![]()

The locations of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTIONS

THE very notion of The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World raises questions for both of its nouns and both of their adjectives. Why seven? What was so wonderful about these particular wonders? What do we mean by the Ancient World – ancient for whom and what sort of world?

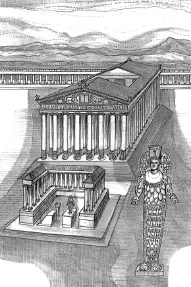

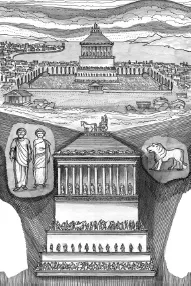

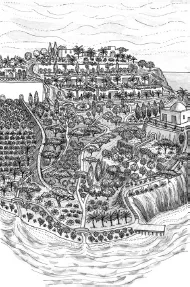

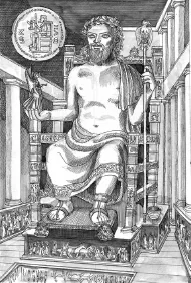

Interestingly, the notion did not start with Wonders but with Sights. The two words in Greek were quite similar and the one slipped into the other naturally enough: theamata turned into thaumata. These Seven Sights – for the armchair travellers of the Hellenistic and Roman worlds to sight-see as they read about them – had to be, in the nature of things, wonderful enough to arouse awe in the first place. On the whole, it was scale of engineering and/or luxury of concept and appointment that prompted the choice. The Pyramids of Egypt had both – unparalleled scale and a seemingly over-luxuriant expenditure of effort to construct them. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon were self-evidently a luxurious indulgence achieved by triumphs of engineering (which were equally apparent in the great walls of that city). The gigantic Statue of Zeus at Olympia was decked in the most elaborate adornment and sculpted by the most ingenious means. The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus combined scale with vivacity of decoration and pioneering architectural devices. The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus was the biggest tomb in the Graeco-Roman world (after the Pyramids) and exhibited an ostentatious compendium of international styles put together with massive engineering effort. The Colossus of Rhodes, even in the wrecked state into which it fell within half a century of its completion, continued to proclaim the majesty of its conception and ambition of its construction as a ruin. The Pharos lighthouse of Alexandria was before all else an essay in innovatory engineering on a grand scale.

Greatness of size, luxury of appointment and boldness of concept and execution, combining to make a vivid imaginative impact on those who saw them and those who read about them: these were the qualities that first got these sights-cum-wonders listed, in a certain cultural context that we call the Hellenistic world. The same qualities went on recommending them to the Roman world that succeeded and absorbed the Hellenistic one. (With the end of the Roman empire, there came also the end of the entire epoch that we know as ‘the Ancient World’, reaching back beyond Hellenism through classical Greek and biblical times to the older civilisations of Egypt and Mesopotamia whose first rise marked the beginnings of ‘ancient history’ for the Western world.)

Hellenism was the international culture that Alexander’s conquests of the late fourth century BCE engendered in Greece, in the (mostly eastern) Mediterranean world of Greek colonies and in the Greek-ruled reaches of Egypt and Asia Minor (and some way beyond). Hellenism spoke Greek and read Greek and was heir to the religious, artistic and intellectual traditions of the classical Greeks; but it encompassed, too, the rougher ways of the Macedonian Greeks from whom Alexander the Great himself had sprung and the frankly oriental habits of the peoples brought into the fold in the east. (Alexander, for one, liked to dress up as a Persian and to put on the semi-divine pretensions of the eastern monarchies.) Hellenism survived the political break-up of Alexander’s empire at the hands of his succeeding generals and thrived in the cities they maintained, to greatly influence the Roman empire in due course.

Of course, Hellenism did not come into being overnight with Alexander of Macedon. Many of the seeds of its flowering were germinating in late classical Greece. With its trading depots in Egypt and its important commercial cities along the coast of Anatolia, Greece had long been on the receiving end of exotic influences; in some of its richer colonies, in the western Mediterranean too, Greek culture had already taken a turn for the luxurious and even megalomaniac before the coming of the Macedonians in the late fourth century BCE. (BCE = Before the Common Era; CE = the Common Era of our present dating system.)

The philosopher Plato who died in 347 BCE, a decade after Alexander was born, could evidently see the Hellenistic way of life coming in his own day. His moral tale of Atlantis, one of the last things he wrote, was designed to contrast the old, sober virtues of the Greeks (as he saw them) with a changing world’s new and luxurious vices, which he projected backwards in time onto his Atlanteans. These Atlanteans finally took grandeur, including self-aggrandisement, luxurious excess and high-handed ambition so far that, for all their power, they were defeated – thousands of years ago in Plato’s fiction – by the virtuous Athenians of yore, and then drowned by the gods. Plato might have welcomed the Macedonians at first as a stern, firm hand on the degenerating Greeks around him: he would have been appalled to find Alexander going on to usher in a semi-oriental empire of greedy commerce, ostentation, showy mixed-up religions and everybody on the make. It is to be very much doubted whether he would have been at all impressed with the Seven Wonders of the World that Hellenistic culture was to make so much of.

One of the bonuses of Hellenism was the growth of a sort of university ethos that saw, in the institutions of museums and libraries, the coming-together of scholars to survey and catalogue the achievements of their forerunners in the Greek world and among the non-Greek communities now under Greek influence. Books, above all, were collected, copied, studied, quoted and plagiarised: and it was in the great modern city that Alexander founded on the Delta coast of Egypt that all this went on most famously. Alexandria was the intellectual hub of the Hellenistic ancient world and it was very likely where the Seven Wonders of that world were first listed in the second century BCE.

But all seven (or more) of them were known about before ever they were brought together on any list of the second century BCE. The Zeus statue was on the Greek mainland itself (and the most westerly of the sights). The temple at Ephesus, the Mausoleum and the Colossus of Rhodes were more or less on a line down the south-west coast of Anatolia, long inhabited by Greeks. If you extended that line south across the Mediterranean you reached the Greek city of Alexandria itself where the Pharos beamed its light to incoming ships. Further south in Egypt there were the unmissable pyramids by Memphis, well-known to the Greeks for hundreds of years. Furthest away to the east from the Mediterranean world was Babylon on the Euphrates, where Alexander had died in 323 BCE, long familiar to the Greeks in the works of the historian and travel writer Herodotus. It wasn’t knowledge of these various sights that was new in the second century BCE: it was just that the idea of singling them out for their grandeur and magnificence and writing them up on a list was a typically Hellenistic venture. (Herodotus had already written of the ‘three greatest works’ of the Greeks, all of them – a tunnel, a jetty and a temple – on the island of Samos, as it happened: the naming of wonders was in the air even in the fifth century BCE.)

The world of Hellenism was, of course, but a small part in reality of the diverse doings of human beings on our Earth in the last centuries before the Common Era. Outside the Mediterranean region and its immediate hinterlands – except down into Egypt and towards the east where Alexander’s army had reached as far as the Indus and there were established trade routes to modern-day Afghanistan – little was known of the wider world. A few travellers brought back tales of remoter parts, often more or less incredible, with a seepage of similarly unreliable anecdotes from trader to trader across vast lines of exchange that might throw some sort of light on, say, north-west Europe or Africa beyond Egypt or the plains of Asia or distant China. But worthwhile knowledge of these areas was largely unavailable, and completely so as far as vast tracts like the Americas and Australasia were concerned, whose very existence was unknown to the Hellenistic world. What sights and wonders might the compilers of the wonder lists have considered for inclusion if they had known more about the whole wide world of which they formed a small part? They would, no doubt, have applied their fashionable tests for scale and ambition to any far-flung wonders that came their way – and in due course we shall look at the available candidates, on a contemporary global basis, to rival each of the standard seven wonders in turn.

It has been said that in Hellenism we see the first light of our own modern world, with its large-scale political organisation, its vigorous commerce with money in coinage and an international language written in an easily learned alphabet, its town planning, its confidence in technology (up to a point), its cosmopolitan culture, its multi-ethnic urbanisation, its religious relativism, its professionalism and institutionalising of scholarship. All this is often persuasive, but it pays to remember that the past is indeed always a foreign country and they do things differently there. Religion, science, engineering, scholarship were all conducted on the basis of quite different assumptions from those we take for granted now, in a world of often very different social relations, of which the existence of slavery is the most glaring example. The Greeks themselves had to recognise this inevitable difference of the past when they looked back to the scarcely believable creation of such wonders as the Pyramids of Egypt or the Hanging Gardens of Babylon and we must remember how different a world it was from our own that created the great cult statue of Zeus at Olympia or the temple at Ephesus with its grotesquely many-breasted goddess or the overblown tomb of Mausolus or the colossal statue of the sun-god at Rhodes. Only the Pharos, the last wonder to join the list, looks altogether like something we might have wanted to create in our modern Western world. Let’s hope future generations will look back on our own works with an understanding eye.

We know that in the library of Alexandria at around 270 BCE the scholar-poet Callimachus of Cyrene wrote a book called Curiosities from All over the World which reflected, perhaps established, the idea of cataloguing wonderful things, but this work has not survived and evidently did not restrict itself to seven most wonderful of wonders. The first records we have of the practice of listing seven sights and wonders as such belong to the second century BCE. The so-called Laterculi Alexandrini and the collection of poetic fragments known as the Palatine Anthology both include reference to such lists. In the latter, the epigrammatist Antipater of Sidon (mainly a composer of funeral verses who spent his last years in Rome, dying a drunk there according to one account) is credited with a list very close to the one with which we are all now familiar. It differs only in making two entries for Babylon – the city walls as well as the gardens – and leaving out the Pharos. Something of its poetry comes through even in translation. ‘I’ve looked on the walls of impregnable Babylon, which chariots may race along, and on Zeus beside the river Alpheus. I’ve seen the Hanging Gardens and the Colossus Sun-God, the great man-made mountains of the tall Pyramids, and the gigantic tomb of Mausolus. But when I saw the sacred home of Artemis that reaches up to the clouds, the others were put in the shade for the Sun has never seen its equal outside of Heaven.’ It is interesting that the one wonder that on paper seems the least exciting to us (we all know what Greek temples were like, don’t we?) should have aroused the greatest admiration at the launch of the Seven Wonders of the World.

The idea of a list of seven wonders probably took hold quite quickly after the time of Antipater, though its precise items may very well have been a bit changeable from the start. But we don’t know for sure that this listing by seven was popularly established until the last days of the Roman republic, in the time of Julius Caesar. Diodorus Siculus, who wrote an anthology of world history in the second half of the first century BCE, records that an obelisk of the legendary Babylonian queen Semiramis ought to be on any list of seven great works. In a piece attributed, probably wrongly, to the Roman librarian Hyginus, of about the same time, the Palace of Cyrus at Ecbatana (further east than Babylon) ousts the Hanging Gardens of Antipater. And Strabo only a few years later, who wrote on historical and geographical themes, mentions the idea of seven sights, among them the pyramids. He does describe among other remarkable things the statue of Zeus at Olympia in the course of his geographical/historical tour d’horizon, but not specifically as one of any canon of seven. The list’s existence is hinted at by the Latin poet Propertius at about the same time: he would like to think his poetry will prove more endurable than the Pyramids, the Zeus temple and the Mausoleum. In the first century of the Common Era, the ‘natural historian’ Pliny and the poet Martial similarly attest to some practice of wonder-listing, though with novelties like the Labyrinth of Thebes in Egypt (actually the ruins of the great temple complexes there), the Colosseum in Rome and the Altar of Horns on the island of Delos among their sights worth seeing. Also featuring at various times in various authors’ works were the Asclepium (temple-cum-hospital) of Pergamum, and the Capitol of Rome.

It may be that Antipater’s original list (without the Pharos and with two sights for Babylon) went on as the most popular listing: a work that poses as a product of the Alexandrian engineer Philo (who lived at about the same time as Antipater) repeats his catalogue precisely, but apparently at a much later date. The real Philo (‘of Byzantium’, as we know him in full) wrote a Mechanical Handbook, which survives in part to reveal itself as mostly concerned with siege engines and defensive devices. The bogus Philo seems to have listed his seven sights in the fourth century CE, but the first report of his list comes in a ninth century manuscript. On the grounds, chiefly, of this Philo’s florid and theologically imaginative style in discussing his seven sights, classical scholars dissociate him from the sober, practical engineer of Alexandria in the second century BCE. Of course, the fourth century impersonator of Philo may simply have been giving himself historical credibility by reproducing old Antipater’s list.

The Pharos, although discussed by earlier writers like Pliny, only made it onto the lists with Gregory of Tours (536–594 CE), who like other Christian authors shied away from some of the old pagan entries like the Zeus and Artemis monuments – they at least had the merit of having existed – in favour of things like Noah’s Ark and the Temple of Solomon, of which the same cannot be said. This difference of approach to the drawing up of wonder lists tells us a lot about the intellectual divergence of the Christian from the Ancient World. The situation with the various listings also reminds us that our modern canon of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World is as much the product of recent convention as of some fixed listing in the ancient world itself. True, Antipater more than two thousand years ago advertised a list very close to our own, but the Pharos wasn’t on it (and, as we shall see, the Hanging Gardens perhaps shouldn’t have been). Our Seven Wonders of the World are really an imaginative composite of ancient wonders, fixed now by long usage since the Renaissance revival of interest in the classical world.

Why were seven wonders listed from at least the second century BCE? For the same reason, essentially, as there are seven days of the week. And, mythologically, Seven Days of Creation, Seven Heavens, Seven Against Thebes, Seven Japanese Gods of Luck, or Seven Wise Men of Greece, Seven Virtues, Seven Chinese Sages of the Bamboo Grove, Seven Deadly Sins, etc. etc. For the same reason, too (though it all looks more everyday), that there are Seven Hills – and churches – of Rome, Seven Senses, Seven Ages of Man, Seven Seas, Seven Planets, even Seven Dials in Holborn and Seven Sisters along the South Downs. Human beings have come to love the number seven – perhaps it even has some neurological appeal. At all events, the Babylonians of the first millennium BCE esteemed this number highly and passed their enthusiasm on to the compilers of the Hebrew Bible; and to Greek thinkers like Pythagoras of the late sixth century BCE, whose followers made much of this number in their influential mathematico-mystic system. Seven was seen as a perfect number of anything to have. And so, Seven Wonders, Seven Sights; even if they were not always the same seven as have come through to us.

Two of the seven wonders were actual products of the Hellenistic world: the Colossus of Rhodes, which may have been idealisticall...