- 430 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Development of Language

About this book

This book presents a general overview of our current knowledge of language development in children. All the principal strands of language development are covered, including phonological, lexical, syntactic and pragmatic development; bilingualism; precursors to language development in infancy; and the language development of children with developmental disabilities, including children with specific language impairment. Written by leading international authorities, each chapter summarises clearly and lucidly our current state of knowledge, and carefully explains and evaluates the theories which have been proposed to account for children's development in that area.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Development of Language by Martyn Barrett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

An introduction to the nature of language and to the central themes and issues in the study of language development

University of Surrey, Guildford, UK

This book is about the development of language in children. At first glance, it may be unclear why an entire book is required to cover this topic. After all, children appear to acquire language with considerable ease, with little or no explicit teaching, and relatively few children seem to experience any noticeable difficulties in doing so. However, it is very easy to underestimate the nature of the language acquisition process, and the sheer complexity of the developmental task in which the language-learning child is engaged. In order to appreciate just how complex this task is, we first need to appreciate something about the nature of language itself.

THE NATURE OF LANGUAGE

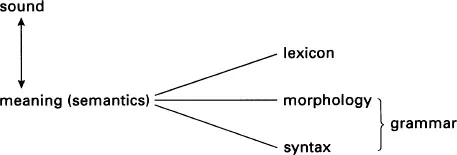

Spoken language can be characterised as a code in which spoken sound is used in order to encode meaning (Fig. 1.1).

FIG. 1.1. The nature of language (I).

The level of meaning: Some basic distinctions

To start at the level of meaning, linguists use the term semantics to refer to the study of meaning (Lyons, 1977). Meaning may be expressed not only through spoken sounds but also through pictures, conventional signs, objects, etc. (Barthes, 1967; Giraud, 1975). However, because the present book is concerned with language rather than with any of these other symbolic systems, the term “semantics” is generally used throughout this book in the more restricted sense to denote the study of the meanings which are encoded in language.

There are various components in any given sentence which contribute to the meaning of that sentence. Firstly and most obviously, the words which make up the sentence contribute to its meaning. Therefore, if a word in a sentence is changed, the meaning of the sentence changes:

1. The boys played soccer.

2. The boys played cricket.

In fact, from a semantic point of view, the word itself is not always the smallest unit of meaning in a sentence. For example, in the above sentences, the word boys actually contains two meaning units, boy and -s, where the -s contributes the meaning that more than one boy played the game. Similarly, the word played consists of two meaning units, play and -ed.

These smallest units which contribute to the meaning of the sentence are called morphemes rather than words. Some morphemes, such as boy, play, etc. can be used on their own; these are called free morphemes. Other morphemes, such as -s and -ed, cannot be used on their own; these are called bound morphemes. Sometimes, several bound morphemes can be attached simultaneously to a single free morpheme; for example, the word untimeliness contains four morphemes (cf. time, timely, untimely, untimeliness). The study of morphemes, and of how morphemes are combined with one another to form larger word structures, is called morphology (Matthews, 1974).

However, not all words that contain multiple meaning components can be decomposed into individual morphemes as simply as the above examples suggest. For example, the word ran is related to the word run, and this relationship is similar to that between played and play, but ran cannot be decomposed into two morphemes in the same way as played.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that the term “word” itself is actually ambiguous. Thus, we can say that the words found and find are two different words, but at the same time we can say that they are both different forms of the same underlying word. In order to overcome the problems which can be caused by this ambiguity of the term “word”, linguists sometimes call the underlying vocabulary items lexemes or lexical items, and they call the sound patterns word-forms (Kempson, 1977; Lyons, 1977). Notice that different word-forms can be based upon the same lexeme (as in the case of found and find), and the same word-form can be based upon different lexemes. For example, the word-forms ran in the following two sentences are based upon two different lexemes which have different meanings:

3. He ran the 100 metres in 10.9 seconds.

4. He ran the office for 17 months.

There is an enormous number of lexemes which make up any given language which the speakers of that language can draw upon in order to construct sentences. The total set of lexemes which make up any given language is called the lexicon of that language.

However, words are not the only things that contribute to the meaning of a sentence:

5. Jack kicked Jill.

6. Jill kicked Jack.

Both of these two sentences contain exactly the same morphemes, word-forms and lexemes, yet these two sentences express different meanings. This difference in meaning arises not from the meaning units themselves but from the different sequencing of these units in the two sentences. The study of the word sequences within sentences, and of the rules which govern such sequences, is called syntax.

Sometimes, the use of a particular sequence of words in a sentence requires the obligatory use of certain morphemes in order to make the sentence grammatically correct. For example, in the following two sentences, the different sequences of words require the use of different morphemes:

7. Jack is kissing Jill.

8. Jill is being kissed by Jack.

Because of this interdependence, the syntax and the morphology of a language are often studied together (Lyons, 1968). The term grammar refers to this combined enterprise, which encompasses the study of both word structures (morphology) and word sequences (syntax). Thus, grammar is the study of the rules which determine the permissible sequences of morphemes in the sentences that make up any given language. These grammatical rules dictate how the words and morphemes in that language can be combined, organised, and sequenced to produce well-formed and comprehensible sentences in order to encode particular meanings.

Consequently, our diagram summarising the nature of language can be expanded as in Fig. 1.2.

FIG. 1.2. The nature of language (II).

The level of sound: Some basic distinctions

Turning now to the other principal component of language, linguists use the term phonetics to refer to the study of the physical speech sounds which are transmitted from speaker to hearer. These physical speech sounds can be studied from two different perspectives, articulatory phonetics and acoustic phonetics.

Articulatory phonetics focuses upon the movements of the larynx, pharynx, palate, jaw, tongue and lips which the speaker uses to produce a particular sound or sequence of sounds. A fundamental distinction here is that between vowels and consonants (Gimson, 1970). Vowels are sounds which are produced when there is no blockage or partial blockage in the vocal tract and the air escapes from the mouth or nose in a relatively unimpeded way; the different vowels are produced by changing the position and shape of the tongue, the position of the soft palate, and the shape of the lips. By contrast, consonants are sounds which involve either a complete blockage of the vocal tract, or a partial blockage such that the air makes an audible sound when it passes through the partial blockage; the different consonants are produced by varying the place of the blockage in the vocal tract, the type of blockage, the position of the soft palate, by whether the vocal cords are vibrating or not, etc.

The second way of examining the physical sound wave is in terms of its acoustic properties. In acoustic phonetics, the physical properties of the acoustic signal (in terms of frequency, amplitude, intensity, and duration) are investigated (Garman, 1990). Two important discoveries which have been made here are: (1) that there is no simple one-to-one mapping between the physical properties of the acoustic signal and individual speech sounds; and (2) that breaks between words in a sentence are not signalled by breaks in the acoustic signal. For these reasons, the difficulties facing the language-learning child, in segmenting and extracting information about the units of speech from the variable and continuous acoustic signal, are considerable.

In addition to articulatory and acoustic phonetics, the sounds which are used to encode meaning in language can be examined from a third perspective which takes the phoneme as the fundamental unit of analysis. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound which functions to differentiate words from one another in a language. For example, in English, pat, pet, pit, pot, and put all vary in just one phoneme (the central vowel sound), and a change to this one phoneme changes the word into a different word which has a different meaning. Similarly, chin, din, gin, shin, and thin all vary in just one phoneme (the initial consonant sound: Note that phonemes do not correspond in a simple one-to-one fashion to the individual letters of the alphabet).

An individual phoneme may actually be articulated and encoded in the acoustic signal in a variety of ways. For example, the /p/ phoneme in the words pin, spin, and nip is articulated differently in each case, and the acoustic signal which encodes this phoneme also differs in each case. However, these articulatory and acoustic differences do not function in the English language to distinguish words from one other (thus, pronouncing the /p/ in spin in the same way as it is pronounced in pin does not change the word into another word with another meaning). Hence, these different sounds do not function as different phonemes, but as variants of the same phoneme; that is, these variations in pronunciation are functionally irrelevant.

Phonology is the study of the set of phonemes which make up any given language, and of how these phonemes may be combined, organised, and structured into syllables, morphemes, and words (Hyman, 1975). Phonology also studies how individual phonemes can change depending upon the other phonemes with which they are combined in a given word (e.g. in the English language, the phoneme /s/ in the word house becomes /z/ in the plural form houses).

Thus, whereas phonetics is the study of the full range of different sounds which are made using the human vocal apparatus, phonology is the study of just those particular categories of sound which are used in any given language in order to signal differences in meaning. Any individual language only uses a very small number of phonemes compared with the total number of different sounds which can be made. For example, the version of British English which is called Received Pronunciation contains just 24 consonant and 20 vowel phonemes (Gimson, 1970). Different languages (and different dialects of the same language) utilise different sets of phonemes. However, the total number of phonemes used in any one language represents only a minute fraction of the enormous number of different sounds which are actually produced through the vocal tract.

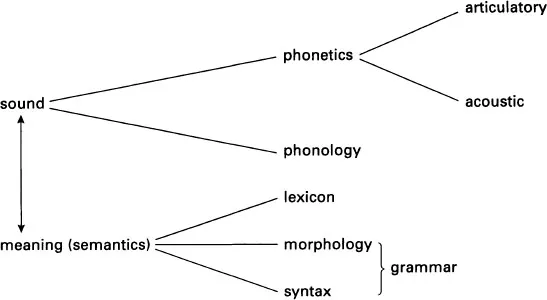

Our diagram summarising the nature of language can therefore now be expanded still further (Fig. 1.3).

FIG. 1.3. The nature of language (III).

The level of context: Some basic distinctions

So far, we have considered language at the level of meaning and at the level of sound. However, language is never used in a vacuum but always in a particular behavioural, social, or linguistic context. And this context can affect the meaning which is derived from a sentence by a listener, it can affect the choices concerning semantic content which are made by the speaker, and it can affect the lexical, grammatical, and phonetic forms which are chosen by the speaker in order to express that semantic content. The study of this complex relationship between language and the contexts in which it is used is called pragmatics (Levinson, 1983).

The fact that context can influence the meaning which is derived by a listener from a sentence is clear from the following example:

9. Can you open a window?

This sentence could be produced by someone in a hot, stuffy room, addressed to another person who is close to a window. In this context, the sentence would be interpreted as a request for the person to open the window. However, exactly the same sentence might be produced by a medical practitioner asking a series of questions about the range of everyday actions which a physically disabled person can or cannot perform. In this context, the sentence would be interpreted as an interrogative yes/no question, which requires a verbal response instead. The meaning which is derived from this sentence is thus not only dependent upon its constituent morphemes and its grammatical structure. It is also dependent upon the context in which the sentence has been produced, with the context influencing the communicative function which is attributed to the sentence by the listener.

One of the core concerns of pragmatics is the description of the different communicative functions which language can serve in different contexts, and the linguistic means by which these functions are achieved. For example, language can be used to request an action, to request information, to give information, to assert something, to make a promise, to express emotion, etc. (Searle, 1969). And depending upon the context, different linguistic means may be used to achieve a particular communicative function.

Pragmatics also examines how the features of different contexts constrain or influence the content of what we say. Context can clearly constrain our choice of semantic content. For example, one would not normally start telling jokes at a funeral, or utter obscenities in the middle of a lecture. Context can also influence our choice of lexical, grammatical, and phonetic forms. For example, depending upon whether we are in a socially relaxed, informal context (such as a party) or a more formal context (such as a job interview), the words, grammatical structures, and pronunciations which we use can vary. Our choice of language can also be affected by the nature of our relationship with the person to whom we are speaking. For example, we can ask a person to do something for us in any one of a range of different ways, depending upon our relationship with that person:

10. Close the door!

11. Close the door please.

12. Could you please close the door?

13. I’d be very grateful if you could close the door.

14. Would you mind awfully if I were to ask you to close the door?

Furthermore, in some languages the degree of intimacy between speaker and listener can have an effect upon the choice of individual word-forms (for example, the use of tu and vous in French).

A great deal of language, of course, is produced either in the context of conversational exchanges with other people, or in the context of more extended stretches of discourse in which just one person speaks for a relatively long period of time (for example, when describing an event, telling a joke, giving an explanation, etc.). Conversation and discourse both require a variety of skills. For example, conversation requires individuals to take successive turns in adopting the roles of speaker and listener, to intermesh these roles appropriately and smoothly with one another, to adapt what is said to what the other person has just said, to adapt what is said to the type of relationship which exists between the participants in the conversation, etc. Discourse requires the speaker to link successive sentences appropriately and coherently, to take the listeners’ perspective into account, to adapt the language that is used to the function of the communication, etc. Conversational analysis and discourse analysis are those sub-branches of pragmatics which are concerned with how coherence, relevance, sequential organisation, and adaptation are achieved by the speakers of a language during conversation and discourse.

Thus, our diagram summarising the nature of language finally takes on the form shown...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of contributors

- 1. An introduction to the nature of language and to the central themes and issues in the study of language development

- 2. Prelinguistic communication

- 3. Early speech perception and word learning

- 4. Phonological acquisition

- 5. Early lexical development

- 6. The world of words: Thoughts on the development of a lexicon

- 7. Early syntactic development: A Construction Grammar approach

- 8. Some aspects of innateness and complexity in grammatical acquisition

- 9. The development of conversational and discourse skills

- 10. Bilingual language development

- 11. Sign language development

- 12. Language development in atypical children

- 13. Specific language impairment

- 14. Towards a biological science of language development

- Author index

- Subject index