpus callosum performs a very critical function, but why Willis thought the soul was located here is a bit of a puzzle.

Long after Willis’s death, studies conducted in the early twentieth century suggested that when the corpus callosum is injured, we will often see evidence of something called a hemispheric disconnection syndrome. In such a disconnection, each side of the brain acts independent of the other, giving rise to certain peculiar behaviors. Perhaps Willis observed something like this with one or more of his patients.

Apart from injury, the corpus callosum is sometimes intentionally severed. Some patients have severe epileptic seizures that cannot be controlled with medication. One means of stopping the spread of such attacks from one side of the brain to the other is to separate the hemispheres surgically. In this type of surgery, the entire corpus callosum is severed. Without doubt, it is a serious procedure, and afterward the ability of one hemisphere to communicate with the other is severely limited. Several years ago Ken had the opportunity to examine Ellen, a woman who had undergone such a procedure for seizure control. When he asked Ellen if she had any problems now, post-surgery, she told him, “Sometimes my two hands get into arguments.”

Figure 1.2 The corpus callosum. This drawing of the brain is a coronal section. If a knife is used to cut the brain downward from side to side (e.g., right to left), the result is a coronal section. This section reveals the corpus callosum, the major cable connecting the right and left hemispheres.

Ellen explained. Several days earlier, she had been wearing a red dress; when she reached into the closet with her right hand for her matching red shoes, her left hand suddenly pulled the shoes from her right hand, put them back on the rack, and selected blue shoes. Because she wanted the red shoes to go with her dress, her right hand took the blue shoes from her left—and again selected the red shoes. But as she was picking them up her left hand slammed the closet door on her right hand...