![]()

I

FAMILIES AND SCHOOLS: HOW CAN THEY WORK TOGETHER TO PROMOTE CHILDREN’S SCHOOL SUCCESS?

![]()

1

Family Involvement in Children’s and Adolescents’ Schooling

Jacquelynne S. Eccles

University of Michigan

Rena D. Harold

Michigan State University

We have known for some time that parents play a critical role in both their children’s academic achievement and their children’s socioemotional development (e.g., Clark, 1983; Comer, 1980, 1988; Eccles, Arbreton, et al., 1993; Eccles-Parsons, Adler, & Kaczala, 1982; Epstein, 1983, 1984; Marjoribanks, 1979). It is only recently, however, that researchers have studied the role schools play in encouraging and facilitating parents’ roles in children’s academic achievement. Critical to this role is the relationship that develops between parents and teachers and between communities and schools. Although a relatively new research area, there is increasing evidence that the quality of these links influences children’s and adolescents’ school success (e.g., Comer, 1980; Comer & Haynes, 1991; Epstein, 1982, 1987; 1990; Stevenson & Baker, 1987; Zigler, 1979), in part because high quality linkages make it easier for parents and teachers to work together in facilitating children’s intellectual development (e.g., Bronfenbrenner, 1974, 1979; Epstein, 1983, 1986; Epstein & Dauber, 1988; Jacobs, 1983; Stevenson & Baker, 1987). Yet, mounting evidence suggests that parents and teachers are not as involved with each other as they would like to be. Several studies find that parents want to be more involved with their children’s education and would like more information and help from the schools in order to meet this goal (Baker & Stevenson, 1986; Comer, 1980, 1988; Dauber & Epstein, 1989; Dornbusch & Ritter, 1988; Leitch & Tangri, 1988; Rich, 1985). Teachers also want more contact with parents (Carnegie Foundation, 1988; Epstein & Becker, 1982). Furthermore, the situation gets worse as children move from elementary school into secondary school, when parents’ active involvement at the school declines dramatically (Carnegie Corporation, 1989; Epstein, 1986).

The message, then, seems clear: Both teachers and parents think collaborative involvement in children’s education is important. So why are parents and teachers not more involved with each other? This question usually takes the form of “why aren’t parents more involved at school?” and we discuss a variety of reasons why this is true (e.g., time, energy andlor economic resources; familiarity with the curriculum and confidence in one’s ability to help; attitudes regarding the appropriate role for parents to play at various ages; and prior experiences with the schools that have left some parents disaffected). But, even more importantly, the extent of family–school collaboration is affected by various school and teacher practices, characteristics related to reporting practices, attitudes regarding the families of the children in the school, and both interest in and understanding of how to effectively involve parents. There is mounting evidence that specific school and teacher practices are a major factor influencing parent involvement (Dauber & Epstein, 1989; Epstein, 1986; Epstein & Dauber, 1991). Furthermore, the power of schools and teachers to influence parent involvement and to improve parent-school links has been demonstrated even with hard-to-reach parents (e.g., Comer, 1980, 1988; Epstein, 1990). According to Epstein (1990): “Status variables are not the most important measures for understanding parent involvement. At all grade levels, the evidence suggests that school policies and teacher practices and family practices are more important than race, parent education, family size, marital status, and even grade level in determining whether parents continue to be part of their children’s education” (p. 109). So why aren’t parents more involved at school? Why is it so difficult for schools and families to work together more effectively in educating children?

To fully understand what is limiting parent involvement, a general model of parent involvement is needed. Presenting such a model is a primary goal of this chapter. Another goal is to summarize the results of two studies designed to investigate this model. The first study—The Michigan Childhood and Beyond Study (MCABS)—focuses on the elementary school years. The second study—The Maryland Adolescent Growth in Context Study (MAGICS)—focuses on the junior high school years. For each of these studies we present findings regarding the amount and type of parent involvement in their children’s intellectual education. When possible, we compare these findings with parents’ more general levels of involvement in other aspects of their children’s lives, particularly in the development of their children’s athletic abilities. We then summarize preliminary analyses of the predictors of parent involvement outlined in Fig. 1.1. In these summaries, we focus on the proximal influences on parent involvement both at home and school. Finally, we make recommendations regarding better strategies for more effective collaboration between schools and parents in the service of children’s education.

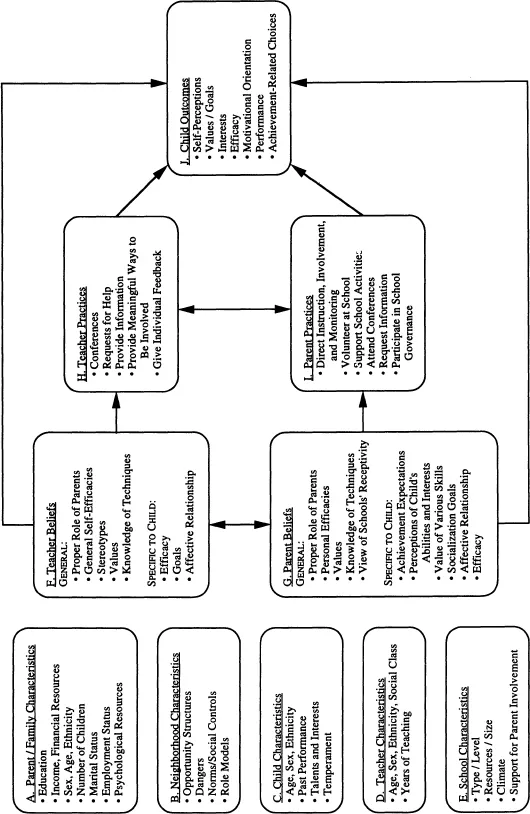

FIG. 1.1. A model of the influences on and consequences of parent involvement in the schools.

INFLUENCES ON PARENT INVOLVEMENT

As noted previously, a theoretical framework or model is needed to guide an analysis of effective parent involvement. One such model is presented in Fig. 1.1. This model provides a framework for thinking about the dynamic processes that underlie parents’ involvement in their children’s education (Eccles & Harold, 1993). It treats parent involvement as both an outcome of parent, teacher, and child influences, and as a predictor of child outcomes. It also suggests a framework for thinking more generally about the ways in which both schools and parents influence children’s school performance.

In Fig. 1.1, we hypothesize that there are a variety of influences on parent involvement. The first set of influences (commonly referred to as exogenous variables—variables that have indirect or more global and removed effects on parent involvement) are summarized in the left column of Fig. 1.1. They include various family/parent characteristics, neighborhood/community influences, child characteristics, general teacher characteristics, and school-structural and general-climate characteristics. We have included no arrows connecting these five boxes with the others in the model because these variables have both direct and indirect effects on all of the other boxes. The second column (boxes F and G) includes teacher and parent beliefs and attitudes. This model assumes these beliefs and attitudes affect each other and have a direct effect on the two boxes in the third column, namely, specific teacher practices (box H) and specific parent practices (box I). Finally, the variables listed in boxes F, G, H, and I are assumed to affect directly the child outcomes listed in the last column (box J). This model summarizes a wide range of possible relations among the many listed influences. For example, the impact of the exogenous variables listed in boxes A, B, C, D, and E on teachers’ practices of involving parents (box H) are proposed to be mediated by teachers’ beliefs systems (box F) including their stereotypes about various parents’ ability and willingness to help their children in different academic subjects. Some of the child outcome variables listed in box I are identical (or very similar) to the child characteristics in box C. This overlap is intentional and captures the cyclical nature of the relations outlined in the model. Today’s child outcomes become tomorrow’s child characteristics; so the cycle continues over time. A more detailed discussion of the most important of these many influences follows.

Parent/Family Characteristics

Numerous studies document the relation between parent involvement and such characteristics as family income, parents’ education level, ethnic background, marital status, parents’ age and sex, number of children, and parents’ working status (e.g., Baker & Stevenson, 1986; Bradley, Caldwell, & Elardo, 1977; Bradley, Caldwell, & Rock, 1988; Clark, 1983; Coleman & Hoffer, 1987; Coleman et al., 1966; Corno, 1980; Eccles-Parsons, 1983; Epstein, 1990; Harold-Goldsmith, Radin, & Eccles, 1988; Marjoribanks, 1979). For example, better educated parents are more involved both in school and at home than other parents; parents with fewer children are more involved at home; but family size does not affect the amount of involvement at the school; and employed parents are less likely to be involved at school but are equally involved at home (Dauber & Epstein, 1989). The following parent/family characteristics are also likely to be important:

1. Social and psychological resources available to the parent (e.g., social networks, social demands on one’s time, parents’ general mental and physical health, neighborhood resources, and parents’ general coping strategies).

2. Parents’ efficacy beliefs (e.g., parents’ confidence that they can help their child with schoolwork, parents’ view of how their competence to help their children with schoolwork changes as the children enter higher school grades and encounter more specialized subject areas, and parents’ confidence that they can have an impact on the school by participating in school governance).

3. Parents’ perceptions of their child (e.g., parents’ confidence in their child’s academic abilities, parents’ perceptions of the child’s receptivity to help from their parents, parents’ educational and occupation expectations and aspirations for the child, and parents’ view of the options actually available for their child in the present and the future).

4. Parents’ assumptions about both their role in their children’s education and the role of educational achievement for their child (e.g., what role the parents would like to play in their children’s education, how they think this role should change as the children get older, how important they believe participation in school governance is, and what they believe are the benefits to their children of doing well in school and having parents who are highly involved at their children’s school).

5. Parents’ attitude toward the school (e.g., what role they believe the school wants them to play, how receptive they think the school is to their involvement both at home and at school, the extent to which they think the school is sympathetic to their child and to their situation, their previous history of negative and positive experiences at school, their belief that teachers only call them in to give them bad news about their child or to blame them for problems their children are having at school versus a belief that the teachers and other school personnel want to work with them to help their child).

6. Parents’ ethnic, religious, and/or cultural identities (e.g., the extent to which ethnicity, religious, and/or cultural heritage are critical aspects of the parents’ identity and socialization goals, the relationship between the parents’ conceptualization of their ethnic, religious, and/or cultural identities and their attitudes toward parent involvement and school achievement, and the extent to which they think the school supports them in helping their children learn about their ethnic, religious, andlor cultural heritage).

7. Parents’ general socialization practices (e.g., how does the parent usually handle discipline and issues of control versus autonomy, and how does the parent usually manage the experiences of their children).

8. Parents’ history of involvement in their children’s education (e.g., parents begin accumulating experiences with the school as soon as their children begin their formal education. Parents have also had their own experiences with schools as they as grow up. These experiences undoubtedly affect parents’ attitudes toward and interest in involvement with their children’s schools and teachers).

Community Characteristics

Evidence also suggests that neighborhood characteristics such as cohesion, social disorganization, social networking, resources and opportunities, and the presence of undesirable and dangerous opportunities affect family involvement (e.g., Coleman et al., 1966; Eccles, McCarthy, et al., 1993; Furstenberg, 1993; Laosa, 1984; Marjoribanks, 1979). These factors are associated with variations in both parents’ beliefs and practices, and opportunity structures in the child’s environment. For example, Eccles, Furstenberg, Cook, Elder, and Sameroff are studying the relation of family management strategies to neighborhood characteristics as part of their involvement with the MacArthur Network on Successful Adolescent Development of Youth in High-Risk Settings. These investigators are especially interested in how families try to provide both good experiences and protection for their children when they live in high-risk neighborhoods—neighborhoods with few resources and many potential risks and hazards. To study this issue, they are conducting two survey interview studies (one of approximately 500 families living in high- to moderate-risk neighborhoods in inner-city Philadelphia and the other of approximately 1,400 families living in a wide range of neighborhoods in a large county in Maryland). Initial results suggest that families who are actively involved with their children’s development and in their children’s schooling use different strategies depending on the resources available in their neighborhoods. Families living in high-risk, low-resource neighborhoods rely more on in-home management strategies to both help their children develop talents and skills and to protect their children from the dangers in the neighborhood; families in these neighborhoods also focus more attention on protecting their children from danger than on helping their children develop specific talents. In contrast, families in less risky neighborhoods focus more on helping their children develop specific talents and are more likely to use neighborhood resources, such as organized youth programs, to accomplish this goal. Equally interesting, there are families in all types of neighborhoods who are highly involved in their children’s education and schooling (e.g., Eccles, McCarthy, et al., 1993; Furstenberg, 1993).

Such neighborhood characteristics have been shown to influence the extent to which parents can successfully translate their general beliefs, goals, and values into effective specific practices and perceptions. Evidence from several studies suggests that it is harder to do a good job of parenting if one lives in a high-risk neighborhood or if one is financially stressed (e.g., Elder, 1974; Elder & Caspi, 1989; Flanagan, 1990a, 1990b; Furstenberg, 1993; McLoyd, 1990). Not only do such parents have limited resources available to implement whatever strategies they think might be effective, they also have to cope with more external stressors than White middle-class families living in stable, resource-rich neighborhoods. Being confronted with these stressors may lead parents to adopt a less effective parenting style because they do not have the energy or the time to use a more demanding but more effective strategy. For example, several investigators find that economic stress in the family (e.g., loss of one’s job or major financial change) has a negative affect on the quality of parenting (e.g., Elder, 1974; Elder, Conger, Foster, & Ardelt, 1992; Flanagan, 1990a; Harold-Goldsmith et al., 1...