![]() II

II

Family Narratives![]()

3

A Hmong Family

Refugees from Laos

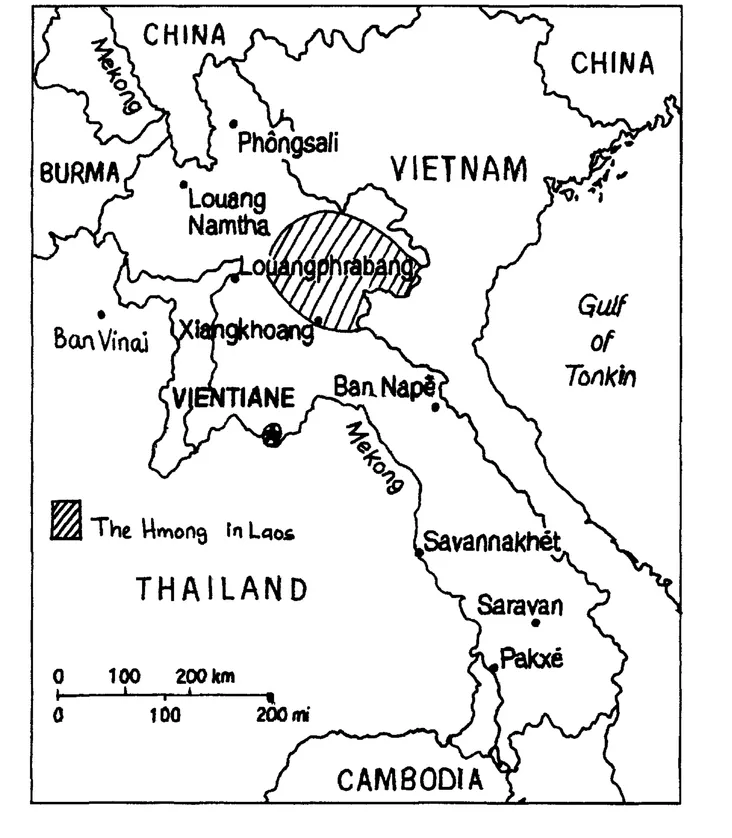

The history of the Hmong people can be traced back at least 5,000 years. Over time, the Hmong have wandered, or been driven, southward through China, from the fertile river valleys to the harsher environment of the high mountains. Centuries of struggle with the Chinese empire climaxed in the so-called "Miao" Rebellion in Guizhou Province from the 1850s to the 1870s. The rebellion ended with a province destroyed, millions reported dead, and the Hmong people serving as scapegoats for the wider peasant revolt against high taxes and the injustices of the central government. To preserve their lives and their freedom, many Hmong moved southward, into Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, and Burma (Jencks, 1994). In a brief overview to the Hmong's long history of struggle and relocation, Trueba and Zou (1994) asked: "What would make us think that the (Hmong)—after centuries of migration—have retained an ethnic identity, a sense of peoplehood?" (p. 3).

In 1959, the CIA, concerned about the growing communist insurgencies in Southeast Asia, began seeking the support of the Hmong of Laos.1 The Hmong under the leadership of General Vang Pao agreed to provide military support and to help build air bases for the Americans near their villages. By the early 1960s the Americans and the Russians were heavily arming the opposing factions within Laos, and war engulfed the Hmong people in the

north. As is usual in war, the first casualty was the truth: Most Americans were not told of the U.S. involvement in Laos until 1970. What the Hmong were told was that the American's would come to their aid should the war go badly. The Hmong under the leadership of Vang Pao agreed to fight with the Americans against communists in Southeast Asia. A decade and more of the "secret war" in Laos left thousands of Hmong dead and dozens of villages destroyed, especially in Xieng Khouang Province on the border with Vietnam (Hamilton-Merritt, 1993).

In 1973, the Paris Peace Accords signaled the end of American military involvement in Southeast Asia; in Laos, a peace agreement was signed between the warring factions. Two years later, the Pathet Lao communists pressured the Laotian king to send Vang Pao out of the country. As the Vietnam War came to an end, the North Vietnamese Army and Pathet Lao closed in on Hmong strongholds in the north of Laos. Vang Pao and several of his supporters were airlifted out of the airbase at Long Chieng, but thousands of Hmong men, women and children were left behind to fend for themselves, no longer with American support. Many died in a war of attrition carried out by the new Lao People's Democratic Republic and their Vietnamese allies (Hamilton-Merritt, 1993). Moreover, much of the high mountain agricultural system had been destroyed in the war, and the Hmong faced an economically bleak future (Cooper, 1986).

With the proclamation of the Lao People's Democratic Republic in 1975, many changes came to the Hmong villages. Old village leaders were replaced with new. Small private farms were consolidated and collectivized. Traditional gender, family, and communal relationships were challenged. Free public education was extended to the remotest mountain villages. "Seminars" were arranged for those who were unable or unwilling to adapt to the new changes, and many never returned from their stays in the reeducation camps (Hamilton-Merritt, 1993). A vast exodus occurred as Vang Pao's soldiers and their families, Hmong clan leaders, and all those who were either unwilling or unable to live under communist rule left Laos for Thailand. The road was often treacherous, and encounters with communist troops could prove disastrous. The crossing of the Mekong is the theme of countless Hmong pandau, or story cloths, which depict vivid scenes of this part of Hmong history.

By the late 1970s, the eastern Thai border was home to 21 refugee camps set up to receive hundreds of thousands of people fleeing Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. These camps were supported by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and staffed by volunteers, among whom were many missionaries. However, the Thai government was influential in determining official and unofficial refugee camp policies. Camps were opened and closed by Thai authorities, and refugees were shifted about. In general, the Thais favored repatriation of refugees, even though many feared for their lives if they were returned to their homelands. "These periodic shifts from camp to camp effectively terrorized the refugees, because they could never be certain when they would be uprooted again or, worse yet, sent across the border" (Long, 1993, p. 49; see also The Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, 1989).

Tens of thousands of Hmong were living in camps in Thailand by 1980, principally in Chiang Kham, Ban Nam Yao, and the large camp at Ban Vinai. Ban Vinai, the largest Hmong settlement in the world at that time, contained over 40,000 people in an area of less than 1 square mile (Long, 1993). The reeducation of refugees destined for America began in these camps in Thailand. Tollefson (1989) suggested that refugees were presented with an unrealistic portrait of life in the United States, while at the same time, they were made to feel the unworthiness of their own cultures:

The counterfeit universe presented to refugees in the educational program at the processing centers is planned and purposeful. The unrealistic vision of life in the United States, the myths of American success ideology, the denigration of Southeast Asian cultures, and the effort to change refugees' behavior, attitudes, and values result from systematic decisions by policymakers throughout the educational bureaucracy, (p. 87)

Camp life was squalid, crowded, and dangerous for refugees who feared reprisals from Lao communists, Thai communists, and Thai government soldiers. Despite the difficulties of the camps, however, many Hmong refugees did not want to "board the bus" for America (Ranard, 1989). The lessons of American success they learned in the reeducation programs were more than counterbalanced when they received letters from relatives in America, and read their tales of isolation, poverty, and fear in strange cities.

The first Hmong refugees arrived in Fox Valley, Wisconsin, in 1975, and today they make up the largest minority group in the area. In the following pages, Faye Van Damme, a preschool ESL teacher who works mostly with Hmong children, presents her dialogic teacher research with the Lor family. Assisted by her bilingual paraprofessional, Khou Lor, Ms. Van Damme focuses on the life of Chan Lor, orphaned at an early age in Laos, and now adjusting to life in the United States.

FIG. 3.1. Khou arid Chan Lor at the United Nations Building, New York City, March 1999.

FIG. 3.2. Khou and Chan Lor with Faye Van Damme, New York City, March 1999.

THE LORS

Faye A. Van Damme With Chan and Khou Lor

January 15, 1983. The misty air hung heavy around the jungle covered mountains; hills of shelter and protection, as well as doom and death. This is a place with a war-ravaged countryside, where the inhabitants are homeless and hungry, where innocent farmers are prisoners, where one, young, 13-year old is without a father and mother, where darkness is all around.

January 15, 1983. The subzero temperatures grip the air sending chilly shivers down spines. The small town is encased in the white of midwinter snows. This is a place with a sense of comfort and security, where homeowners raise families and prosper, where streetlights illuminate the roadways leading to supermarkets and schools, where citizens live freely, where one, young, 17-year-old is surrounded by family and friends, where darkness is all around.

The darkness is broken by bursts of light: one by gunfire and land mines; the other by birthday candles and flashbulbs. In the days prior to this date, preparations have been made for each of the events occurring half a globe apart. Secret meetings were held in the safety of the trees, messages were carried on the lips of the couriers, escorts and boats were arranged, money was spent. Guest lists were written and invitations mailed, messages sealed in colorful envelopes, decorations and games were arranged, money was spent.

As the day approaches arid the events unfold, emotions are intensified by anticipation. For the Hmong boy of Laos, there is tension, eagerness, nervousness, danger, and urgency, as he prepares to leave his mother behind in the hilltops to cross the mighty Mekong with his uncle's family. For the Anglo girl of Wisconsin, there is excitement, eagerness, lightness, gaiety, and high spirits as she awaits the arrival of guests.

There is much laughter and frivolity as friends and family enter the balloonand streamer-filled house. Games are played, gifts are opened, and cake is eaten, all in the name of fun.

There is no laughter, only seriousness and dead quiet. It is a 15-mile walk to the shores of safety. It is unknown who is going to die. Many lose their feet from walking on land mines. Shirttails are held, boats are loaded, and strangers are trusted, all in the name of freedom.

January 15, 1983. On this day two people, separated by land and sea, experience two totally contrasting events. On this day one experiences a celebration of birth, while one experiences a celebration of rebirth.

How is it possible that two people from unlike cultures with extremely different pasts should happen to meet in Oshkosh, Wisconsin? Currently, I am teaching preschool English as a Second Language (ESL). Because the class is composed of Hmong students, I have a bilingual assistant who is Hmong. Over the course of the school year, we have established a relationship that reaches beyond a professional one; we have built a friendship. When I first learned of this family narrative study, I immediately thought of telling the story of my assistant, Khou. After explaining the project to her, she responded, "My story isn't very interesting, you should talk to my husband, Chan." And so it was decided that I would tell the story of Chan Lor. The following pages hold the history, thoughts, and feelings of Chan as he grew up in Laos, fled, relocated to the United States, and was "educated" in American schools and society. I have a special interest in the role school played in Chan's life, as well as his thoughts and viewpoints of the responsibilities schools have to immigrants.

Chan Lor's Story

Not so long ago, a boy child was born. I am that first born child. My name is Chan Lor, and I was born in the small, mountain village of Xieng Khouang, Laos, in 1970. At that time, my dad was a CIA agent who had joined the Hmong army at age 11. When I was 1 year old, my family and I moved to the large modern city of Long Cheng. The airport was busy and cars filled the streets. This is where the American CIA headquarters were located. Even before the CIA arrived, Long Cheng was a city, compared to most of Laos, where agrarian villages dotted the lush mountainsides.

Due to the war with the communists, we moved a lot as I was growing up. in 1973, my dad died. No one is quite sure what happened to him. He was just missing. Since he was a soldier fighting against the communists, it is most likely he was killed. My mom and I went to live with my mom's parents when I was 5 years old. We made the journey from Long Cheng to my grandparents' mountain village by foot, as was the customary mode of travel.

Here we stayed for about 1 year. When the communists invaded, many people panicked. In 1976, my grandparents, my mom, and I walked to the village of Pusongoi, where we thought we would be safe. Later that year, we fought communists who burned houses and were shooting in Pusongoi. We walked for 2 or 3 weeks to reach Mong Au. As we crossed to Mong Au, family members were protected by the villagers. Muong Cha, a city the size of Oshkosh, is close to Mong Au, where my mother is now living. Mong Au is close to the big city, but takes 1 day to walk. My mom remarried in 1978.

In 1980, the communists came again, shooting. At that time, every village in Laos was controlled by the communists, and we could not stay there; we just kept moving. The villagers moved to the jungle. In the jungle, there was no food, no rice, no anything. I was 10 years old and have strong memories ofthistime. We stayed hidden under the trees and banana leaves. The quiet and not knowing what was going to happen was scary.

We ate something like a potato which we dug out ot the ground with a knife. We also caught animals in something like a snare. We could only cook on cloudy days so that the smoke from the fires would not be discovered. There was no salt for cooking. At that time the salt was so expensive. You could buy an amount of salt the size of a quarter for 1 ghee, which was worth about $12. We could stay in one place in the jungle for about 1 week before all the food was gone. Before moving on, we would have to put everything back (ground cover) so as not to reveal our presence to the communists. We had to move because if we didn't, they would know the place where we were living.

They (communists) used low airplanes to locate us. If they saw smoke, they would shoot on the ground. The soldiers in the planes would call the s...