eBook - ePub

Alternative Conventional Defense Postures In The European Theater

Military Alternatives for Europe after the Cold War

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Alternative Conventional Defense Postures In The European Theater

Military Alternatives for Europe after the Cold War

About this book

First published in 1993. This volume, edited jointly by the American strategic expert Robert Kennedy and the German peace researcher Hans Giinter Brauch, takes up conceptual ideas developed by Horst Afheldt and Carl Friedrich von Weizsacker, as well as others on both sides of the Atlantic, since the 1960s. Our aim has been to contribute to the development of concepts that would reduce the danger of a third world war by the creation of more stable structures in the context of a defensively oriented conventional defense posture. In this volume a variety of alternative approaches to European conventional defense, driven for the most part by similar strategic considerations, are presented by German and American experts to a larger international audience.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

I

SURVEYS OF FORCE POSTURE ALTERNATIVES

1

Debate on Alternative Conventional Military Force Structure Designs for the Defense of Central Europe in the Federal Republic of Germany

Hans Günter Brauch

INTRODUCTION: DEFINITIONS OF ALTERNATIVE DEFENSE

Alternative defense is a military concept1 that has been described by many terms, such as territorial, nonoffensive, defensive, nonprovocative, nonaggressive, confidence-building, structural inability to attack, and defensive or mutual defensive superiority. These and many other terms describe a military concept that differs fundamentally from the force structures of Guderian, Fuller, and De Gaulle in World War II and those of both NATO and the former Warsaw Pact countries that have been optimized for counter-offensive or offensive operations.2 In this chapter we use “nonoffensive defense” (NOD) as the generic term for this alternative school of thinking.

Björn Möller, editor of the NOD Newsletter, defined “nonoffensive defense” in this way: “The armed forces should be seen in their totality to be capable of a credible defense, yet incapable of offense.”3 The term “nonprovocative defense” has been defined as “A military posture in which the strategic and operational concepts, the deployment, organization, armaments, communications and command, logistics and training of the armed forces are such, that they are in their totality unambiguously capable of an adequate conventional defence, but as unambiguously incapable of a border crossing attack, be it an invasion or a destructive strike at the opponents territory.”4 According to Boserup and Neild, “defensive defense” is: “. . .to ease the military confrontation in Europe by restructuring conventional forces so as to minimize the capability to attack while maintaining intact their capabilities to defend. If that can be done, it will provide unambiguous evidence of peaceful intentions; it will be mutually reassuring; and it will enhance military stability.”5 Lutz Unterseher introduced the concept of “confidence-building defense” as a reaction to NATO’s former nuclear posture and its then conventional force structure oriented at punishment rather than denial. As a defensive philosophy, it would rely on these measures:

- Removal of nuclear assets from NATO’s territory; separation of nuclear from conventional forces; and adoption of “no first use” (only if the demands on the American nuclear umbrella are greatly reduced is there a chance for some form of extended deterrence to survive).

- Creation of an inherently stable conventional deterrent, by tactically and organizationally emancipating it from nuclear weapons (which would no longer be counted upon as “trouble shooters”) giving it the capability to restrict the battle zone; making it virtually safe from being overrun, bypassed, or “outmaneuvered,” technically and tactically; and keeping it from presenting valuable targets to enemy fire, thus abolishing opportunities for the opponent making it structurally incapable of (and doctrinally not charged with) invading or bombarding the other side’s territory, thereby removing the reason for preemption.

- “Decoupling” from the arms race and consequently maintaining and improving the internal stability of the societies by doing away with the traditional concept of balance (“answering in kind”) and by specializing on defense in a cost-effective manner.6

Since the 1950s, this alternative school to the traditional military and strategic thinking in NATO and the Warsaw Pact has been a specific reaction to nuclear deterrence and conventional defense concepts, and (in the case of Germany) also to the division of Germany. This school was influenced by Carl von Clausewitz, Sir Basil Liddell Hart, Bogislav von Bonin, Guy Brossollet, and Emmil Spannocchi.7 From the mid-1970s to the early 1980s, the alternative school was primarily a German debate stimulated by the writings of Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Horst Afheldt. Subsequently the debate spread to the Netherlands (Egbert Boeker, INSTEAD); to the United Kingdom (Alternative Defence Commission, Common Security Project, Just Defence); the United States (Randall Forsberg and Paul Walker); and since 1984, via the Conventional Weapons Working Group of Pugwash, to Eastern Europe—especially to Hungary and to the Soviet Union, where it was taken up and promoted by Mikhail Gorbachev as part of the new thinking and has thus become part of the international dialogue.8 Since the 1970s, independently of Afheldt and the German debate, Stephen Canby, Ed Corcoran, and Robert Kennedy have initiated a similar debate in the United States (see Chapter 2). However, until the early 1980s, these two independent debates did not influence each other.

Most of the proposals were developed prior to unification by West German authors and a few independent thinkers in the GDR, such as Walter Romberg9 who focused on the former central front between the NATO and Warsaw Pact nations, running down the divided Germany. They were conceived of as tools to reduce the reliance on nuclear weapons; to drop NATO’s nuclear first-use option; to avoid an inadvertent nuclear attack by removing incentives for preemptive attacks; to enhance strategic and especially crisis stability; to exploit the terrain by increasing defense efficiency; to further detente and conventional disarmament; and to eliminate or drastically curtail the arms race by favoring the defense over the offense. However, the context in which these proposals were originally developed in Germany has disappeared since the winter of 1989. The question remains: Have the concepts themselves become obsolete as well.

This chapter first examines the old strategic context in central Europe, reviews the five stages of the German NOD debate, and identifies the major pure, add-on, and integrative and comprehensive proposals. It discusses the new international and domestic political context resulting from German unification and the potential implications for force restructuring.

NONOFFENSIVE DEFENSE AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO FORWARD DEFENSE?

During the 1980s, “conventionalization” and “alternative defense” were the catchwords of a debate on the military aspects of security policy in the Federal Republic of Germany. Geographic, strategic, historical, political, and economic reasons contributed to an intensive debate among government officials (the official debate), government advisers in research institutes close to or advising the Federal government (the semiofficial debate), retired officers, social scientists, and independent security experts (unofficial debate), and by peace researchers, peace activists, and the peace movement (the peace debate).10

The geographic reasons were self-evident: the territory of the Federal Republic of Germany would be the first battlefield in Europe if deterrence should fail and the East-West conflict escalate to the military level with the employment of both conventional and nuclear weapons. The strategic reasons were a reflection of the differing interpretations of NATO’s doctrine of “flexible response” and of deterrence in general in Europe and the United States, most particularly in West Germany. Since the 1950s, NATO has been confronted with a “seemingly irreconcilable conflict of interests.” Given the potential destruction of any war on their territory during the East-West conflict, Europeans, and particularly Germans, “have tended to advocate a strategy of absolute deterrence through the immediate threat of all-out nuclear war, and have looked with unease and suspicion at any development that appears to distract from this ultimate threat, or that threatens to ‘decouple’ Europe from the American strategic nuclear guarantee.”11

Americans, in looking beyond deterrence, have “emphasized the need to deter conflict at all possible levels through the provision of a wide range of capabilities and options” and, if deterrence should fail, “to facilitate the termination of any conflict short of allout nuclear war,” e.g., if a nuclear war should occur and if a conventional war should escalate to the nuclear level, to limit it and to prevent an allout nuclear war or a spillover into the continental U.S. As Americans called for flexibility and for as many steps as possible in the nuclear escalation ladder, many Europeans suspected that any increase in flexibility would lead to a strategic nightmare: the containment and limitation of any conflict to Europe. This dispute has lasted for three decades. It influenced the transatlantic multilateral force (MLF) debate in the 1960s, the intermediate-range nuclear forces (INF) controversy in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and the short-range nuclear forces (SNF) dispute in the late 1980s, as well as the debate on “conventionalization” (AirLand Battle and Follow-on Forces Attack (FOFA)) in the early 1980s.12 Whereas the MLF debate took place primarily among governments and a few experts, the INF controversy led to a broad public debate that made the West German government far more sensitive to domestic concerns during the SNF dispute. As a consequence of the peaceful revolution in Eastern Europe, of German unification, and of the agreed Soviet troop withdrawals, the political, geographical, and strategic contexts have changed fundamentally.

FIVE STAGES OF THE DEBATE ON ALTERNATIVE DEFENSE

Since its establishment in 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany was confronted with five fundamental debates on foreign and security policy:13

- In the early 1950s: on rearmament and integration into NATO and the European Community institutions vs. national unification between the Adenauer government and the Social Democratic Party (SPD).14

- In the late 1950s: on deployment of nuclear weapons or nuclear disengagement in Europe between the Adenauer government and the SPD and the first antinuclear movement.15

- In the early 1960s: on the primacy of a transatlantic (U.S.) vs. a pro-European (France) orientation within the Christian Democratic Union and the Christian Social Union (CDU/CSU) parties.

- In the early 1970s: on Brandt’s Ostpolitik, the recognition of the borders, joining the Nonproliferation Treaty and on the participation in the CSCE between the Brandt government and the CDU/CSU opposition.16

- In the early 1980s: on the deployment of Pershing II and cruise missiles and on the role of nuclear weapons in NATO strategy.17

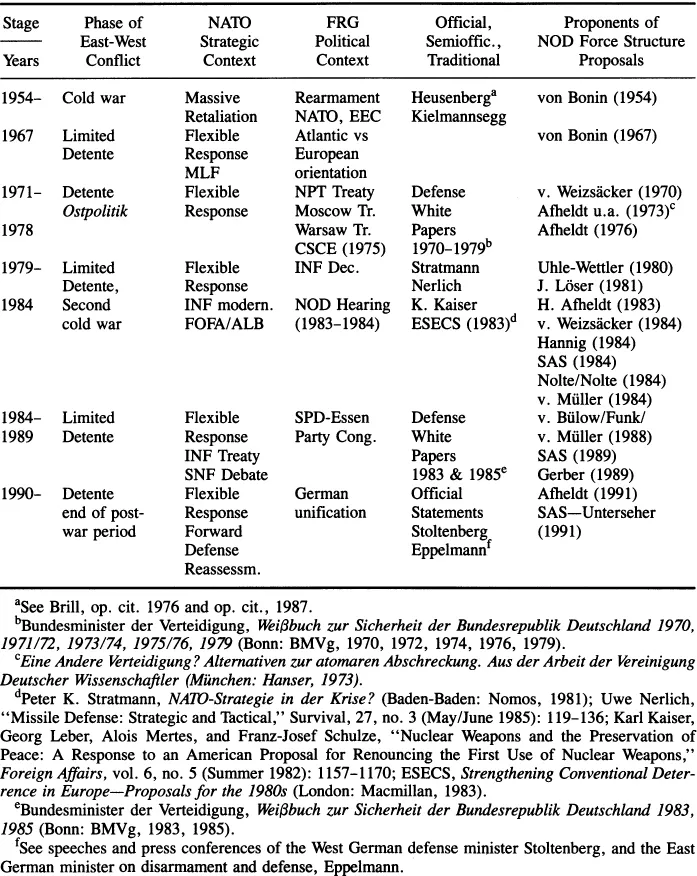

With respect to the debate on military force structures and NOD concepts, five stages may also be distinguished (see Table 1-1).

- In 1954-1955 (as the Bundeswehr was being established) among the military experts within and outside of the government.

- In the 1970s when Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Horst Afheldt published their studies on the implications and contradictions of nuclear deterrence (within the scientific community).

- In the early 1980s on the background of the public INF controversy, a search for political alternatives to nuclear deterrence stimulated the development and proliferation of NOD concepts within the scientific community and the peace movement.

- In the mid-1980s, NOD concepts for the first time had an impact on political parties, most particularly on the SPD after it lost power in 1982 and to a limited extent on the Greens.

- In the early 1990s, the first historical opportunity to include NOD concepts in the review process of military force structures and military doctrines.

Only in the context of the fourth major debate did military force posture alternatives and NOD concepts come to play a significant role. Only then were NOD proposals intensively discussed and adopted in party resolutions and into the program of the SPD.

Stage 1: Establishment of the Bundeswehr; von Bonin, an Early Dissenter (1954-1955)

The unconditional surrender of 1945, the division of Germany, and the superpower confrontation during the cold war did not provoke a fundamental reassessment of military force structures. Only Colonel Bogislav von Bonin18 dissented from the mainstream represented by General Adolf Heusinger, Count Wolf von Baudissin, and Count Johann Adolf von Kielmannsegg in the Amt Blank (later to become the Federal Ministry of Defense).

Table 1-1 Five Stages of the Debate on Force Posture Alternatives in the Federal Republic of Germany

Starting with reunification as the prevailing political objective, von Bonin designed a barrier zone along the demarcation line some 50 km wide that was to wear down and, if possible, to stop the armored thrusts of an invader. He believed that a small force of 150,000 to 200,000 soldiers could be built up within two years at relatively low cost. Von Bonin’s force structure proposal consisted of a system of small, well-camouflaged field fortifications, distributed in depth with only small armored elements for tactical counterattack, to be manned by old Wehrmacht cadres still fit for service. Most of their equipment was to consist of relatively simple, state-of-the-art weapons, e.g., about 8000 antitank guns complemented by recoilless rifles and numerous hand-laid mines. Once von Bonin made his nonprovocative concept explicit, he was removed from his position in 1953 and portrayed as a dissident.

According to the von Bonin plan, nonprovocation was to be made operational through tactics and force structure, both designed for static warfare, for denial of attrition. Large-size mechanized all-purpose forces were thought of only in the context of allied reserves, coming to chop off enemy spearheads that might eventually pierce the proposed covering army. He was convinced that the allies’ help could be counted on and that the delaying effect of the barrier zone would be welcomed by them. This purely German nonprovocative front layer was to avoid providing the Soviets with any incentive for a potential build-up of invasion forces in East Germany. No foreign mobil...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part One. Surveys of Force Posture Alternatives

- Part Two. Force Posture Alternatives

- Part Three. International and Domestic Changes: Future Roles of Germany and the United States in the New International Order

- Appendix A: Chronology of Political Change in Europe (January 1991 through October 1991)

- Appendix B: Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany

- Appendix C: Treaty Between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Republic of Poland Concerning the Confirmation of the Frontier Existing Between Them

- Appendix D: Treaty Between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on a Good Neighbor Policy, Partnership, and Cooperation

- Appendix E: Charter of Paris for a New Europe

- Index

- About the Editors and Contributors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Alternative Conventional Defense Postures In The European Theater by Hans G. Brauch,Robert F. Jr. Kennedy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.