![]()

Measuring energy consumption

Energy savings cannot be made on a sustainable basis without appreciation of where energy is being used, for what reason, and what might be influencing consumption patterns. This chapter moves from a basic discussion of how energy is used, through conducting an energy audit, to techniques for regular energy measurement and monitoring. All of this is a prelude to identifying excessive energy use, consequent potential energy conservation measures, and a full measurement and verification (M&V) plan.

Energy units

Energy is described using several different units. The SI unit of energy is the joule. Other units of energy include the kilowatt-hour (kWh) and the British thermal unit (Btu). These are both larger units of energy. One kWh is equivalent to exactly 3.6 million joules, and one Btu is equivalent to about 1,055 joules. Full conversion tables are given in the Appendix at the back of the book, together with tables converting fossil fuel energy use into greenhouse gas emissions and other vital information. These are necessary to convert energy use in different contexts to the same units for calculations.

Energy sources

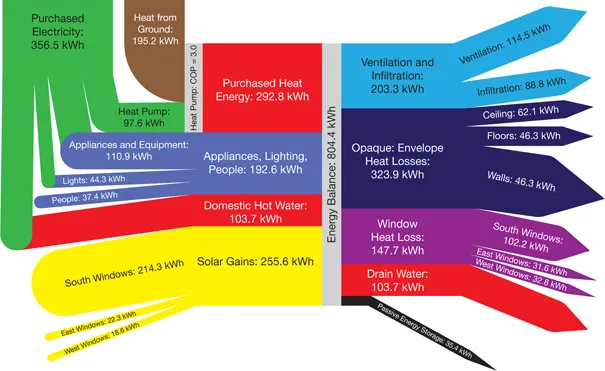

Energy arrives in a building or facility from many directions: from direct sunshine, from an electricity supply, from fuels such as gas and oil which are burned for heating or to create movement, and from heat arising from activities and processes. Energy is used in many ways: for space heating and cooling, for water heating and process heat, for lighting and equipment such as motors, fans, PCs and chillers, for industrial processes and for transport.

Energy efficiency

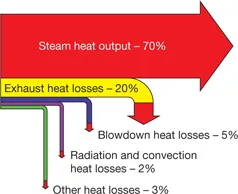

Efficiency is measured by the amount of useful work conducted by the energy supplied as it is converted into power. The energy which is wasted in this process appears as heat. This is why LED lighting is so much more efficient: incandescent lighting gives off a lot of heat, which is wasted energy, while LEDs do not. Similarly, an industrial gas-powered electricity generator will lose 70 per cent of the energy content of the gas as heat unless it is burnt in a combined heat and power generator, which reclaims a further 30 to 60 per cent of the heat.

Energy never disappears when used; it just becomes converted into another form. Eventually, it all becomes heat. It is absorbed into the fabric of the building and equipment, then filters into the environment. It is a general rule that in any system, energy in equals energy out, but before it finally dissipates some of this energy may be reclaimed and reused, or stored in hot water tanks or in batteries, or as hydrogen. Some heat may often be reclaimed from generators and boilers, as we will see in Chapter 5, but there is a natural limit to this process. Sometimes heat generated by equipment is unwanted, as with fridges; an extreme case of this is in data centres, which are discussed in Chapter 11.

The following are the definitions of efficiency for different types of energy use:

● electrical: useful power output per electrical power consumed;

● mechanical: the proportion of one form of mechanical energy (e.g. potential energy of water) that is converted to mechanical energy (work);

● thermal or fuel: the useful heat and/or work output per unit of fuel or energy consumed;

● lighting: the proportion of the emitted electromagnetic radiation usable for human vision;

● total efficiency: the useful electric power and heat output per fuel energy consumed.

Figure 1.1 Diagam showing the energy balance of a hypothetical building. Sources of energy entering are on the left, and ways in which it leaves are on the right. The total energy balance is quantified in the centre.

Source: ‘Preliminary Investigation of the Use of Sankey Diagrams to Enhance Building Performance Simulation-Supported Design’, William (Liam) O'Brien of Carleton University, Ottawa.

Figure 1.2 Diagram showing the heat losses from a non-condensing boiler. All processes lose energy as heat.

Source: Author

It often makes sense to talk about the efficiency of an entire system or process, such as how much electricity is consumed to produce 1,000 widgets. It is extremely important to be clear on the units that are being used and the type of efficiency that is being measured; otherwise confusion may result. For example, there is a difference between Europe and America in the definition of heating value. In the US and elsewhere, the usable energy content of fuel is typically calculated using the higher heating value (HHV), which includes the latent heat for condensing the water vapour emitted by burning the fuel. In Europe, it is the convention to use the lower heating value (LHV) of that fuel, which assumes that the water vapour remains gaseous and is not condensed to liquid water, so releasing its latent heat. Using the LHV, a condensing boiler, which makes use of this latent heat, can achieve a ‘heating efficiency’ in excess of 100 per cent, whereas, of course, using HHV, this efficiency is around 90 per cent, compared to 70 to 80 per cent for non-condensing boilers.

The aim of energy management is to improve the overall efficiency of the entire systems for which the manager is responsible: to get more work out for the energy put in, and certainly to make use of the free energy that is available, principally from the sun. In calculations to determine building efficiency strategies, when this free energy is called ‘passive gains’, it needs to be taken into account.

Energy audits

A European and world standard for energy audits, published in October 2012, BS EN 16247–1, explains the process of conducting an energy audit in great detail, defining the attributes of a good-quality energy audit, from clarifying the best approach in terms of scope, aims and thoroughness to ensuring clarity and transparency. It specifies the requirements, common methodology and deliverables for energy audits. It applies to all forms of establishments and organisations, all forms of energy and uses of energy, excluding individual private dwellings, and is appropriate to all organisations regardless of size or industry sector. It was developed by members of ESTA (the Energy Services and Technology Association), the Energy Institute, Institute of Chemical Engineers, and Energy Services and Technology Association in Britain, in response to the 2006 EU Directive and in anticipation of the Energy Efficiency Directive. This mandates member countries to create regular energy audits for large organisations. It complements the energy management system standard ISO 50001:2011 which identifies the need for clear energy auditing. At the time of writing, further, more specific standards are being developed but will be available shortly: energy audits for Buildings (EN 16247–2), Processes (EN 16247–3) and Transport (EN 16247–4).

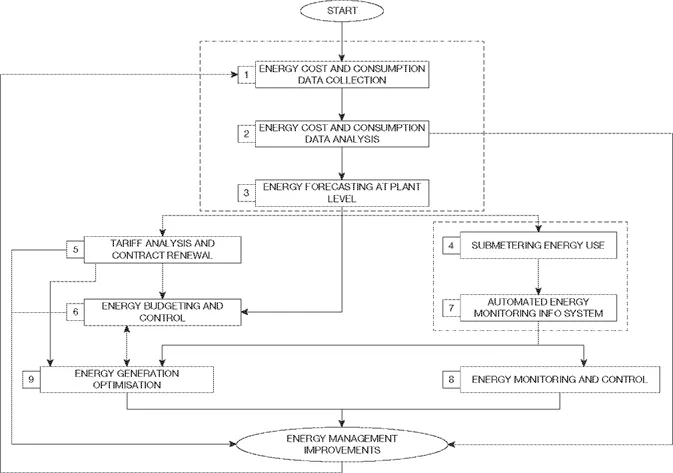

Figure 1.3 The process of auditing, benchmarking and performance optimising.

Source: Carbon Trust

The first step of an energy audit is to discover where all the energy comes from and where it goes, and to quantify this. It may then be compared to an established benchmark of energy use for the building, company, organisation or ...