- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Life-span Perspectives and Social Psychology

About this book

First published in 1987. There is a wide gap between life-span research and mainstream social psychology, and this book strikes a bright spark between these poles. promising as a corrective to narrowness and sterility. The chapters reflect a wide variety of approaches in social psychology, as well as considerable breadth in the range of ideas from life-span human development that are brought to bear.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Life-span Perspectives and Social Psychology by R. P. Abeles in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

—1—

IMPLICATIONS OF THE LIFE-SPAN APPROACH FOR RESEARCH ON ATTITUDES AND SOCIAL COGNITION

University of California, Los Angeles

Every science has its own methodological idiosyncracies. Pharmacological research relies heavily on the white rat; research on new birth control techniques is most commonly conducted on non-American women, astronomers use telescopes, and psychoanalysts depend on self-reports of affluent self-confessed neurotics. Ordinarily, such researchers trust that they have a reasonably good grasp of the biases introduced by their own particular methodological proclivities and can correct their conclusions for whatever biases are present. But conclusions can be so corrected only if the direction and magnitude of bias can be estimated on the basis of reliable empirical evidence. Such systematic evidence may not always exist, or it may be hard to come by, or it may not even be sought after. The danger then is that biases due to overreliance on a particular methodology may be ignored and the conclusions of the science may themselves be flawed.

This chapter suggests that social psychology has risked such biases over the past 25 years by its increasingly heavy dependence on a very narrow data base: college student subjects tested in the academic laboratory. The goal of scientific social psychology is to verify causal propositions that will contribute to a general theory of social behavior. But as far as most people are concerned, the proof of this particular pudding will come in the development of a portrait of human nature that will accurately account for the social behavior of ordinary people in “real-life” situations. My concern is that overuse of this one narrow data base may have biased our field’s substantive propositions, unwittingly leading us to generate a portrait of human nature that describes rather accurately the behavior of American college students in an academic context but that distorts the nature of human social behavior in general.

The chapter begins by documenting the growth of social psychology’s heavy reliance on this narrow data base. It then proceeds to a description of the biases such reliance may have introduced into the central substantive conclusions of the field. These biases could in theory be assessed in two ways. One is through systematic replication of empirical findings with other populations and situations. In practice, however, these data do not now exist, so this is not a practical approach. The second involves estimating these biases from the known differences between our data base and the general population in everyday life, and the known effects of those differences.

That is my approach, drawing upon research conducted from a life-span perspective, and using as examples several of the most important topics in the subfields of attitudes and social cognition. But it is frankly speculative. As a result I would not expect this chapter by itself to instigate wholesale abandonment of our familiar, captive, and largely friendly data base. I would hope, however, that it might generate some serious thought about how this narrow data base has affected our major substantive conclusions. I doubt that they are completely wrong. But taken together as a cumulative body of knowledge presented by the field of social psychology, they may give quite a distorted portrait of the human beast.

A NARROW METHODOLOGICAL BASE

The first great burst of empirical research in social psychology was in the years surrounding World War II. It utilized a wide variety of subject populations and research sites. Cantril (1940) and Lazarsfeld, Berelson, and Gaudet (1948) investigated radio listeners and voters; Hovland, Lumsdaine, and Sheffield (1949), Merton and Kitt (1950), Shils and Janowitz (1948), and Stouffer et al. (1949), studied soldiers in training and combat, whereas Lewin (1947) and Cartwright (1949) looked at the civilian end of the war effort, and Bettelheim and Janowitz (1950) at returning veterans; Deutsch and Collins (1951) and Festinger, Schachter, and Back (1950) investigated residents of housing projects; and Coch and French (1948) studied industrial workers in factories. Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, and Sanford (1950) investigated authoritarianism in a wide range of subjects, from college students to merchant marine officers, veterans, and members of unions, the PTA, and the League of Women Voters. Even Leon Festinger, in some ways the godfather of laboratory-based experimental social psychology, based his best-known book, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957), on data bases ranging from the analysis of rumors in India and the participant-observation of a millenial group to carefully crafted laboratory experiments on college students. The conventional methodological wisdom of the era was that the researcher must travel back and forth between field and laboratory in order to bracket properly any sociopsychological phenomenon.

The subsequent generation of social psychologists created the experimental revolution. They were much more thoroughly committed to the laboratory experiment and inevitably equally thoroughly to the use of undergraduate college students (the well-known “college sophomore”) as research subjects. By the 1960s, this conjunction of college student subject, laboratory site, and experimental method, usually mixed with some deception, had become the dominant methodology in social psychology, as documented in several systematic content analyses of journal articles (Christie, 1965; Fried, Gumpper, and Allen, 1973; Higbee & Wells, 1972).

Almost as soon as this experimental revolution achieved predominance, however, it came under attack from several quarters. Most notably, there was concern about its possible biases, such as demand characteristics, experimenter bias, and evaluation apprehension. Hovland (1959) went one step further and began to assess systematically the influence of methodology on the substantive conclusions of attitude change research. Others demanded more “relevant” and applied research that would directly address problems of racism, gender, politics, education, health, law, and other “real-world” concerns. These developments could potentially have returned social psychologists to broader methodological practice.

However, the 1970s also witnessed the rapid development of research on attribution and social cognition. Much of it was directly modeled on work in cognitive psychology, employing brief, emotionally neutral laboratory experiments on college students. Paper-and-pencil role-playing studies became especially common. As a result, social psychologists would seem to have maintained their dependence on laboratory studies of college student subjects as their primary data base.

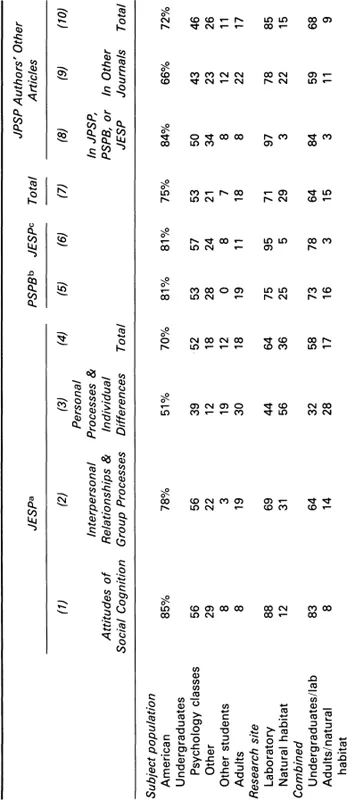

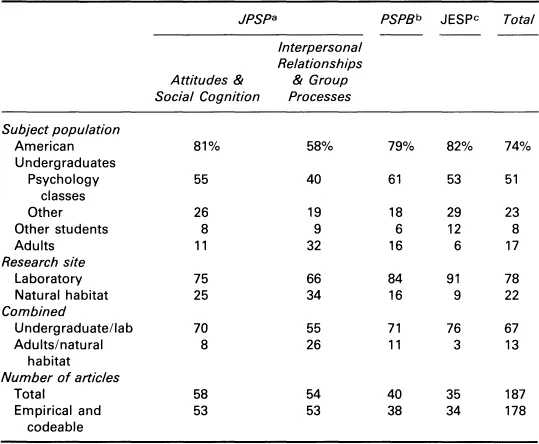

This account of the changing methodological bases of social psychology is simply impressionistic. Although most might find it fairly plausible, it is no substitute for a systematic inventory of actual methodological practice. Hence we coded a sample of recently published articles in social psychology for subject population and research site. The articles coded were all those published during 1980 and 1985 in the three mainstream outlets for sociopsychological research, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (henceforth JPSP), Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin (PSPB), and the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology (JESP). Subject populations were coded into four categories: (1) recruited directly from a North American undergraduate psychology class; (2) other North American undergraduates; (3) other students (mainly primary and secondary school students, or college students in other westernized societies); or (4) adults. The site of the research was coded as either (1) laboratory or (2) natural habitat. The latter was interpreted quite liberally, to include either a physical site in the individual’s ordinary life (such as college gymnasiums and dormitories, beaches, military barracks, a voter’s living room or airport waiting rooms), or even self-report questionnaires about the individual’s daily life and activities (concerning, for example, his or her personality, political and social attitudes, or ongoing interpersonal relationships), no matter where they were administered.1

TABLE 1.1

Subject Population and Research Site in Social Psychologists’ 1980 Journal Articles

Subject Population and Research Site in Social Psychologists’ 1980 Journal Articles

Note: The base for all percentages includes only articles shown in the last row (empirical, codeable, and available in the library). Columns 4 and 5–7 include all such 1980 journal articles; columns 1–3 include all such journal articles for April through December 1980, the first nine months of the tripartite division of the journal; and columns 8–10 are based on all such articles obtained from entries given in the 1980 Psychological Abstracts. Some articles could not be located (8%), others could not be coded (3%), and still others were non-empirical articles (15%). The percentages presented exclude all these from the base.

a Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

b Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

c Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

American college undergraduates were overwhelmingly the subject population of choice. In 1980, 75% of the articles in these journals relied solely on undergraduate subjects, almost all from the United States. Most (53%) stated they used students recruited directly from undergraduate psychology classes, but this is probably an underestimate, because many studies relying on undergraduates do not specify their origin further. All total, 82% used students of one kind or another. By far the majority (71%) were based on laboratory research. Considering these two dimensions jointly, 85% of the articles used undergraduates and/or a laboratory site; only 15% used adults in their natural habitats or dealt with content concerned with adults’ normal lives. All this is displayed in Table 1.1.

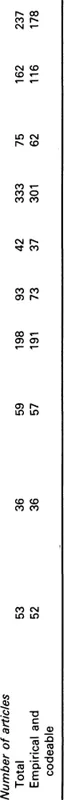

To provide more current data, these journals were again coded in 1985 (except for the personality section of JPSP, because of some dispute over its editorial policies). Table 1.2 shows that use of the undergraduate in the laboratory had diminished only marginally; 83% of the articles coded used students, 74% American undergraduates, 78% the laboratory, and 67%, undergraduates in the laboratory, and the latter remained the overwhelming database of choice. The one substantial change occurred in the Interpersonal Relations section of JPSP, which showed an increase in studies of adults in their natural habitats, from 14% to 26%. But even there, the majority (55%) still used undergraduates in the laboratory.

A Flight from Mainstream Journals?

This reliance on laboratory studies of college students might, however, only describe these mainstream journals and not social psychologists’ general research practice. Perhaps the editorial policies of these particular journals are dominated by a conformist ingroup wedded to this “traditional” (at least since 1960 or so) mode of research. Or, these journals are known to be the most selective and so might tend to reject the necessarily somewhat “softer” research that is done in “real-world” settings on less captive (and less compliant) subject populations. Or, researchers wishing to communicate with colleagues who also conduct non-mainstream research might reach them more directly through more specialized journals; for example it may be easier to reach public opinion researchers through Public Opinion Quarterly than through JPSP. It is possible therefore that social psychologists’ research published elsewhere actually use a broader range of methodologies than is apparent from inspecting these three journals.

To check this, we canvassed articles written by social psychologists that had been published in other journals. We drew a representative sample of social psychologists who had published in JPSP, consisting of the one individual listed in each 1980 JPSP article as the person to be contacted for reprints (on the grounds that he or she would be the most likely to have a research career). We then listed all the articles these social psychologists had published elsewhere in a comparable time frame—specifically, all articles listed for each such 1980 JPSP “reprint author” in the 1980 Psychological Abstracts—and coded the methodological characteristics of this new list of articles.2

TABLE 1.2

Subject Population and Research Site in Social Psychologists’ 1985 Journal Articles

Subject Population and Research Site in Social Psychologists’ 1985 Journal Articles

Note: For the base, see note to Table 1.

a Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

b Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

c Journal of Experimental Social Psychology

At first glance, these “other articles” seem to display social psychologists at work in quite a different manner, because JPSP authors also publish in a spectacular variety of other journals. The 1980 JPSP reprint authors generated no fewer than 237 other entries in that same year’s Psychological Abstracts, appearing in no fewer than 128 different journals. These ranged from such fraternal outlets as the European Journal of Social Psychology to distant relatives, arguably even of the same species, such as Behavior and Neural Biology or the Journal of Altered States of Consciousness. This variety alone might suggest that, once away from the staid scrutiny or narrow conformity pressures of their peers, social psychologists may be using strange and wonderfully different kinds of databases.

In fact, however, even in their research published in these more distant outlets, social psychologists mainly use college student subjects in laboratory settings. The last column of Table 1.1 shows that 72% of these “other articles” used North American undergraduates as subjects, actually slightly higher than the 70% that held in the original sample of the same authors’ articles in JPSP (column 4). Use of college student subjects in a laboratory setting was actually more common in these social psychologists’ “other articles” (68%) than in their original JPSP articles (58%). Viewed from the opposite perspective, only 9% of their “other articles” used adults in their natural habitat, whereas 17% of their JPSP articles had.

Perhaps this continuity of methodological practice simply reflects the fact that many of these “other articles” themselves had appeared in mainstream outlets. Indeed half of these “other articles” appeared in the basic social-personality journals (mostly in JPSP, JESP, and PSPB, with the rest scattered through 11 other journals with a similar focus). Another 21% appeared in basic psychological journals outside of the social-personality area (in experimental psychology, psychobiology, or developmental). Only 11% appeared in applied social psychology journals (on health, the environment, public opinion, women’s issues, and politics), and 17% in other applied psychology journals (including educational or clinical psychology).

What happens i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1—IMPLICATIONS OF THE LIFE-SPAN APPROACH FOR RESEARCH ON ATTITUDES AND SOCIAL COGNITION

- 2—ATTRIBUTIONS AS DYNAMIC ELEMENTS IN A LIFE-SPAN SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY

- 3—CONTEMPORARY SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY AND AGING: ISSUES OF ATTRIBUTION IN A LIFE-SPAN PERSPECTIVE

- 4—PERSONAL CONTROL THROUGH THE LIFE COURSE

- 5—THE SELF IN TEMPORAL PERSPECTIVE

- 6—SOCIAL SUPPORT AND SOCIAL NETWORKS: DETERMINANTS, EFFECTS, AND INTERACTIONS

- AUTHOR INDEX

- SUBJECT INDEX