1.1 Introduction

On a scale the world has never seen before, China’s urban expansion and real estate development have recently been widely observed, reported and commented on. New buildings of all types have been emerging relentlessly in Chinese cities and towns. The urban landscape of Chinese cities features glittering skyscrapers, lofty residential tower blocks and grandiose shopping centres in the urban area (for example, see Figure 1.1) and countless commodity housing estates, retail outlets and industrial parks spreading out to the suburbs. The real estate market has been overheating and overshadowing the country’s stock market and any other market, with frequent scenes of overnight queuing at the sales offices of commodity housing estates under construction. In 2013, over 10 million new commodity housing units were sold, consolidating the position of the Chinese housing market as the largest in the world. Acting as a growth engine, the real estate market has generated funds for Chinese cities to build state-of-the-art infrastructure: high-quality road networks, mass transit railways, ports and airports. Today Chinese cities are playing a crucial role in propelling the Chinese economy to become the largest in the world in the near future. The rest of the world stands to benefit from this urban miracle by supplying raw materials, machinery, luxury goods and money to the booming Chinese cities, and gaining from value-for-money manufactured goods, spendthrift tourists and, increasingly, money for investment. The Chinese real estate market is therefore important to the economic fortune of not only China but also of the rest of the world.

On the other hand, sceptics and pessimists have questioned the sustainability of China’s urban growth, predicting ‘crashes’ or even a ‘meltdown’ of the real estate market and the subsequent ‘collapse’ of the Chinese economy. There is plenty of ammunition for such doomsday talk: mass protests against forced demolition and relocation, congestion, pollution, unaffordable high prices, ‘ghost towns’, and high local government debts linked to massive urban expansion. To the cynics, the slowing down or even hard landing of the real estate market will weaken urban economies, which in turn will act as a drag on the country’s economy. The collapse of the real estate market, according to them, will end the country’s three-decade-strong economic growth. Indeed, Chinese GDP growth has slowed to 7.7 per cent in 2013 from 14.2 per cent in 2007 (see Chapter 2). Further slowdown, cynics say, will lead to mass unemployment and the eventual ‘collapse’ of the Chinese economy. What is not made explicit, however, is the impact that a Chinese slowdown or collapse would have on the world economy.

FIGURE 1.1 Shennan Road East, Shenzhen

At the time of writing in the middle of 2014, it is clear that the Chinese real estate market has suffered a severe structural imbalance that needs to be addressed. The future of the Chinese real estate market is now a serious concern for businesses and governments in China and beyond. This book provides an in-depth understanding of how the Chinese real estate market has developed and gained such an important role in the Chinese economy and now is generating some serious structural problems. The reader will be able to understand how the regulators and market players interact to sustain the real estate market’s contribution and why investment opportunities have abounded during the transformation. To set the scene, a brief history of the Chinese real estate sector is provided in Section 1.2.

1.2 Real estate in China: sixty years, three worlds

Real estate is important to the functioning of an economy and to the living standards in a society. It is a factor of production and in a mature market economy, a major category of investment assets held by individuals, families, companies and financial institutions. It is upon these assets that lending, pensions and social benefits depend.

For more than a century, the provision of real estate in China has fluctuated under drastically changing politico-social conditions that had strong implications for economic growth and living standards. During this period, three vastly different systems of real estate provision, referred to as three worlds in this book, were created under vastly different sets of political, economic and social conditions. These sets of conditions symbolise the three distinct periods in China’s modern history: (1) the feudal and semi-colonial Qing Dynasty until 1911 and the turbulent Republic of China from 1911 to 1949; (2) the Communist People’s Republic of China from 1949 to 1978; and (3) the reformist People’s Republic of China from 1979.

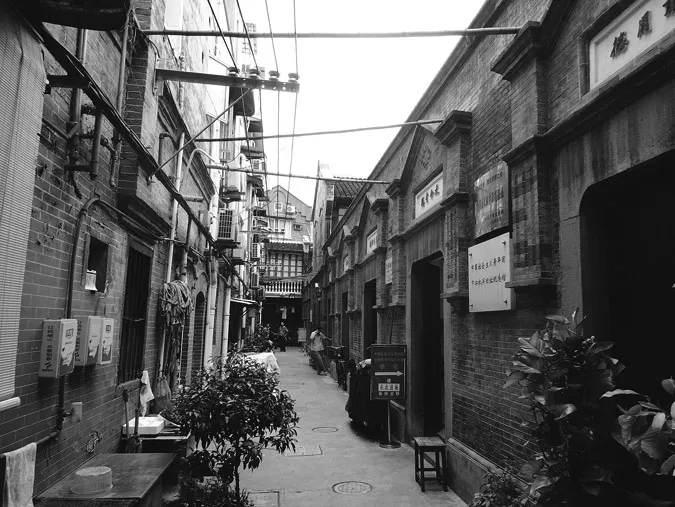

The first world is characterised by real estate poverty under domestic unrest, foreign invasion and weak governance in the first half of the twentieth century. Housing shortages in major cities, particularly in the treaty ports,1 was acute during late Qing Dynasty (from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century) and was exacerbated by uncontrolled migration, uncoordinated construction, war destruction and slow rebuilding during and after the Japanese invasion (1931–45) and the civil war (1946–49). For instance, a net reduction of 10,177 residential buildings, mostly in multiple occupation, in Wuhan City, a major industrial and commercial city in central China, was revealed by building surveys conducted in 1936 and 1952. In the meantime, the urban population in Wuhan City increased from 0.9 to 1.3 million (Zhang, 2009). Due to lack of or delayed maintenance, most of the half-timbered buildings in the city were in a poor condition by 1950. A housing condition survey conducted in the city in August 1952, covering 633 buildings, concluded that 214 required minor repair, 235 needed major repair and 25 were beyond repair (ibid.). In Shanghai, the most developed and dynamic city in China, permanent housing was built to replace temporary housing in vast numbers in the first 30 years of the twentieth century (Figure 1.2). However, redevelopment of the very poorly constructed shanty houses and sheds resulted in riots by the residents in 1925. As a result, the spread of slum housing continued. By 1949, per capita living space was 3.9 m2 (for the internal floor area, excluding the kitchen, the toilet and shower) in Shanghai, with 13.68 per cent of housing being shanty houses and sheds (Shanghai Chorogophy, 2014).

FIGURE 1.2 Yuyangli, Huaihai Road, Shanghai, an old housing estate built in 1917

The establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 drastically changed the conditions for real estate provision and threw the country into a different world. Nevertheless, this different world still featured housing poverty and dilapidated commercial real estate but under completely different conditions: severely limited resources, inefficient public provision, and a controlled but still rapidly increasing urban population. Real estate in urban areas in Mainland China2 was gradually nationalised as the country adopted a Soviet-style command economy and urban housing accommodation was considered the responsibility of the state. The real estate industry and the real estate market disappeared in Shanghai after 1956 (Zhang, 2012). Facing trade blockades and military tension,3 first from the West, led by the United States, and later from the Soviet Union, the Chinese Government prioritised industrial projects in order to develop the small laggard industrial sector that it had inherited from its pre-1949 predecessors, at the expense of housing and non-industrial real estate (Wu et al., 2007; see Chapter 2 for more details). During this period, China’s urban real estate was provided mainly by the public sector through administrative rather than market allocation, with market trading of real estate being illegal. By charging very low rents, urban housing providers could not sustain housing provision. Urban housing was regarded as a drain on the resources that were desperately needed for more productive activities. The Cultural Revolution that disrupted economic growth seriously reduced housing construction from 1966 to 1976.

Because of limited resources being made available for housing and with rapid urban population growth (from 57.7 million in 1949 to 172.5 million in 1978) (NBSC, 2013), major improvements in housing standards were prevented, with urban housing conditions being poor throughout this period. By 1978, the national average per capita housing space in urban areas was 3.6 m2 (Zhang, 1998), and most housing units were not self-contained. There was very limited availability of retail and leisure real estate. Because land was allocated without charge, wasteful use of land was widespread, with many industrial projects occupying far too much land in central urban locations.

Compared to the abrupt change from the first to the second world, the transition to yet another new world of real estate has been more gradual. In December 1978, the ruling Communist Party decided to carry out reforms to China’s rigid and inefficient command economy to promote productivity, and to open up the country to international trade and other exchanges to take advantage of the gradual lifting of the blockade by the West after the visit of US President Richard Nixon to Beijing in 1972. The importance of real estate as a factor of production and as a company asset was soon recognised when China used land as its input into Sino-foreign joint ventures with overseas investors after 1979. The real estate market, once illegal and, in theory, non-existent under the command economy, re-emerged when real estate transactions were permitted between state-owned firms, foreign firms4 and individuals in the early 1980s, initially in the Pearl River Delta, adjacent to Hong Kong, and in Shanghai. In 1987, open market land sales were conducted in Shenzhen, a ‘Special Economic Zone’ set up to experiment with economic reforms and opening-up measures.5 This led to an amendment to the Constitution in 1988 to allow market transactions of state-owned urban land. It was expected that market allocation of land and buildings would improve the efficiency of land use and would generate more economic activities as firms and individuals sought to benefit from the provision and use of real estate.

The creation of private property rights on real estate started with the resumption of ownership rights over buildings in the 1980s. In 1990, a new land tenure system was established to allow private and foreign ownership of leasehold interests (Land Use Rights, or LURs) on state-owned land. Housing reforms, which changed urban housing from being a form of welfare from the state to a type of commodity, began in 1980 to relieve the state of the burden of housing provision and to promote the market as the main provider of housing. From the 1990s, the housing reforms became, in essence, a campaign to privatise the country’s state-owned housing. Compared to the high-profile and dramatic changes in the former Eastern Bloc in the 1990s, the land use reform and housing reforms in China are ‘quiet’ property rights revolutions (see Section 2.1 for more details).

Since the 1990s, the role of the real estate market in economic growth and urbanisation has been widely recognised by both central and local governments in China. In 1998, the final phase of the housing reforms was rushed through, i.e. full privatisation to boost demand for commodity housing to help the economy fight spillovers from the 1997 Asian financial crisis. The reforms succeeded and the housing market took off. In 2003, the real estate sector was awarded the status of a pillar industry (key industry) to buttress rapid economic growth. With favourable policies and local government support, the real estate industry has become a key driver of economic growth, as indicated by its share of the national economy. China’s nominal GDP in 2013 was 46.17 times its 1987 size while investment in market-oriented real estate development was 573.42 times greater. The share of GDP by real estate and construction industries rose from 2.19 per cent and 3.18 per cent respectively in 1978 to 5.62 per cent and 6.87 per cent in 2012 (NBSC, 2013).

Growing with the Chinese economy after the reforms and the opening-up campaign, this new world of real estate has finally ended the era of chronic real estate shortage due to abundant resource inputs, market provision and supportive policies. It has provided space for living, leisure and work to accommodate the largest urbanisation the world has ever seen. China’s urbanisation ratio, expressed as the proportion of urban population to total population, grew from 10.64 per cent in 1949 to 17.92 per cent in 1978 and to 53.73 per cent in 2013 (Table 1.1), with the majority of the population living in urban areas since 2011. Housing production has expanded phenomenally, with total urban housing completion rising from 203.4 million m2 (gross external area, GEA) in 1987 to 1,073.4 million m2 in 2012. The housing market has dominated urban housing provision. In 2012, commodity housing as a proportion of total housing completions rose from 11.7 per cent in 1987 to 73.6 per cent. Per capita housing space in urban areas, a measure of housing standards, rose from 6.7 m2 GEA in 19786 to 32.9 m2 in 2012 (NBSC, 2013). Finally, this third world of real estate provision has created a dichotomy between homeowners and non-homeowners with implications for the country’s politics, economy, society and environment. The former are increasingly wealthy as commodity housing prices have grown quickly, while the latter are increasingly falling behind in wealth.

In the past 60 years or so, China’s real estate sector has changed from one form of poverty to another, and then to a world of relative plenty. This book is devoted to explaining how this world of plenty came about and what is likely to happen in the future.