eBook - ePub

State and Social Welfare, The

The Objectives of Policy

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Aims to review the issues raised by the state provision of social benefits and to examine the principles on which their provision may be deemed to rest.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access State and Social Welfare, The by Dorothy Wilson, Dorothy Wilson,Thomas Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Debate about Social Policy

1 Social Policy: Issues and Objectives

Thomas and Dorothy Wilson

1.1 The Need for an Inquiry

'To be blunt the British social security system has lost its way',1 This opening observation in an official Green Paper on the need for reform echoes the sense of disillusionment often expressed in Britain, as in other developed countries with lengthy experience of the social security and other policies loosely comprehended by the term 'the welfare state'. Although various reforms have been carried out, dissatisfaction remains. Welfare expenditure is immense. If attention is confined to cash benefits, which constitute the social security system, to the health service and to the personal social services, Britain's annual public expenditure corresponds to over a fifth of gross national product. One person in two at any one time is in receipt of a cash benefit of some kind. Yet this vast ouday does not seem sufficient. Even the protection against want seems inadequate with large numbers still living 'in poverty', in some sense of that admittedly ambiguous term. There has been a similar disappointment in the failure to meet the full 'need' for health services, education and housing. These various failures have often been explained by saying that, although much has been spent, still more is required. Or it may be held that the means adopted for implementing welfare policies have been seriously defective and vulnerable to manipulation by special interest groups. It is also possible that the disillusionment may reflect obscurity and ambiguity in the objectives themselves and thus in the criteria by which success or failure have been determined. Or — a very likely explanation — there may be a conflict between objectives which has resulted in unsatisfactory compromises. Whatever the explanation, the difficulties and the dissatisfaction are not to be regarded as peculiarly British, for this is the common experience throughout the developed world. A striking example is the Swedish social security system - often held up as a model of its kind where serious problems are being encountered in sustaining its towering edifice of pensions (Ch. 11). In other European countries, and in North America, there are similar problems.

The need for a fresh assessment had already become increasingly clear after the oil crises of the 1970s had marked the end of a period of well-sustained and reasonably steady economic expansion. During that earlier period support for the welfare services seemed so widespread in Britain and elsewhere as to come close to a consensus, even if the 'rediscovery of poverty' in Britain in the 1960s — or its redefinition — had the effect of damping an earlier pride in the achievements. The moral widely drawn was not that a false start had been made but that faster progress along the same path was socially desirable. This was the period of 'incrementalism' which was brought to an end by the change in economic conditions and prospects. The central emphasis placed on inflation was then bound to be echoed in concern about the growth of public expenditure. Although the rise in output was subsequendy resumed and unemployment reduced from the high levels of the early 1980s, the confidence of previous decades had not been fully restored before the troubles of the 1990s began. It might be over-dramatic to talk of a crisis in the welfare state but the prospects for the new decade must be viewed with caution.

Admittedly the previous consensus was not so complete as to exclude differences of opinion about the scope and scale of the various benefits and services. Thus within government there was an unsuccessful attempt to achieve economies in public expenditure on the social services in 1955-57.2 Although the need for a fresh look at objectives was then incidentally acknowledged by some of the participants, this did not take place. Subsequently, the divergence of opinion has widened and deepened, and the future of social policy has become a party political issue in Britain to an extent not previously experienced since the end of the Second World War, The fact remains that expenditure in real terms rose substantially under Conservative governments — by almost a third on health and personal social services between 1979/80 and 1989/90, by almost a third on social security and by over a tenth on education and science. The widespread belief that the welfare state has been hacked away may be at least as much a reflection of the hostile rhetoric directed against 'welfarism' as it is a reflection of apparently hostile action. For the measures actually adopted since 1979 have, in fact, been mainly concerned to contain the rate of growth of expenditure in real terms rather than to reduce it absolutely. Even so, some acute shortages have been felt because rising demand has outstripped the constrained rise in supply. This has been notably the case in the health service, where advances in medical science and increases in the number of elderly people have laid heavy claims upon it in addition to large increases in the pay of its staff. The persistence of waiting lists for operations, together with the very visible closing of hospital wards, has been partly a consequence of the greater rise in costs relative to output than in the economy as a whole — the 'relative price effect'. In the case of cash benefits, the growth in the number of pensioners, the unemployed and single-parent families accounted for much of the increase in real expenditure, for there was no increase in real benefits per head after 1982. The severe cut by two-thirds in public expenditure on housing did, indeed, reflect a large-scale change in policy. Not least important, the introduction of the poll tax in 1990 was widely taken to indicate insensitivity to social welfare. For reasons such as these, another shift of emphasis seems to have taken place in British opinion with the stress increasingly laid on the need for a more 'caring' society.

However, more 'caring' may mean higher taxes or some cutting back of other claims on public resources. These other claims are large and some have become increasingly urgent - including the demand for greater effort to protect the environment. Unfortunately the growing pressure for more public expenditure of all kinds has come at a time when the weaknesses of the British economy have once more become painfully clear. The constraints are likely to be disagreeably tight. Apart from competition between claims made for the welfare state and those made for other public measures, there is also competition between the various services loosely grouped together as 'the welfare state'. Moreover, if so much expenditure has apparently produced such disappointing results can it be sensible simply to spend more? What objectives is all the effort designed to achieve?

1.2 Social Ideals and Social Pressures

A factual account of the objectives behind the welfare services would seek to explain how the various services were introduced and how their subsequent development took place. The objectives thus investigated would be those of the politicians, administrators, pressure groups and public-spirited persons or organisations by whose combined, though sometimes conflicting, efforts the outcome had been determined.3 Their aims will have been diverse, and this diversity will be reflected in the various social measures that have emerged. The task of the social historian is then to identify the various pressures, to trace their effects and to assess their importance. A different path may, however, be taken. For an inquiry can be made into the consequences to be expected from certain basic behavioural assumptions that are themselves believed to be firmly based on fact. This is the deductive method of the economic theory of politics or the theory of public choice.4 Politicians pursue votes, officials seek to advance their self-interest by defending and expanding their bureaucratic empires, powerful interest groups are at work. And so on. It is an old theme freshly presented.

By contrast, in the 'normative' approach, well-informed but disinterested persons seek to prescribe the measures that are, in their view, most likely to contribute to social welfare. These investigators may disentangle moral value judgements from more technical scientific propositions with varying degrees of punctiliousness and success, and a variety of different recommendations for the promotion of social welfare will emerge. But although a philosopher king — or a William Beveridge — may design a scheme with a coherent conception of social welfare in mind, his creation will be subjected to the force of the vote motive and something substantially different may then emerge. 'Ideas' may succumb to 'interests'.

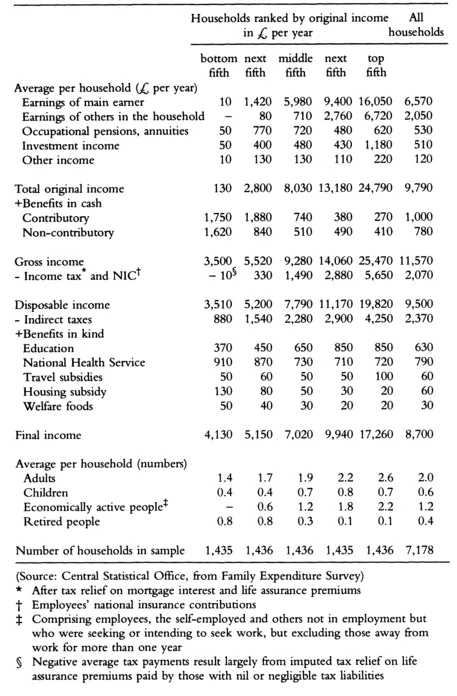

A particularly strong expression of scepticism about the outcome for social welfare is contained in the assertion that the 'welfare state' has been hijacked by the middle class, with the result that it is they, not the workers, who benefit. The Far Left and the Far Right have joined forces in this attack — the former because they wish to discredit 'reformist capitalism', the latter because they fear that such reforms will destroy capitalism. That there is some substance in this assessment may be conceded at once but it is exaggerated. Although attempts to calculate the net redistributive effects must be hedged with reservations — not least about the elusive incidence of taxation — the official statistical estimates do not support the view that it is the lower income group that benefits least from the tax/benefit system in Britain (see Table 1.1).

1.3 The Objectives of Policy — An Interim Statement

The objectives of social security in Britain were presented with particular clarity by Beveridge in 1942. He surveyed a range of circumstances - such as old age and unemployment — in which benefits seemed appropriate and then put forward a comprehensive scheme which would apply consistent principles throughout. This unified structure, broadly adopted by government in 1948, became a special feature of the British arrangements which contrasted with those in other countries where different benefits — such as pensions and unemployment pay - have been financed in different ways and provided at different rates by different agencies. The central objective of the British system was protection against poverty on a scale to be uniformly applied. It is true that Beveridge did not deal adequately with the situation of the working poor, and it is also true that his proposals were not fully implemented. Moreover, various changes have subsequently been made over the years which have introduced additional complications. When therefore the new official review of social security was carried out in 1985, it differed in coverage and detail from the old Beveridge Report. The fact remains that the central emphasis was still placed on protection against poverty. This continues to be so to a greater extent than in other European countries or in the USA.

The provision of a minimum income as a safety net — sometimes opprobiously described as the 'minimalist principle' — may have the appearance of at least being simple and straightforward. This appearance is deceptive. The ambiguity of the term 'poverty' is a warning of the difficulties ahead. Thus as the poverty level is raised, in an increasingly affluent society, the emphasis shifts from 'subsistence' to 'social solidarity' and 'the ability to participate in

Table 1.1 Redistribution of income in the UK through taxes and benefits, 1986

the life of the community'. In effect, the aim of providing protection against poverty may be gradually merged with the aim of reducing inequality. It may indeed be pointed out that some measure of redistribution has always been an obvious feature of any scheme in which benefits are provided to the retired, the unemployed and the sick at the expense of those who are currently at work. But these beneficiaries will themselves have contributed in their active years and it cannot be simply taken for granted that, in the longer run, a vertical life-time transfer between rich and poor has taken place.

A social security system that is designed to provide protection against poverty can appeal to altruism or to a regard for fairness, but it is more difficult to find a satisfactory moral basis for graduated pensions related to previous income when at work. The aim is said to be 'income-maintenance' and it is, of course, only natural that retired people should wish to have incomes that are some tolerable proportion of what they received in their working years. But it is not immediately apparent that a state scheme, backed by compulsion, is required. Yet income-related pensions have been common throughout the developed world with Britain and Australia as the main exceptions, until Britain too fell into line for reasons to be investigated in a later section.

The egalitarian theme is resumed in a consideration of benefits in kind — such as the health service. These benefits may seem to lie outside the scope of social security systems concerned with cash transfers, but it would clearly be impossible to consider the adequacy of these transfers without taking into account the free or heavily subsidised provision of benefits in kind. (For example, if this is not done, misleading conclusions may be drawn from comparisons of cash transfers in Britain with those m some other countries.) Moreover, it is highly relevant to ask why some benefits should be in kind, for this imposes a restraint on the citizen's freedom of choice. Thus the paternalism which is a feature of the welfare state as a whole is more marked in the case of benefits in kind.

It is not only the nature and scale of the social benefits that must be viewed in the light of social objectives but also the manner in which these benefits are delivered. Here too value judgements conflict. Whereas liberals may insist that the paternalism behind benefits in kind requires special explanation and defence, collectivists may insist that the social uniformity thus imposed is an appropriate and desirable expression of social solidarity. Hence the insistence that the same health service should be available to everyone in the same way and, furthermore, that the service should be not only fully financed by the state but also supplied by an agency of the state. For the market is held to be the domain where self-interest prevails, and that domain should be, if not abolished, at least restricted in scope by the communal provision of social benefits. Moreover, where a 'gift relationship' is possible it should be preferred to a 'cash relationship'. The most usual example is that of blood which, Titmuss held, should be donated free to hospitals, not put up for sale.5

A great deal has also been said about the effect on personal dignity and self-reliance of the way in which cash benefits are provided. Selectivity by means test has long been criticised, but means tests have the offsetting merit of targeting benefits towards those in need. We are touching here on one of the most difficult policy dilemmas in this field.

Even these preliminary observations suggest that conflicts between different objectives are bound to arise and it may well be that the disillusionment sometimes expressed about the welfare state is a consequence of confining attention to one or other of these aims to the neglect of others. Thus, as well as the possible conflicts already implied in what has been said above, there is a further conflict between simplicity in administration and sensitivity in meeting diverse individual requirements. Yet another social objective that may, perhaps, receive too little attention f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- PART ONE THE DEBATE ABOUT SOCIAL POLICY

- PART TWO QUESTIONS OF PRINCIPLE

- PART THREE QUESTIONS OF PRACTICE

- PART FOUR SOME ISSUES OF POLICY IN EUROPE

- PART FIVE SHAPING THE COURSE OF POLICY

- Appendix: Social Security in the UK

- Index