eBook - ePub

Affect, Cognition and Change

Re-Modelling Depressive Thought

- 285 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This text, a collaboration between a clinical psychologist and a cognitive psychologist, offers a cognitive account of depression.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Affect, Cognition and Change by Philip Barnard,John Teasdale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

The Problem; Some Evidence; Previous Answers

CHAPTER ONE

Negative Thinking and Depression

A young woman is walking her dog. It is a beautiful September morning. It is her birthday. She is very aware of her thoughts: “What a flop my life has been all these years—another rotten year gone and lots more to go—how full of failures and miseries my life has been.”

She is depressed. Is this the reason she thinks in this gloomy pessimistic way, or has her life really been so bad? Does thinking this way contribute to keeping her depressed? If we were to change the way she thinks would this change the way she feels? If we were to change the way she feels would this change the way she thinks? Can we, by changing the way she thinks and feels, help reduce the chances that she will continue to be depressed, both now and in the future?

These questions provided the stimulus to the enquiry of which this book is a part. The answers are likely to be of more than theoretical interest. Cognitive models of depression (Beck, 1976) suggest that negative pessimistic thinking is an important factor maintaining depression. Cognitive therapy, a form of psychological treatment based on these ideas, is designed to teach patients to change the way they think and feel. This psychological therapy has already been shown to be at least as effective as tricyclic antidepressant medication in the treatment of outpatients with major depressive disorder. There is also encouraging evidence that cognitive therapy is more effective than pharmacotherapy in preventing future relapse, once initial treatment has been discontinued (Hollon, Shelton, & Loosen, 1991; Williams, 1992). Cognitive therapy is currently quite complex and time-consuming. Better understanding of the psychological processes involved in the maintenance and modification of depression is likely to be an important factor in the further development of improved methods of psychological treatment. More generally, it is likely that the attempt to understand the processes involved in maintaining and changing depression will cast light on the wider range of mild unpleasant mood states that afflict us all from time to time.

An Overview:

The Applied Science Approach to Understanding Depressive Thinking

Our general strategy is to adopt an applied science approach. This provides a method by which practical problems can be solved while, at the same time, basic psychological understanding is advanced. This strategy takes a concrete “real-world” problem as an initial point of departure, and as a continuing reference point against which the relevance of subsequent experimentation and theorisation can be gauged. It then exploits existing investigative paradigms, or creates new paradigms, to capture in the laboratory essential aspects of the applied problem. Taking advantage of the precision of measurement and the power of experimental methodology offered by these laboratory paradigms, theoretical accounts of experimentally demonstrated phenomena are developed. These theories can then be applied and refined by reference both to the initial “real-world” problem, and to continuing laboratory investigations designed to test key features of the theories. By a continuing iterative interaction between experiment, theory, and attempts to solve the applied problem, more detailed empirical information is accumulated and theoretical accounts are improved. The eventual outcome is that our ability to deal with the practical target problem is improved, and we also have a clearer understanding of related aspects of psychological function, rooted in controlled empirical investigations.

In this book we focus on the problem of the negative thinking shown by depressed patients, its possible role in the production and maintenance of depression, and how, by changing this thinking, or processes associated with it, we can improve psychological treatments for depression. We begin by considering the cognitive model of depression, developed by clinicians from their astute observation of depressed patients. Although not couched in precise scientific terms, these ideas have been invaluable in developing effective psychological treatments for depression. However, these ideas, in their original form, have encountered considerable difficulties as more detailed evidence has accumulated. Further, the effectiveness of treatments based on these ideas, although encouraging, still leaves room for improvement. Thus, there is reason to look to the applied science strategy to see whether it can provide better understanding of depressive thinking, and guidelines for the development of further improvements in treatment. We describe the application of this strategy, drawing both on our own work and that of others.

We describe the development of the applied science approach to depressive thinking in approximate chronological order. The first stage involved empirical investigation of aspects of information-processing in depressed patients, and in normal subjects in whom depressed mood had been induced experimentally. The findings of these studies provided the challenge to develop explanatory theoretical accounts. Gordon Bower’s associative network theory of mood and memory offered an initially attractive and useful way of understanding the results of these and many related studies. We describe and evaluate this approach. Application of Bower’s theory to the problem of depression overcomes many of the difficulties encountered by the original, clinically derived, accounts and provides valuable new insights into the clinical problem.

A virtue of experimentally derived theories is that their precision enables their weaknesses to be identified. As more and more experimental evidence of the effects of moods on cognitive processes has accumulated, it has become increasingly clear that Bower’s associative network theory is inadequate. Interestingly, some of the difficulties of this theory, recognised by cognitive psychologists, parallel difficulties with the clinically derived cognitive model recognised by cognitive therapists.

Problems at both the experimental and clinical levels are resolved in an alternative conceptual framework, Interacting Cognitive Subsystems (ICS). As this is a relatively novel approach it is presented in some detail. Unlike both the clinical cognitive model and Bower’s associative network theory, which recognise only one specific level of meaning, ICS recognises both a specific and a more holistic, generic, level of meaning. ICS suggests that affect is directly related only to the more generic level of meaning. ICS enables us to capture, within an explicit information-processing framework, the distinction between “knowing with the head” and “knowing with the heart”.

The application of ICS to understanding mood-related biases in memory and judgement is described. The proposal that such biases arise from the effects of affect-related schematic models allows ICS to provide an integrative account of existing empirical evidence in these areas. In the course of accounting for the variability of experimental results in laboratory studies of mood and memory, the ICS analysis offers new insights into the nature of moods themselves.

The analysis of mood-related biases in memory and judgement provides the basis for an account of negative depressive thinking and its role in the maintenance of depression. The suggestion that information-processing can become “interlocked” in vicious cycles, processing only a limited range of depressive themes, is central to this account. The account is wholly consistent with the empirical evidence available in this area. The motivational bases of “interlocked” patterns of cognitive processing are explored in relation to self-regulatory theories of depression. The analysis that emerges suggests that such processing reflects attempts to resolve discrepancies in situations where centrally important goals can neither be attained nor relinquished.

The ICS account of negative thinking and depression is compared with that offered by Beck’s clinical cognitive model. In contrast to the initial formulations of the clinical model, ICS emphasises the importance of higher-level meanings, associated with the processing of affect-related schematic models. These models integrate sensory contributions, particularly those derived from bodily experience, with patterns of lower-level meanings. The processing of schematic models is marked by the subjective experience of “felt senses” with implicit meaning content.

Interacting Cognitive Subsystems provides a comprehensive framework within which we can understand the effectiveness not only of existing, standard, forms of cognitive therapy for depression but also of more recent developments in cognitive therapy, and of a range of other psychological treatments. ICS provides an explicit account within which the strengths of earlier statements of the clinical cognitive model, and of conventional forms of cognitive therapy, can be retained while at the same time acknowledging the contribution of more recent developments. In this way, ICS can provide a theoretical foundation for achieving further progress in improving psychological treatments. In particular, ICS provides an information-processing framework within which accounts of experientially oriented treatments can be developed.

The book concludes with a discussion of ways of improving our understanding of complex phenomena such as the inter-relationship between cognitive and affective processes. A virtue of the Interacting Cognitive Subsystems approach presented is that it is, potentially, a conceptual framework that we can use to understand not only experimental and clinical phenomena, but also ourselves.

Negative Thinking and Depression:

Beck’s Original View

Systematic studies demonstrate that patterns of negative thinking are a very common characteristic of depressed people in general, not just of our young lady walking her dog. On the basis of clinical observation, Beck (1967; 1976) identified a pattern of reportable depressive thoughts, which he termed the negative cognitive triad. This consists of a negative view of the self (perceived as deficient, inadequate, or unworthy), of the world (interactions with the environment are perceived as representing defeat or deprivation), and of the future (current difficulties or suffering will continue indefinitely). Studies employing quantitative measures have generally confirmed the existence of these patterns of thinking in depressed samples (e.g. Haaga, Dyck, & Ernst, 1991).

Beck (1967; 1976; 1983) and his colleagues (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Beck, Epstein, & Harrison, 1983; Kovacs & Beck, 1978) have outlined a theoretical account of the origins and role of negative thinking in the aetiology of depression. These ideas have had enormous influence in shaping treatment and research in depression. Before presenting and evaluating this account it should be pointed out that it is, avowedly, a clinical rather than a scientific theory. By this, its proponents mean that the main purpose of the theory is to guide the clinician in understanding and treating patients, rather than to provide a detailed exposition articulated in precise theoretical terms. It has, nonetheless, generated a considerable body of research and controversy (e.g. Coyne & Gotlib, 1983).

A major difficulty in evaluating Beck’s cognitive model stems from the fact that it is a clinical theory. Consequently, presentations of the model have tended to be relatively imprecise, to have varied from one statement to another, and to have shifted in their emphasis over time. We present and evaluate what is generally regarded as the “original” version of the cognitive model, citing original sources wherever possible. In doing so, it is important to acknowledge that there have been subsequent developments in the corpus of ideas subsumed within the clinical cognitive model. Some of these developments have, indeed, been in response to criticisms similar to those which we shall describe. Nonetheless, the “original” version of the model is still widely used, and, historically, was the form of the model prevailing at the time that our “narrative of applied science” begins.

“The cognitive model views the other signs and symptoms of the depressive syndrome as consequences of the activation of the negative cognitive patterns. For example, if the patient incorrectly thinks he is being rejected, he will react with the same negative affect (for example, sadness, anger) that occurs with actual rejection. If he erroneously believes he is a social outcast, he will feel lonely” (Beck et al., 1979, p. 11). This view suggests that negative cognitions produce depressed affect. Beck et al. (1979, pp. 12–13) define cognitions “as any ideation with verbal or pictorial content”. Similarly (Beck et al., 1983, p.2): “Cognitions are stream-of-consciousness or automatic thoughts that tend to be in an individual’s awareness … Examples of negative cognitions are ‘I’m a failure’, ‘No one will ever love me’, and ‘I’ve made a mess of my life’.” The use of the term “cognitions” in this way to refer solely to consciously experienced thoughts and images clearly diverges from the much wider use of the term in cognitive psychology, where it is assumed that the majority of cognitive processing is not experienced as consciously accessible thoughts or images. This difference in the use of terms has been the basis of a number of misunderstandings (e.g. see discussions by Lang, 1988; Leventhal & Scherer, 1987).

Where do the negative cognitions that produce depression come from?

In Beck’s cognitive model, distorted cognitions are produced when a stressful event (e.g. divorce, loss of a job) activates an individual’s unrealistic schemata … Schemata are … stable, general underlying beliefs and assumptions about the nature of the world and how one relates to it. These assumptions are based on past experience and serve to direct the individual’s attention to, and interpretation of, current experiences. Examples of schemata are ‘If I am not loved by others, I am not a worthwhile person’ and ‘I must achieve great things or I will be a failure in life’…. The person’s underlying assumptions constitute a vulnerability to events. (Beck et al., 1983, p. 2.)

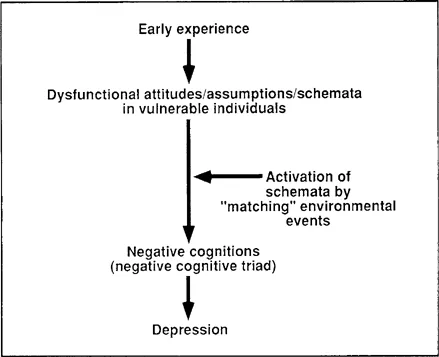

It is suggested that, in vulnerable individuals, negative cognitions arise from the application of dysfunctional assumptions to “matching” events, much as in the derivation of conclusions from premises in an argument (Kovacs & Beck, 1978, p. 528). So, for example, given the premise “If I am not loved by others, I am not a worthwhile person”, evidence of indifference by someone leads to the conclusion, expressed in a negative cognition, “I’m a failure”. This negative cognition in turn, it is proposed, leads to depressed affect. Figure 1.1 summarises the key features of the cognitive model of depression.

Problems with Beck’s Cognitive Model

As it has been investigated more closely, Beck’s cognitive model has encountered a number of difficulties. Some of these are summarised here.

1. Purely “cognitive” accounts of depression, and depressive thinking, are embarrassed by evidence suggesting that negative thinking may be a consequence of depression rather than anantecedent to depressed feelings. For example, most measures of negative thinking recover towards normal levels with remission of the episode of depression even when, as in treatment with antidepressant drugs, no attempt is made to deal with environmental events, negative cognitions, or dysfunctional beliefs or assumptions (Simons, Garfield, & Murphy, 1984). Similarly, when psychological treatments directed at changing behaviours or interpersonal processes, rather than cognition, are successful in reducing depression, they reduce negative thinking to an extent comparable to that achieved by equally effective treatments targeted on cognition (e.g. Imber et al., 1990; Rehm, Kaslow, & Rabin, 1987). It is difficult to reconcile such evidence with the view that negative thinking is solely an antecedent to depression. Rather, these findings suggest that negative thinking is, either as well or instead, a consequence of depression.

FIG. 1.1. Beck’s cognitive model of depression...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Part I The Problem; Some Evidence; Previous Answers

- Part II The Interacting Cognitive Subsystems (ICS) Approach

- Part III ICS and Mood-congruous Cognition in the Laboratory

- Part IV ICS, Negative Thinking, and the Maintenance of Depression

- Part V ICS, Depression, and Psychological Treatment

- Part VI Afterword

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index