eBook - ePub

Connectivity Conservation Management

A Global Guide

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Connectivity Conservation Management

A Global Guide

About this book

In an era of climate change, deforestation and massive habitat loss, we can no longer rely on parks and protected areas as isolated 'islands of wilderness' to conserve and protect vital biodiversity. Increasing connections are being considered and made between protected areas and 'connectivity' thinking has started to expand to the regional and even the continental scale to match the challenges of conserving biodiversity in the face of global environmental change. This groundbreaking book is the first guide to connectivity conservation management at local, regional and continental scales. Written by leading conservation and protected area management specialists under the auspices of the World Commission on Protected Areas of IUCN, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, this guide brings together a decade and a half of practice and covers all aspects of connectivity planning and management The book establishes a context for managing connectivity conservation and identifies large scale naturally interconnected areas as critical strategic and adaptive responses to climate change. The second section presents 25 rich and varied case studies from six of the eight biogeographic realms of Earth, including the Cape Floristic Region of Africa, the Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains, the Australian Alps to Atherton Corridor, and the Sacred Himalayan Landscape connectivity area (featuring Mount Everest.) The remarkable 3200 kilometre long Yellowstone to Yukon corridor of Canada and the United States of America is described in detail. The third section introduces a model for managing connectivity areas, shaped by input from IUCN workshops held in 2006 and 2008 and additional research. The final chapter identifies broad guidelines that need to be considered in undertaking connectivity conservation management prior to reinforcing the importance and urgency of this work. This handbook is a must have for all professionals in protected area management, conservation, land management and resource management from the field through senior management and policy. It is also an ideal reference for students and academics in geography, protected area management and from across the environmental and natural sciences, social sciences and landuse planning. Published with Wilburforce Foundation, WWF, ICIMOD, IUCN, WCPA, Australian Alps and The Nature Conservancy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Ciencias biológicasSubtopic

EcologíaPart I

Setting the Context

1

The Connectivity Conservation Imperative

Graeme L. Worboys

A remarkable conservation land-use revolution occurred at the end of the 20th century and start of the 21st century, with the number of protected areas (PAs) growing from approximately 40,000 in 1980 (Chape et al, 2008) to 113,959 in January 2008 (UNEP-WCMC, 2009). This achievement transpired in response to an international commitment to conserve a representative sample of the natural and cultural heritage of all countries. In the 1990s, in parallel with this effort, the need to conserve the connectivity of natural lands between protected areas also emerged. It had become increasingly evident to many that protected areas, in isolation, may not always be able to protect all of their biodiversity values. ‘Island’ protected areas were vulnerable to multiple threats, especially the consequences of climate change. A consensus emerged that biodiversity conservation required large-scale interconnected natural landscapes with embedded and interconnected protected areas.

By 2009, as evidence for human-induced climate change became more pronounced and as climate change modelling forecasts demonstrated the ramifications of changes to species and habitats, the interest in connectivity conservation had grown. Scientists such as Andrew Bennett identified the importance of these large-scale connectivity conservation areas:

linkages also have a role in countering climate change by interconnecting existing reserves and protected areas in order to maximise the resilience of the present conservation network. Those linkages [connectivity conservation areas] that maintain large contiguous habitats or that maintain continuity of several reserves along an environmental gradient are likely to be most valuable in this regard (Bennett, 2003).

This book is about managing terrestrial connectivity conservation areas like those described by Bennett. Its primary purpose is to help conserve nature and species on Earth for the long term. Its primary focus is on how to establish and manage these large-scale essentially natural lands to achieve conservation outcomes. It does this by introducing the foundational concepts of connectivity conservation, communicating the experiences and wisdom of connectivity managers, developing a conceptual framework and describing the processes and tasks of connectivity conservation management.

About connectivity conservation

So what exactly is connectivity conservation and what are the common terms that are used in this book? The concept of connectivity described here is based on the biological sciences. Its focus is purely terrestrial (although connectivity conservation is an equally important conservation need for marine environments and deserves similar treatment). Natural connectivity for species in the landscape has a structural component, which relates to the spatial arrangement of habitat or other elements in the landscape, and it has a functional (or behavioural) component, which relates to the behavioural responses of individuals, species or ecological processes to the physical structure of the landscape (Crooks and Sanjayan, 2006b). This description has been refined further to recognize four types of connectivity:

1 Landscape connectivity, which is a human view of the connectedness of patterns of vegetation cover within a landscape (Lindenmayer and Fischer, 2006).

2 Habitat connectivity, which is the connectedness between patches of habitat that are suitable for a particular species (Lindenmayer and Fischer, 2006).

3 Ecological connectivity, which is the connectedness of ecological processes across many scales and includes processes relating to trophic relationships, disturbance processes and hydro-ecological flows (Lindenmayer and Fischer, 2006; Soulé et al, 2006).

4 Evolutionary process connectivity, which identifies that natural evolutionary processes, including genetic differentiation and evolutionary diversification of populations, need suitable habitat on a large scale and connectivity to permit gene flow and range expansion – ultimately, evolutionary processes require the movement of species over long distances (Soulé et al, 2006).

The concept of landscape connectivity recognizes that while there may be a continuum of vegetated landscape, it may not include suitable habitat for specific species. There are features that contribute to landscape connectivity and these include wildlife corridors, stepping stones and a matrix of vegetation that has similar attributes to patches of native vegetation (Bennett, 2003; Lindenmayer and Fischer, 2006). It may also involve the conservation of ecological connectivity between lands that are spatially separated. The scientific aspects of connectivity and the language used are discussed in Chapter 2.

The conservation of connectivity is our next consideration. Active conservation involves people and this is where we extend our concept of connectivity conservation to recognize human aspirations and connectedness to land, social values and management institutions. It is about how people feel and value natural, interconnected landscapes. It is about the active involvement of people and organizations in connectivity conservation management: that is, action to conserve landscape, habitat, and ecological and evolutionary connectivity. In a dynamic world of climate change it includes conserving large natural lands that interconnect and often embed (surround) protected areas and help to maintain opportunities for species survival for the long term. Action may also seek to conserve ecologically important linkages across natural and semi-natural lands that are separated by development. Connectivity conservation helps maintain opportunities for species to maintain genetic diversity and resilience and to move, adapt and respond to climate change and to other global change pressures.

The landscape over which connectivity conservation action is being undertaken has been described by this book as a ‘connectivity conservation area’. It may include all or some of the features that contribute to landscape connectivity (wildlife corridors, stepping stones and other features). We are using this generic term given there are many different descriptions for landscapes where connectivity conservation is taking place. They have been described (for example) as biolinks, linkages, ecological networks, ecological corridors and connectivity corridors, among many other terms. To assist readers, we define some of these terms (see Chapter 2 and the Glossary), but for reasons of clarity and simplicity we have used the generic term ‘connectivity conservation area’ (which we may abbreviate to ‘connectivity area’) in this book. A connectivity conservation area is essentially any natural or semi-natural lands that includes, interconnects and embeds protected areas and where connectivity conservation is a primary objective. In nearly all instances, it is a generic term for lands managed for connectivity conservation.

A connectivity conservation area needs active management and we use the term ‘connectivity conservation management’ to indicate this. It includes a process of formally recognized management, and recognizes key management functions such as ‘planning’ that are needed to achieve conservation outcomes. Connectivity management is guided by a vision and the purpose of management is to achieve conservation of biodiversity. How connectivity conservation is undertaken and what tasks are important provides a focus for this book.

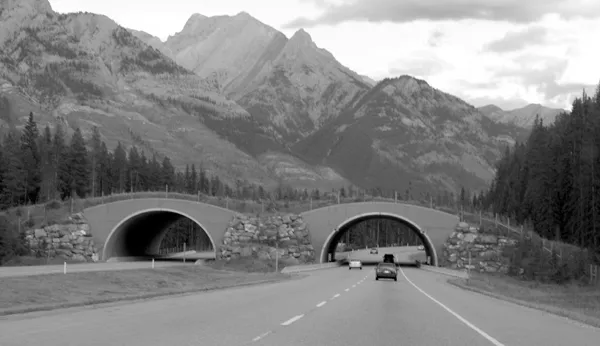

A Trans-Canada Highway ‘wildlife crossing’, one of many structures that successfully provide Yellowstone to Yukon connectivity conservation across an otherwise dangerous barrier for wildlife

Source: Graeme L. Worboys

The book takes a strategic approach to connectivity conservation and emphasizes ‘large-scale’ connectivity conservation areas and their management. This reflects a plan by IUCN WCPA to facilitate the retention of large, natural interconnected lands on Earth (particularly in mountain areas) to help conserve species and the associated archipelago of protected areas for the long term (IUCN WCPA, 2008). These are areas that are tens of kilometres wide (or wider) and hundreds if not thousands of kilometres long.

Ideally, such connectivity conservation areas will have been carefully selected for their strategic conservation benefits and the cost-effectiveness of their management. Their size typically means that they include many protected areas embedded within them and they include, outside of protected area boundaries, many important habitats and functioning ecosystems. The large size should provide effective connectivity for species between protected areas. By focusing on large-scale areas, we have also tried to avoid some of the questionable conservation benefits of smaller wildlife corridors (Chapter 2). Bennett (2003) comments on large-scale connectivity conservation areas:

Linkages [connectivity conservation areas] that maintain the integrity of ecological processes and continuity of biological communities at the biogeographic or regional scale have a more significant role than those operating at local levels. Effective linkages at these scales have a key role in the maintenance of biodiversity at the national level, or at the international level where linkages cross borders between several countries.

Given that connectivity areas are recognized as being essential to the maintenance of biodiversity, what types of land and land uses are reasonably compatible with connectivity conservation? There are a number of land-use types that may be compatible with nature conservation, provided they are managed with that goal in mind. These are in addition to IUCN Category I-VI protected area lands, world heritage areas, Ramsar wetlands and biosphere reserves that may form the core of connectivity conservation areas. Land tenures include community owned, indigenous, leasehold, Crown or public and private lands. Relative to this ownership, there are also a range of land-use types that need to be considered (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Non-protected area lands that may support connectivity conservation

Landownership and land uses that may support connectivity conservation | Notes |

Private lands | Natural private lands purchased or managed by philanthropic organizations or private individuals for the purpose of nature conservation |

Private lands (restored) | Private landowner restoration of forests and native vegetation on previously cleared lands – the restoration may be sponsored by government grants |

Private lands (stewardship) | Lands that benefit from government policies promoting connectivity conservation areas (biolinks or corridors) in the landscape |

Private and community lands (NGO stewardship) | Private and other lands (such as community lands) that are subject to NGO stewardship and incentive schemes for restoration and conservation – this may include land purchase and the creation of a conservation covenant over the land title |

Private lands (offset schemes) | Conservation values offset through covenants in perpetuity in strategic locations (such as connectivity conservation areas) – for example, the New South Wales Government’s biobanking scheme where farmers commit to enhance and protect biodiversity values on their land (DECC, 2009) |

Private lands (carbon sequestration) | Private or other lands that are reforested for commercial gain though carbon credit trading schemes |

Private lands (ecotourism initiatives) | Private lands where natural vegetation is retained and restoration work is undertaken as part of an ecotourism destination |

Private and public lands (water catchment) | Catchment areas that are conserved under regulation, certification or policy for hydroelectric power, drinking water and irrigation – in some cases owners earn a return for providing water, as in the Condor Biosphere Reserve, Ecuador, for example (Echavarria and Arroyo, 2004) |

Private lands (catchment stability) | Lands that are conserved to protect catchments from soil erosion and from slope instability, especially in extreme storm events |

Private lands (hunting reserve) | Areas that legally protect wildlife for trophy hunting (such as in the Swiss Jura Mountains) |

Private lands (recreation park) | Legally protected areas for recreation and wildlife (such as the Dyrehaven Park in Copenhagen) |

Private lands (breeding sites) | Areas under voluntary agreements to protect bird breeding sites |

Private lands (natural grazing) | Commercial properties that use native animal stock (such as the North American bison (Bison bison)) and native grasslands for their business (such as Ted Turner’s ranch in Montana) |

Public lands (forest reserves) | Legally conserved lands either within a designated forest or include an entire forest area under a mechanism not recognized as an IUCN category protected area |

Public lands (production forests) | Production forests where codes of practice, rotation cycles, third party certification or other sustainable use forestry management practices provide real opportunities for long-term connectivity conservation areas |

Public lands (avalanche control) | Areas legally protected to help protect communities and people from avalanches |

Public lands (wildlife corridors) | Lands designated by local or provincial/state authorities as wildlife corridors, such as those established by the Town of Canmore, Alberta, Canada |

Community lands (sacred sites) | Sites conserved by voluntary agreement, which may be very location specific or include an entire feature such as a mountain or mountain range (Bernbaum, 1997) |

Public lands (cultural sites) | Legally conserved sites, such as Angkor Wat in Cambodia, which protect cultural features and sites as well as biodiversity |

Source: Adapted from Dudley and Parish, 2005, p76

Other types of land uses on public or private lands may also be compatible with connectivity conservation under the appropriate conditions. For example, carefully managed grazing by domestic livestock may sustain grassland ecosystems. Innovative best practices in industrial sectors, such as hand-cut seismic lines used in oil and gas exploration, may also maintain the intactness of the landscape.

Connectivity conservation areas are not a substitute for protected areas. The highest priority for nations should be to finalize their reserve systems consistent with the Secretariat for the Convention on Biological Diversity plan of action for protected areas (Dudley et al, 2005). However, it will not be possible to achieve reserve establishment for all natural lands and this is why connectivity areas are an important next conservation initiative for nations. Connectivity areas will include important habitats and provide opportunities for species to move. A large-scale interconnected landscape of natural lands with embedded protected areas provides opportunities for many species to respond to the forecast effects of climate change and other human pressures. Connectivity areas are an integral part of a biodiversity conservation strategy for a nation.

It should be noted that some large remaining intact wild (natural) areas left on Earth such as the Boreal Forests of Canada, the rainforests of the Amazon and other wild lands or wilderness areas are not in themselves connectivity conservation areas. These are very large, undisturbed natural areas that are exceptionally valuable for their functioning ecosystems and the absence of human pressures, and they need to be managed to retain their wildness and wilderness values. However, while such areas are not connectivity ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures, Tables and Boxes

- Acknowledgements

- Preface by Nikita Lopoukhine

- Foreword by Gary Tabor

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Glossary

- Part I: Setting the Context

- Part II: Applied Connectivity Conservation Management: Case Material

- Part III: Synthesis

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Connectivity Conservation Management by Graeme L. Worboys,Wendy L. Francis,Michael Lockwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias biológicas & Ecología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.