![]()

1

Mountains and uplands: an introduction

1.0 Chapter summary

This introductory chapter provides a general overview of the different mountain regions of the world, relevant socio-economic and environmental information, and a brief insight into the causes of anthropogenic perturbations to the natural environment. The issues of global environmental change, which will be addressed in subsequent chapters, are discussed from the viewpoint of economic and demographic factors. A number of definitions are given which provide a helpful reference for the more specialized sections of the book. Table 1.1 and Box 1.1 give comparative information on socio-economic and environmental aspects of countries where mountains are a significant part of their environments. A more generic set of statistics is listed in Table 1.2 for selected countries, in order to emphasize regional differences and sensitivities to the environment and to resource use. A summary is given of the reasons why mountains are important to humankind, beyond the general perception of their marginality and geographical isolation.

1.1 Mountain Regions of the World

Mountains and uplands are often considered to comprise some of the world’s most extreme environments. However, they are of immense value to humankind as sources of food, fibre, minerals and water, and they are rich in a variety of living natural resources. Though mountains stand above their surroundings, usually more densely populated plains, they are linked to them in numerous ways, economically, socially and ecologically. Mountains are often perceived to be austere, isolated and inhospitable; in reality they are fragile regions whose welfare is closely related to that of the neighbouring lowlands.

Mountains and uplands may be defined as features of the Earth’s surface in which the terrain projects conspicuously above its surroundings, and where the slope of the land distinguishes it from the generally flat plains. While there is no universal geographical threshold above which a topographic feature may be formally defined as a mountain, certain criteria have been established in different countries. For example, in Switzerland, any surface which lies higher than 700m above sea level qualifies as a mountain zone; this particular level was chosen as a criterion for the allocation of agricultural subsidies to mountain farmers.

Mountains are different from plateaux because of their limited summit area; they may be distinguished from hills by their generally higher elevation. Mountains are normally found in groups or ranges consisting of peaks, ridges and valleys. With the exception of some isolated mountain peaks, the smallest geographical unit for an orographic feature is the range, comprising either a single complex ridge or a series of ridges. Several ranges which occur in a parallel alignment or in a chain-like cluster are known as a mountain system. Systems which are lie across significant latitude or longitude bands form a mountain chain; in some cases, an extensive complex of ranges, systems and chains is referred to as a belt, or cordillera.

Volcanism is one driving force behind mountain building; frequently associated with tectonic activity, volcanoes ideally have a characteristic conical shape composed of lava and volcanic debris, though erosion processes often transform their morphology. Examples in the world include Mt Saint Helens in the United States, Mt Etna in Sicily, Mt Irazu in Costa Rica and Mt Fujiyama in Japan. Numerous volcanoes around the globe are still active and others, while quiescent, are not extinct. Shield volcanoes are isolated systems far removed from plate boundaries, located above so-called ‘hot spots’ in the mantle underlying the lithosphere; examples of shield volcanoes include the Hawaiian Islands. On a purely local and arbitrary basis, when measured from its base on the ocean floor, Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawaii is the tallest mountain on earth (10,200 m).

Plate tectonics are, however, the principal factor for orogenesis; the compression forces associated with convergent (colliding) continental plates are capable of uplift and deformation of crustal strata. This has resulted in many of the major mountain regions of the world, in particular the Himalayas, the Andes and Rocky Mountains, and the Alps, all located in the vicinity of convergent plate boundaries. Mountain chains related to plate tectonics feature the highest summits in each continent: Mt Everest (8848 m) in the Himalayas, Aconcagua (6959 m) in the Andes, Mt Denali (6194 m) in Alaska, Mont Blanc (4807 m) in the Alps are but a few of the most famous examples. Tectonic forces operate on time scales which range from several tens of years to several hundred million years. It is important to differentiate these typical scales from those of erosion processes discussed below, which act on time scales which are between 1 and 2 orders of magnitude smaller. Hence mountains have not only a spatial component inherent to their description, but also a set of temporal scales which govern their cycle from their formation to their ultimate disappearance.

Erosion processes represent a factor other than tectonics which is responsible for orographic features. The Earth’s surface is constantly exposed to wind, ice, water, biological and chemical erosion. Rocks of varying composition resist these various erosion agents differently, so that regions of relatively hard rock may ultimately be left standing high above areas of softer, more easily eroded rock. Portions of the intermontane plateaux of the western USA, between the Rockies and the coastal ranges of the Pacific, exhibit examples of such erosion, such as Bryce Canyon in the state of Utah.

1.2 Importance of mountain regions to humankind

Mountain regions have often been perceived in the past – and to some extent still are perceived today in certain parts of the world – as hostile and economically non-viable regions. In the latter part of the twentieth century they attracted major economic investments for tourism, hydro-power and communication routes. Mountains have often been perceived as obstacles to be conquered, but their importance as a major resource for mankind is generally underestimated. Mountains in fact provide direct life support for close to 10 per cent of the world’s population, and indirectly to over half (Ives, 1992), principally because they are the source region for many of the world’s major river systems. They also sustain many important economic activities, such as mining, forestry, agriculture and energy resources.

Water resources for populated lowland regions are highly influenced by mountain climates and vegetation; snow feeds into the hydrological basins and acts as a control on the timing of water runoff in the spring and summer months. Forests delay the period of snow-melt and extend the period in which water is available for river flow; in addition, forests enhance the infiltration capacity of soils. Regions such as South and East Asia, where almost half the world’s population resides, depend largely upon water originating in the Himalaya–Karakorum–Pamir-Tibet region for economic activities such as agriculture, industry and energy production. Changes to the mountain environment, such as shifts in precipitation regimes in a changing climate, reduced snow and ice resources which today feed the major rivers flowing from the Himalayan chain, or deforestation, could significantly alter the flow patterns in rivers such as the Ganges, the Irrawady, the Salween or the Yangtze, and thereby perturb patterns of water use and water management in India, China, Bangladesh, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia and Myanmar.

Biological diversity (biodiversity) is an important issue in mountain regions. Biodiversity is high because of the fact that vegetation patterns are largely governed by climatic factors, which change rapidly with altitude. Over relatively short horizontal distances in high mountain ranges, it is possible to span a wide range of ecosystems, which would otherwise occur over widely separated latitudinal belts. For example, in tropical regions such as the Peruvian Andes, vegetation will go from tropical species at low elevations to tundra and cold-vegetation species in the upper reaches of the Cordilleras. Because of their relative isolation, mountains often harbour unique species of endemic plants and animals, such as the cloud forests in Costa Rica or Papua New Guinea and tropical montane rainforests in many of the equatorial mountain regions of the world. In the eastern Borneo state of Sabah in Malaysia, there are an estimated 4500 species of plants on Mount Kinabalu, which represents 25 per cent of the entire plant species of the United States (Stone, 1992). In terms of fauna, there are more bird species in Costa Rica (850) than in the whole of North America (Boza, 1992), including the legendary quetzal found in the mountains of Central America from southern Mexico to northern Panama. Some of our most common foodstuffs originated in mountains, such as potatoes (Andes), coffee (Ethiopia and Kenya) and wild corn (Mexico); the genetic reserves found in these regions therefore need to be preserved for future use.

Mountains provide recreational, research and educational opportunities; in terms of scenery, they are often recognized as being among the most spectacular features of our planet. Tourism is now one of the major income sources for many mountain economies; this began as early as the mid-1800s when wealthy British aristocrats began spending vacations in the mountains; mountain climbing was also at that time a key to generating interest in the Alps as a source of recreation. Many fashionable mountain resorts in the Alps, which began centuries ago as poor agricultural communities, today attract numerous tourists: Zermatt, Gstaad, Wengen and St Moritz in Switzerland; Chamonix in France; Berchtesgaden and Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Germany and Kitzbühel, Innsbruck and St Anton in Austria. The attractivity of remote mountain regions, for mountaineering, hiking or even skiing, has increased substantially over the past decade as the costs of air travel to most parts of the world have become more accessible to a larger number of people.

Mountains not only are passive elements of terrestrial environments, but also play a key role in global systems such as climate. They are one of the trigger mechanisms of cyclogenesis in mid latitudes, through their perturbations of large-scale atmospheric flow patterns. The effects of large-scale orography on the atmospheric circulation and climate in general have been the focus of numerous investigations, such as those of Bolin (1950), Kutzbach (1967), Manabe and Terpstra (1974), Smith (1979), Held (1983), Jacqmin and Lindzen (1985), Nigam et al. (1988), Broccoli and Manabe (1992) and others. One general conclusion from these comprehensive studies is that orography, in addition to thermal land–sea contrasts, is the main shaping factor of the stationary planetary waves of the winter troposphere in particular. The seasonal blocking episodes experienced in many regions of the world, with large associated anomalies in temperature and precipitation, are closely linked to the presence of mountains.

1.3 Current environmental and socio-economic information and statistics

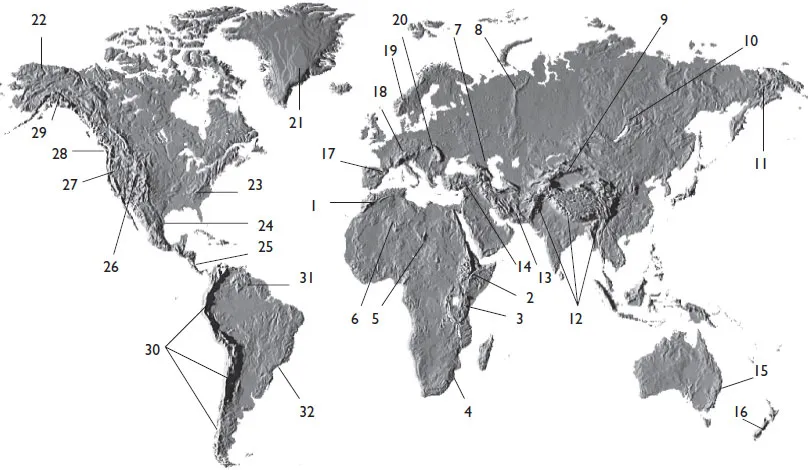

Mountains are to be found on all continents, and account for roughly 20 per cent of the world’s terrestrial surface area. Figure 1.1 illustrates their global distribution and highlights some of the more important mountain chains.

The proportion of land surface covered by mountains varies from one continent to another; the political boundaries and size of some countries imply that they may lie almost entirely within the mountain realm, such as Bhutan, while others may have no significant orography, such as Denmark. Because of the range and diversity of mountain systems, intercomparisons of environmental characteristics are not simple; in addition, socio-economic systems of particular mountain regions tend to reflect upon the general economic level in which they are embedded; the relative isolation and the harsher environmental conditions of mountains in many countries imply that economic conditions may be less favourable than the lowland regions of that country. Similar mountain regions in terms of their geographic characteristics, for example, may be totally different in terms of their societal or economic conditions.

FIGURE 1.1 Major mountain regions of the world. Numbering is clockwise for each continent. Antarctica is not shown; this continent has a number of mountain ranges, including the Vinsson Massif.

Source: Base map © by Digital Widom Inc., USA

Africa: 1. Atlas. 2. Ethiopian Highlands. 3. Kenyan, Ugandan and Tanzanian Highlands. 4. Drakensberg. 5. Tibesti. 6. Ahaggar. Asia: 7. Caucasus. 8. Urals. 9. Tien Shan. 10. Altaïr. 11. Eastern Siberian Ranges. 12. Hindu Kush–Himalaya–Pamir–Tibet. 13. Zagros. 14. Anatolian Plateau. Australasia: 15. Great Dividing Range. 16. New Zealand Alps. Europe: 17. Pyrenees. 18. Alps. 19. Scandes. 20. Carpathians. 21. Greenland Icecap. North America: 22. Brooks Range. 23. Appalachians. 24. Sierra Madre. 25. Central American Cordilleras. 26. Rocky Mountains. 27. Sierra Nevada. 28. Cascade Range. 29. Alaska Range. South America: 30. Andes. 31. Pakoraimi Mountains. 32. Sierra da Martiquera.

Table 1.1 illustrates this point by comparing extremes of socio-economic statistics for two land-locked mountain nations, namely Switzerland in the industrialized world and Bhutan in the developing world. Bhutan exhibits many characteristics typical of the developing world: relatively low life expectancy but high population growth rates, high child mortality, low literacy rates, low energy consumption and limited access to consumer goods, and a very high proportion of persons employed in the primary sector (over 90 per cent). Switzerland, as one of the most affluent countries in the world, shows almost the opposite trends in population growth, literacy and mortality rates, as well as consumer and energy-use statistics. Switzerland’s low birth rate is insufficient even to maintain its indigenous population at current levels, and the low increase in population over the past two decades is attributed solely to immigration, mostly from neighbouring countries of the European Union.

Table 1.2 provides an overview of population, economic and environmental statistics for selected countries where mountains represent a significant geographical area (IPCC, 1998); the figures in this table are intended to emphasize the points discussed in the context of Table 1.1, namely the cleavage between the industrialized world and the developing world. For several categories of data, in particular urban population, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and by sector, energy consumption per capita and the proportion of land devoted to pasture, the extremes often illustrate a ‘North–South’ disparity. North America, Europe and usually Oceania constitute the ‘North’, whereas Africa consistently represents the ‘South’. Asia can more often be grouped with Africa, whereas Latin America’s affiliation tends to vary. The division does not fall strictly around the equator, but rather around a latitude band close to 308 N. The discrepancies are also less accurately described as between industrialized and non-industrialized countries; the striking differences are seen not in the differing degrees of industrialization, but rather of ‘tertiarization’, the ‘North’ having service-dominated economies.

A high GDP per capita is associated with a major proportion of service-sector activities, high energy consumption, high urban population and a limited primary sector. It would be possible...