Introduction

It is important to trace the major events in the recent history of Europe in order to understand the development of the modern state and the changes that affect the state in the context of both European integration and contemporary trends in globalisation. The concept of state relates to questions of national identity and consciousness, and it is surely not a matter of dispute that somewhere in an analysis of the meaning of state one needs to consider these issues. Looking at the history of Europe can help us to understand the development of national consciousness, the advent of states and the notion of statehood. Later in the book we shall refer to how in some respects European integration has impacted upon these older notions, and at how globalisation in some way erodes the very consciousness and identity that has developed in European states over the past 300 years.

The Treaty of Westphalia of 1648 marked the end of the German phase of the Thirty Years War and settled a pattern of separate states that valued sovereignty and independence, as well as mutual recognition. The stability that followed the Treaty was eventually disrupted by the social and then political turmoil of the late eighteenth century, and the emergence of early forms of class consciousness. This class consciousness, combined with the intellectual force for change stemming from the Enlightenment, created the revolutionary environment that drove the ancien régime from power in the French Revolution of 1789–94.

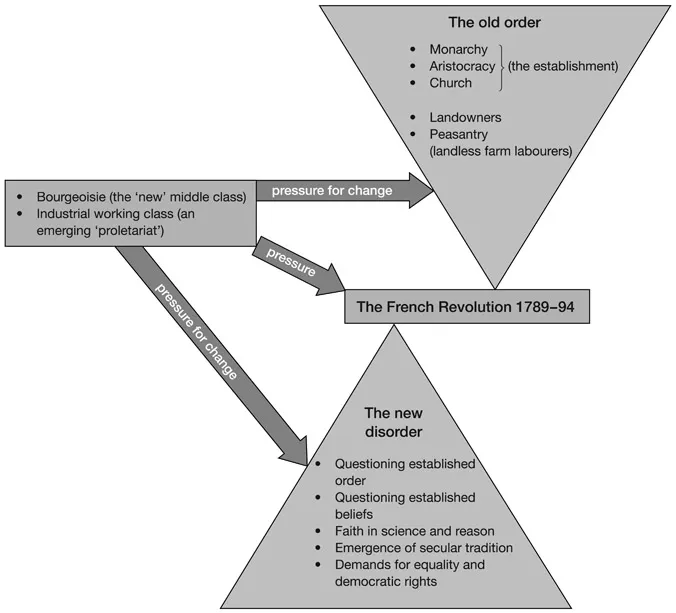

The French Revolution was a revolt against the privileges of the ruling elite comprising the monarchy, the aristocracy and the church. It was spurred by the ideals of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, especially those that questioned established beliefs, hierarchies and privileges, all of which appeared to be for the benefit of the monarchy and organised religion. The Enlightenment promoted the power of reason, affirming faith in man’s ability to resolve problems, whether technological or political. Gray (2003) describes this as a new humanism, placing humanity at the centre of all life on earth, superior to all other life forms and uniquely in control of events, a proposition he roundly dismisses as futile and at odds with the facts. Gray’s views are discussed at length in Chapters 9 and 10. Nevertheless, the Enlightenment provided a powerful and ultimately irresistible challenge to the ‘old order’. Although the middle classes had benefited from improved education and the onset of technological change in pre-revolutionary France, social conditions were deteriorating for the population as a whole, including the new urban working class. Even more significantly, the growing bourgeoisie and intellectual elite found itself isolated from the privileges of power, still zealously protected by the establishment (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The Enlightenment challenge: the pressure for change

This chapter provides the historical background to the more theoretical discussions that follow in later chapters. It begins with a discussion of the impact of the French Revolution and its contribution to the development of the state and nationalism in Europe, as well as other legacies including republicanism and secularism. The second section develops the historical background to European integration, referring mainly to the years of war and dictatorship between 1914 and 1945. The third part begins with the claim that European integration is a response to conflict. A core dimension to this conflict is not simply war, but also the experience of dictatorship, hence the inclusion of dictatorship as a key concept (1.2). If you are in any doubt as to what this term means, look at this before reading the chapter.

The rest of the final section explains the changing context within which European integration has occurred, beginning with the post-war years when the role of the United States was decisive in providing the environment in which European states could cooperate. The Cold War provided an ominous backdrop and the first fundamental change to the context of integration occurred with the ending of the Cold War in 1989–91. This coincided with the emergence of the most recent phase in globalisation, a phenomenon which has had enormous consequences for the European integration project.

The chapter presents the first two key concepts, 1.1 State and 1.2 Dictatorship.

The impact of the French Revolution

Louis XVI had begun modest social reforms, but many writers on revolutionary theory describe how attempts at reform are frequently the precursor to upheaval. Alexis de Tocqueville in his L’Ancien Régime et la Révolution Francaise (1856) claimed that many aspects of governance were improving under Louis XVI and that the king was genuinely committed to reform:

‘The social order which is destroyed by a revolution is almost always better than that which preceded it; and experience shows that the most dangerous moment for a bad government is generally that in which it sets about reform’ (the slightest acts of arbitrary power under Louis XVI seemed harder to endure) ‘than all the despotism of Louis XIV’ (de Tocqueville, cited in Davies, 1996:689).

A combination of social forces engulfed France at the end of the eighteenth century. While the rural peasantry was suffering acute food shortages and continued injustices at the hands of detached and arrogant landowners, the urban poor were increasingly hungry and jobless. The bourgeoisie were angered by their exclusion from power and by the excesses and privileges of the nobility.

The French Revolution swept the ancien régime from power and went on to have a profound impact on the development of the state in Europe. Far from ushering in a democratic system of government dedicated to liberté, fraternité et égalité, the events of 1789–94 gave rise to Napoleonic despotism and the widespread use of military force as a political weapon, and as an instrument of state policy, on a scale hitherto unknown. The response was a virtual call to arms across the continent. War fed the emergence of national consciousness and generated particularly virulent forms of nationalism. A vicious circle of nationalism, militarism and imperialism engulfed the continent.

The Revolution had already employed conscript armies and the numbers killed were testimony to the prevailing belief that armies could be used to crush political opposition. Napoleon’s conviction that he could achieve what he required through the use of huge conscripted armies pitched Europe into a protracted period of war, involving all the major continental powers as well as Britain. Conscript armies were created, although Britain had less immediate need since its naval superiority and ability to inflict defeat on Napoleon at sea meant that Britain had much less risk of suffering a land invasion. Britain did not introduce conscription until shortly before the outbreak of the First World War.

Between 1804 and 1815 the Napoleonic Wars raged, and while the Holy Roman Empire collapsed, the continuing crisis prepared the ground for Germany’s unified national identity under one flag, embracing the German–speaking peoples of Germany and Austria. Napoleon also spurred a sense of national solidarity in Britain. Free from invasion, Britain managed to enhance and develop its overseas territories, aided by a powerful navy. The British economy improved and Britain prospered, even winning control over certain French, Spanish and Dutch colonial territories. It is pertinent to point out that Britain’s perspectives in the nineteenth century always had a global orientation, a position echoed by Churchill and other British politicians in the years following the Second World War, when the emphasis once again was on Britain’s global role as head of the Commonwealth and an interlocutor between Europe and the USA. Even a casual observer of Britain’s relationship with the experiment in European integration since 1945 would conclude that old habits die hard. Britain has often seemed a ‘reluctant European’ (Gowland & Turner, 1999) or an ‘awkward partner’ (George, 1998), and some explanation for this can be found in history as far back as the French Revolution and its aftermath.

The final years of Napoleon’s leadership brought disaster to France, as between 1812 and 1814 the Russian campaign led to the conquest of Moscow, but ultimately 600,000 French troops faced starvation and were forced to retreat. Barely 1 in 20 made it back to Paris. In those two years Napoleon lost over a million men and the British, the Russians and the Prussians managed to occupy Paris. Napoleon was finally defeated by Britain, with decisive support from the Prussians, at Waterloo in 1815.

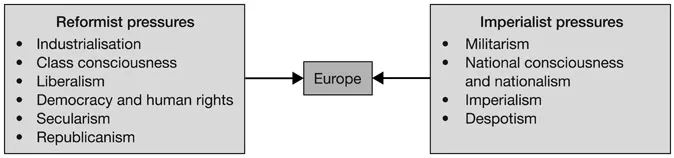

Even after 1815, a ferocious level of competition between rival powers intent on empire building continued throughout the next 100 years. The French Revolution had contributed to a sense of national identity in European countries, as well as nationalist ambition among political elites. This combination had a particularly malign effect on an unstable continent, already experiencing huge social upheavals as a consequence of industrialisation. Industrialisation had a twin impact: firstly, the wealth generated by economic progress under industrial capitalism sustained increased militarism and the imperialist adventures of the Great Powers, which in turn fostered national consciousness. Secondly, industrialisation contributed to the rapid development of political consciousness related to the emerging class system. This came to underpin the great ideological conflict of the twentieth century, capitalism versus communism. Meanwhile, drawing on the ideals of the Enlightenment and nurtured by industrialisation, liberalism became a powerful intellectual tradition. The complex and often contradictory legacies of the French Revolution are summarised in Figure 1.2.

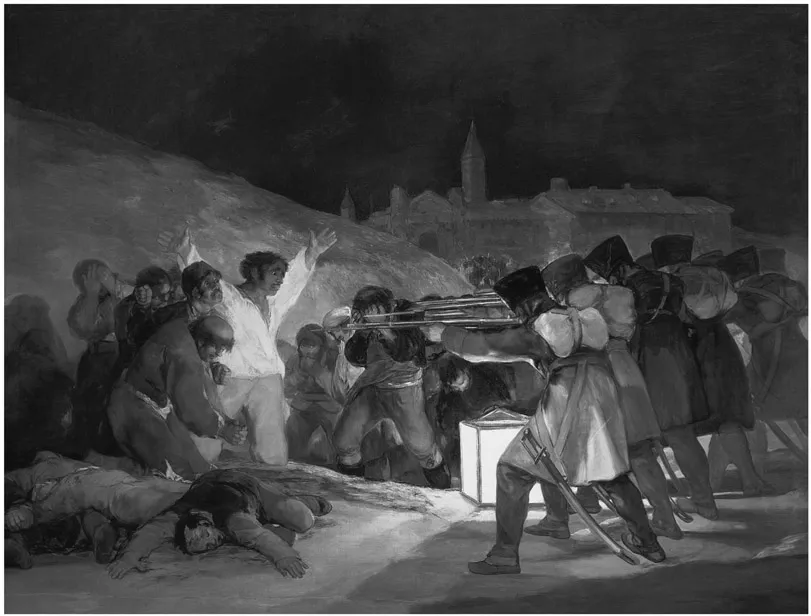

Photograph 1.1 Francisco Jose de Goya y Lucientes: The Executions on Pio Hill (3rd of May). Napoleon’s soldiers execute rebels in Madrid in 1808 … and spur nationalist sentiment in the process. Goya’s dramatic painting reflects the horrors of the French occupation of Spain, and the painter’s disillusionment with the French Revolution.

As well as a growth in national consciousness and liberalism, other important legacies such as republicanism, human rights, democratic participation and secularism would become entrenched over the following two centuries. While some of these might be considered relatively benign, others were more obviously controversial. Republicanism developed throughout nineteenth–century France for example, but never gained momentum in Britain. Nationalism, on the other hand, became arguably the most powerful influence of all, and its emergence signalled a decisive turning point in the development of modern Europe. It bolstered a sense of statehood, reinforcing the development of modern states. Italy, for example, only achieved unification in 1861 following the successful nationalist campaigns led by Garibaldi and Cavour in the south of the peninsula. Nationalism underpinned much of the conflict that scarred European history between 1789 and the end of the Second World War. Given that the growth in nationalism can be traced to these revolutionary origins, it seems reasonable to pay a brief visit to this part of European history in seeking to understand both the significance of nationalism and the role of the state in contemporary Europe.

Figure 1.2 The aftermath of the French Revolution: pressures and divisions

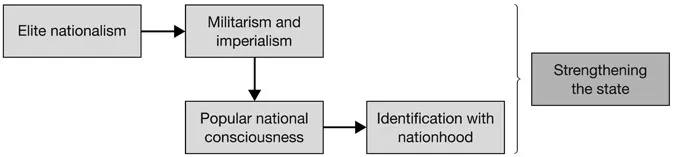

It should be apparent from this introduction that many of the legacies of the French Revolution are deeply intertwined. Militarism, a hallmark of the Napoleonic Wars, certainly contributed to competition and suspicion between states across Europe that was to have lasting impact. It also sustained and supported its common bedfellows, nationalism and imperialism, which flourished during the nineteenth century. The revolution greatly increased a sense of nationality and nationhood. As rumours swept Paris of a Prussian invasion in 1792, Robespierre asserted that the ‘fatherland is in danger’. The remark shows how the French Revolution required and achieved identification with nationhood, something which was relatively undeveloped in pre–Revolution Europe. This was by no means peculiar to France. The emergence of such identification would strengthen the idea of independent sovereign states across the continent. See Figure 1.3 below.

Figure 1.3 Developing state power in post–1789 Europe

Thus while the French Revolution boosted the concept of the state, the Revolutionary Wars of 1805–15 laid the found...