![]()

Chapter

1

Introduction

In a little more than a decade, traffic calming has entered the transportation planning and engineering mainstream. The earliest U.S. programs, established in the 1970s, were anomalies. They had limited toolboxes of traffic calming measures and ad hoc policies operating under titles such as “neighborhood traffic management” and “residential speed control.” As recently as 1992, the broader concept of traffic calming was virtually unknown in the United States, and annual meetings of the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) featured one or two papers in the general subject area. A mere five years later, the board of directors of ITE had adopted traffic calming as an institute priority, entire sessions at ITE meetings were devoted to the topic, dozens of programs had been established around the United States, and a state-of-the-practice guide had been written for ITE and the Federal Highway Administration.

This U.S. Traffic Calming Manual represents a milestone in the evolution of traffic calming in the United States. It is the first complete how-to manual developed in this country. It is based in part on the first traffic calming manual taken through a formal rule-making process and adopted by a state department of transportation (Delaware’s) as a supplement to its roadway design manual. (See p. 3, below.) It has been modified by many local jurisdictions (including Anchorage, Charlotte, Denver, Ithaca, Sacramento, and San Diego) to match local priorities and preferences. (See p. 9, below.)

From this manual, professional engineers and planners will receive general guidance on the appropriate use, design, and signing and marking of traffic calming measures. Local officials, developers, community associations, and other interested parties will learn what traffic calming is and how it can be applied.

1.1 Definition of Traffic Calming

This manual is a companion to (and shares authorship with) the Institute of Transportation Engineers report, Traffic Calming: State of the Practice (Figure 1-1). That report defines traffic calming as follows:

traffic calming involves changes in street alignment, installation of barriers, and other physical measures to reduce traffic speeds and/or cut-through volumes, in the interest of street safety, livability, and other public purposes.1

The ITE definition emphasizes the use of physical measures to slow or divert traffic. The definition excludes nonengineering measures that may improve street appearance, assuage residents’ concerns about traffic, or in some cases even affect traffic volumes and speeds. Planting trees on a roadside, enforcing traffic laws more intensively, or running neighborhood traffic-safety campaigns may all be worthwhile for other reasons. However, according to Traffic Calming: State of the Practice (Chapter 5), they cannot be counted on to slow or divert traffic.

The ITE definition emphasizes the ultimate purposes of traffic calming. Traffic speeds or volumes are reduced as a means to other ends, such as improving the quality of life in residential areas, increasing

Figure 1-1. Traffic Calming: State of the Practice

Origin of This Manual

The U.S. Traffic Calming Manual evolved from a design manual prepared for and adopted by the Delaware Department of Transportation (DelDOT).

Prior to the creation of that manual, DelDOT’s responses to citizen requests for traffic calming had been ad hoc and sometimes, under pressure to “do something,” misguided. For example, the test closure of a residential collector carrying 18,000 vehicles per day (vpd) showed that roads at this level in Delaware’s functional hierarchy must be calmed in other ways, since with the closure, traffic was diverted to local streets less capable of handling it. The road was reopened and ultimately treated with a series of chicanelike devices. (See Figure 1-2.)

The installation of rough surface material on another residential collector carrying 10,000 vpd did little to slow traffic. The road was a critical emergency-response route and so could not be traffic calmed in more conventional ways. But the compromise treatment only created noise problems for adjacent residents, who eventually demanded that the surface material be removed. (See Figure 1-3.)

The profile of speed humps on a third Delaware street was such that discomfort decreased with increasing speed, the reverse of what is necessary for speed control. The profile appeared to be more triangular, and less circular, than conventional humps. Lack of standardization was responsible for this problem.

Figure 1-2. Successful Chicanelike Device on an 18,000 vpd Collector Road (Newark, Del.)

Such experiences prompted DelDOT to commission its manual, which was taken through the rule-making process and formally adopted as a supplement to Delaware’s Road Design Manual. The pioneering nature of this effort caused DelDOT to be conservative in its policies, which may be revisited and revised after more experience.

Figure 1-3. Unsuccessful Surface Treatment Being Removed from a 10,000 vpd Collector Road (The Ardens, Del.)

The DelDOT manual and the guidelines it contains apply to all streets and highways under state jurisdiction, including existing and new numbered state routes and existing and new subdivision streets maintained by DelDOT. An estimated 88 percent of all streets and highways in Delaware fall under state control. Many minor streets, which in other states would be under city or county control, are under state control. These streets are particularly good candidates for traffic calming, making the adoption of statewide policies all the more critical in Delaware.

walking safety in commercial areas, or making bicycling more comfortable on commuter routes. Not all roads are suitable for traffic calming. This manual distinguishes between cases where traffic calming is warranted and those where it is not.

1.2 Federal and State Initiatives

Nationally, traffic calming is part of a sea change in the way transportation systems are viewed. With passage of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA), transportation planning and engineering became more multimodal and sensitive to the social costs of automobile use. Our once single-minded pursuit of speed and capacity became tempered by other concerns. The legislative successor to ISTEA, the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21), continued and expanded ISTEA programs and created a multimillion-dollar pilot program for “Transportation and Community and System Preservation,” under which traffic calming projects became eligible for federal funding. Two large traffic calming projects received earmarked funding elsewhere in TEA-21. The latest surface-transportation act, called the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users of 2003 (SAFETY-LU), makes traffic calming eligible for funding under the Highway Safety Improvement Program and the Safe Routes to School Program.

Figure 1-4. Handbook on Traffic Calming (Pennsylvania DOT)

The state role in traffic calming has also grown in recent years. In the United States, traffic calming is usually limited to local and collector streets, and such streets generally fall under the jurisdiction of local governments. State departments of transportation (DOTs) may promote traffic calming through technical-assistance activities, but they generally do not treat roads themselves. The State of Pennsylvania has an illustrated handbook on the subject. (See Figure 1-4.) Massachusetts and New York have adopted traffic calming guidelines, and California has made traffic calming eligible for funding under its Safe Routes to School program. Several states have offered training programs aimed at local traffic engineers.

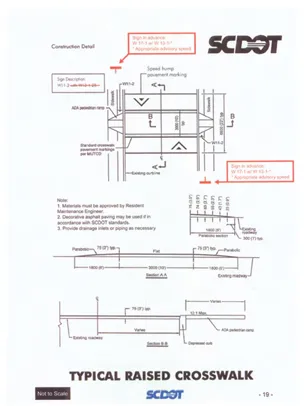

In the few states that do own and operate local and collector roads, there has been actual implementation activity. South Carolina and Virginia have adopted typical designs for traffic calming measures (see Figure 1-5), and the State of Delaware has a complete design manual.

In an important new development, the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO), representing state DOTs, has endorsed traffic calming on certain state highways and streets. “Traffic calming techniques may apply on arterials, collectors, or local streets. . . . Traffic calming aimed at reducing speeds is primarily used in lower speed urban areas and in speed transition areas such as near the urbanized limits of small towns.”2

Figure 1-5. Typical Raised Crosswalk Design (South Carolina DOT)

1.3 Local Trends

At the local level, traffic calming has expanded from a few scattered programs with limited scopes and toolboxes to a mainstream activity of transportation engineering. The website www.trafficcalming.org has links to programs in 159 jurisdictions. A recent Internet search uncovered an additional 51 programs, and for every one of these there are probably several more operating anonymously.

A 2004 survey of 20 leading jurisdictions found that the field has matured considerably since the 1999 Traffic Calming: State of the Practice.3 Some of the most significant changes are: mainstreaming...