![]()

Part I

Ecological Architectures within a Broader Context

![]()

Intensification

Nature is becoming part of history in the sense that we are making irreversible impacts on the very processes that sustain its course. This is a dramatic shift from nature playing the role of reliable constant backup, the home to which boys could return after their games. This irreversibility impacts not only nature, but also our sense of ourselves and our powers.1

Environmental activist Dave Foreman speaks to the superhuman nature of our globally transformative collective activity: “As the cause of today's mass extinction, we humans are no longer just a biological phenomenon but now are a physical factor equivalent to an asteroid or continental drift in radically changing biological diversity.”2

In the blinding light of an asteroid, the casting of nature as a neutral, dependable backdrop to human affairs gives way to a more complex characterization. Nature is both subject to blind rage and the subject of silent vulnerability. In such a complex psychological realm, patterns of urban growth and development are the shape of environmental futures, the fate of an enormous number of plant and animal species, and the prospect for ecosystems to continue to function and provide critical services.

While demand for dramatically responsive environmental architectures challenges a profession beset with responsibility, it also opens new and exciting possibilities of design performance, expression, and impact. There are myriad dimensions to the environmental predicament that demand the architect's attention and, due to their collective gravity and simultaneity, call into question deeply held assumptions about the profession, about nature, and about the function of the city. It warrants considering some of these and what might constitute a suitably comprehensive architectural response.

An ecological approach to architecture requires minimization of energy consumption and the generation of as much of it on site as possible. This entails optimizing building performance by relating program (a list of activities to consider and spaces to plan for) to climate and site conditions (orientation and degree of sunlight available, for instance), and maximizing opportunities to passively heat, cool, and ventilate interior spaces. Where possible, it involves overlapping occupancy schedules so spaces efficiently serve multiple uses. When desirable, it means solving local problems locally and segregating spaces differing in function and energy load. As an example, Behnisch and Partners separated laboratories from offices as a formative move in their competition-winning design entry for the IBN Institute for Forestry and Nature Research (Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1993–1997); this organization makes it possible to satisfy strict mechanical ventilation standards for labs while maximizing passive conditioning of offices.

In an environmentally conscious design approach, dynamic, often highly nuanced, and sometimes invisible qualities inform spatial organization. Harrison Fraker contends:

A complete understanding of the relevance of passive concepts on architectural form goes beyond the formal analysis of visual qualities alone. It requires perception … of thermal and luminous phenomenon that are not visible in the same sense as architectural space. Boundaries in the thermal or luminous environment are subtle and not sharply defined.3

Other factors extend the boundaries of responsibility of an architectural proposition: the energy expended and carbon offset during construction, the flexibility and adaptive capacity of building assemblies relative to changing circumstances, and the potential of materials and systems to serve useful roles when a building's life has passed. This undertaking represents a disintegrated/integrated approach, where incompatible elements are designed to retain autonomy while others are more tightly embedded in assemblies. The degree of integration of components depends on their temporal synchronicity, the likely frequency of change based on wear, obsolescence, etc. To adopt a notion from McDonough and Braungart, designers are called upon to develop means of “upcycling” architectural “nutrients”; that is, assigning to building materials future roles commensurate with their full potential so as to minimize environmental impacts such the amount of construction debris entering landfills.4

These efforts are considered “ecological” in that they render more explicit building behavior, decrease dependence on far-flung energy systems, fossil fuel-based economies, and overflowing waste facilities, and in other ways reduce environmental footprint. While perhaps not “net zero impact,” these projects would nevertheless help close the loop by contributing to the decentralization of highly inefficient systems of resource distribution. While these material and energy efficient approaches to project development may or may not result in improved biophysical processes on a site and its immediate surroundings, they indirectly enhance broader scale ecological function by not taxing the power grid and other infrastructures that impact regional air, water, and habitat quality.

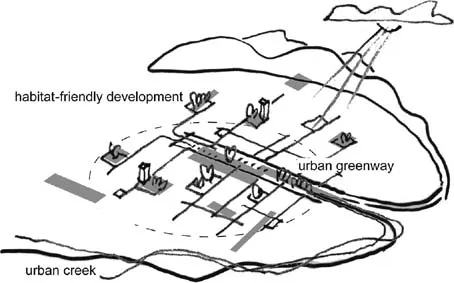

With a goal of attenuating processes of habitat degradation and species extinction, architects and their collaborators are called upon to create resourceful forms of development that address functioning of natural systems, in large measure through consideration of how the biological and physical attributes of a site and newly constructed interventions on it connect to adjacent sites and broader-scale terrestrial, aquatic, and avian ecological networks. An ecological approach to development discourages conceptualizing an individual project as autonomous and capable of providing for all the needs of its inhabitants (human and nonhuman), however resourceful it may be, and looks to synergy accruing from proximity to a diversity of valuable services nearby. One key lesson of landscape ecology is the value of linking scales; for example, how design interventions can engage in processes of site repair in conjunction with more encompassing efforts toward green urban redevelopment and regeneration.

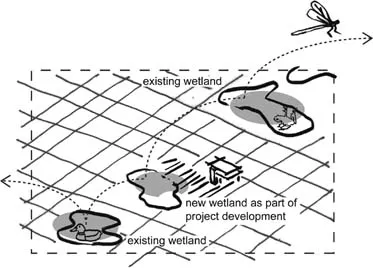

The ecological role of a site-scale development may pertain to facilitating connectivity for terrestrial species through maintenance or establishment of green corridors linking to neighboring properties and open spaces. It may function as a stopover for birds during their continental-scale migration. A project's ecological contribution may also pertain to ways it acts as a functional component of a watershed, where it collects and treats water from the site and perhaps those adjoining so as to improve overall hydrological function and ensure watershed and aquatic habitat quality (issues until recently considered beyond the purview of architectural responsibility).

Site-scale green developments connect to and support neighborhood and region-scale (urban) ecological networks.

Political ecologists point out that overly narrow construal of problems and singling out of certain factors as most significant can lead inadvertently to making other environmental problems worse. In order to gain a more comprehensive awareness, in order to address the range of factors described above as inherent to a deeper form of sustainability, designers benefit by partaking in the discourse that influences how environmental problems are constructed and conceptualized, as opposed to adopting this discourse uncritically. Environmental philosopher Bryan Norton argues:

One simply cannot overemphasize the key role of problem formulation in seeking cooperation and success in environmental management. And at the heart of problem formulation is the question of how we talk about – how we articulate and discuss – environmental problems.5

A project as a stepping-stone supporting species movement in an urban landscape.

An ecoarchitecture as a form of “critical” political ecology relies on the ability of a project team “to reveal the hidden politics within supposedly neutral statements about ecological causality.”6 The conceptualization of a work of architecture is at once the gathering of the best available information, the space of dialog, and an accounting of responsibility. A realized work of architecture testifies to the process and breadth of environmental consideration; it is the outcome of the non-neutral set of approvals, contracts, simulations, and representations that optimally pertain to resource efficiency as well as to how a project functions as an alteration of dynamic (eco)systems over time.

Organizers of conferences, symposia, and summits dedicated to advancing green strategies for designing built environments frequently portray climate change as the environmental problem, one that, due to its severity, trumps all other issues.7 While climate change is the monster in the bestiary, a monumental threat demanding immediate and aggressive response on the part of architects and society at large, other environmental issues deserve the designer's attention. “Simultaneous stressors” include diminished air and water quality and a downward spiral of habitat fragmentation and consequent loss of biodiversity. Ecosystem degradation and simplification account for the mass extinction now underway, the sixth in the history of the world and the first precipitated by a species. The political scientist Stephen Meyer offers a sobering description of the momentum of this event: “The average rate of extinction over the past hundred million years has hovered at several species per year. Today the extinction rate surpasses 3,000 species per year and is accelerating rapid...