![]()

Origin and Mission of This Book

This book builds on the work done for our former book that we edited, Digital Democracy: Issues of Theory and Practice (Sage Publications, 2000). The book addressed certain theoretical and practical issues about the use of digital media in political communication. Our 2000 book was well received and praised for its shelf life. We believe that the success of that book was due to its provision of in-depth political and communication theory in a field that is so sensitive to technological and political change. However, theoretical development and empirical research have continued since that time and many new uses of digital media in politics have emerged in the last 17 years.

What has occurred since the turn of the millennium? First of all, the diffusion of the Internet and digital media has accelerated, reaching the majority of the populations of developing countries with between 70% and 95% penetration (ITU, 2017). In this period new digital media emerged such as social media. Just like the new media before them, they were assumed to provide a number of opportunities for democracy. Simultaneously, a whole new ecology of cross-media relations of traditional and digital media emerged that is able to substantially change political communication (Chadwick, 2013; Jenkins, Ford, & Green, 2013). This new cross-media ecology used everywhere might have a bigger potential impact on democracy than the new media that emerged before the year 2000.

Second, in this period the practice of using digital media in politics and democracy has matured. This practice can be for or against democracy. The expression ‘against’ is used because digital media can also worsen the condition of democracy. For example, they help to create ‘filter bubbles’ and micro-targeting political marketing for citizens who follow the same views; to distribute ‘fake news’; to wipe away any editorial control and moderation; to harm privacy; to allow censorship; to undermine the democratic national state in globalization, and other potential effects to be discussed in this book. Less insidiously, the expansion of digital communication has empowered those who have more offline political power than those who have less. Despite noble efforts, researchers have not found any significant exceptions to this pattern. It is true that anyone can create a blog or social media post, but gaining an audience for them is another matter.

The importance of the Internet for politics has increased, and the era of broadcast and cable television political communication is gradually yielding to an era of Internet democracy or cross-media democracy combining broadcasting and interactive media. So, simply by replacing older media, the digital media create an ecology of media and offer all kinds of innovations in political communication.

In this book, we link the views and theories of democracy to concepts of communication in networks and the network society at large. This is a conceptual and theoretical mission. After the 2000 Digital Democracy book, we do not see sufficient theoretical advance in this domain. After nearly two decades of speculation and empirical analysis, it is abundantly clear that the concept of digital democracy needs a more expansive definition and theoretical underpinning. It is also clear that an explanation of networking with connection technologies requires more than empirical observations. It is important to first specify what type of democracy is under examination. To date, writing in 2017, there are no useful theories of digital media or political new media usage to explain the relation between the network society and democracy.

Of course, we do not have the pretension to offer a fully fledged theory of both democracy and digital communication. We only want to attain conceptual clarification and to offer a promising starting point for theories and empirical studies to build on in the literature.

In our Digital Democracy book we summarized three main issues for further research that serve as the most important questions for the current book (Hacker & van Dijk, 2000, pp. 220–222). First, we called for further conceptual clarification. A concept to be elaborated is the network concept. What is the relation between concepts of politics and democracy on the one hand and the conceptual distinctions of network theory on the other hand? How does increased digital communication and networking affect democracy? In these networks we also include cell phone and satellite networks, in fact all connection technologies. The answer to these questions can be aided by further clarification of concepts we addressed in our former book. The concepts of interactivity, the public sphere, public debate, community building, political participation, universal access and information or communication freedom might change in the context of myriads of new devices that are interlinking with the Internet.

A further call was to test the basic assumptions in most perspectives of digital democracy. One of the assumptions is that the new forms of communication offered by the Internet can change communication content and encourage more political communication. We were rather skeptical, but not pessimistic, about this assumption in the former book. New instruments of communication do not necessarily bring about new politics, more political motivation or more participation. “No technology is able to ‘fix’ a lack of political motivation, lack of time, effort and skills required for full participation in democratic activities” (Hacker & van Dijk, 2000, p. 210). Yet this claim is made again and again. After the year 2000, blogging was assumed to have some revolutionary impact. In the year 2004, the claim reappeared alongside the rise of participatory media in the so-called Web 2.0. Shortly afterwards, social media were adopted on a massive scale over a short period of time and are also used for political communication. Indeed, we know that after the year 2000 Internet users have become ever more active and creative, instead of just consuming website content. But does this mean that they have also become more politically engaged? The literature regarding political participation and uses of digital media continues to be marked by a conflation between correlation and causation in relation to digital media use and political engagement. In the United States, for example, digital communication has risen dramatically across all age groups while political engagement has remained fairly flat across time, as has political knowledge and faith in the government.

A final call we made in our 2000 book was for careful empirical observations to be made in evaluation research of the effects of digital democracy applications. Most often, precise goals or expected effects are not formulated in advance. The beneficial contribution of these applications to democracy is simply assumed; it is a matter of belief. With this handicap in mind, we still want to carefully balance the achievements and shortcomings of particular practices of digital democracy, comparing them with particular goals and norms.

The Claims of Digital Democracy Made in the Year 2000 and 17 Years After

Around the year 2000, fairly strong claims were made by advocates of digital democracy, as summarized by Tsagarousianou (1999):

1.Digital democracy improves political information retrieval and exchange between governments, public administrations, representatives, political and community organizations and individual citizens.

2.Digital democracy supports public debate, deliberation and community formation.

3.Digital democracy enhances participation in political decision making by citizens.

In the year 2000 we concluded that more and better information access were among the most important accomplishments of digital democracy at that time. However, we found that its value for democracy was quite another affair. Accessible, reliable and valid information is a necessary condition of democracy, but is it sufficient? We thought not. There are numerous steps between retrieving information and it having any impact on decision making. First, is the information reliable and valid or is it disinformation? Second, is the information not abundant and perceived as information overload by many people? The crucial question that follows is what one actually does with the information. Is it transformed into political action? We cited authors arguing that decisions are not necessarily improved by the simple expedience of acquiring information. Decisions are ultimately matters of judgement. The art of judgement may be hampered by an abundance of information (Hacker & van Dijk, 2000, p. 215). Since the year 2000, political information sources have multiplied. However, have the benefits in terms of political knowledge and action also grown?

A second claim made about digital democracy was its support of public debate, deliberation and community formation. In the year 2000, we concluded that the first attempts to launch debates, deliberation and communities lacked an adequate level and quality of interactivity. We observed little interactivity between contributors. Most people only read the contributions of others and did not contribute themselves. When they did, the most frequent people addressed were political representatives who did not respond or only returned automatic messages. Frequently, the debate was dominated by a few people. Finally, we observed a lack of pressure to come to a consensus or even to form conclusions as compared to face-to-face discussion groups (Hacker & van Dijk, 2000, p. 216). After the year 2000, the number of blogs, online communities and debates increased dramatically. In one decade, an important new platform used on a massive scale for the purpose of debate was born: social media. Social media platforms are used by ordinary members of the population rather than being limited to the elite that dominated online political debates in the 1990s. Have these new media of public-opinion-making facilitated public debate on a greater scale and in a better way than before?

The third claim was the enhancement of participation in political decision making by citizens using digital media. We found that there was no perceivable effect of the use of digital media on decision making by institutional politics at that time. This was in spite of the fact that a considerable amount of horizontal communication about what to do or who to vote for was initiated at that time. However, it did not have any effect on political decision making at that time. Any potential effect seemed to be blocked by the system of representative democracy (Hacker & van Dijk, 2000, pp. 216–217). It is striking that terms such as tele-democracy, tele-polls and tele-referenda that started the discussions about digital democracy in the 1980s (Arterton, 1987; Becker, 1981) have become extinct or have been exchanged with more vague terms not referring to direct democracy.

Is the claim of direct democracy by means of digital media one to be discarded? In the last 17 years, more powerful technologies for online voting and opinion making have arrived compared to the so-called cable television box remote voting (Arterton, 1987). We now have electronic voting in some countries and perhaps even proposals to use social media or more secure messaging services for reliable voting. Why are these services not offered for this purpose?

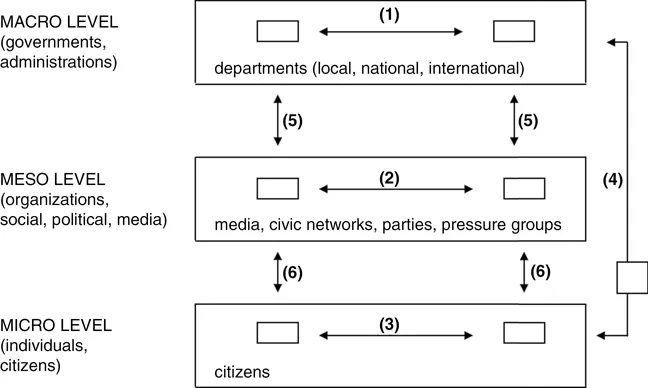

One of the reasons is that direct and representative democracy are part of separate levels of political communication that perhaps do not reach each other. In our 2000 book we presented a model of political interactivity between and inside levels of the political system (Hacker & van Dijk, 2000, p. 217). See Figure 1.1. At the macro-level we observed the exchange of government departments (arrow 1), at the meso-level party, community and pressure group communication (arrow 2) and at the micro-level communication between individual citizens (arrow 3), all levels using digital media horizontally. Next, we observed two-way vertical communication between governments and political organizations such as parties and economic organizations like businesses (arrow 5). We also saw frequent two-way vertical communication between political organizations and citizens (e-campaigning) and businesses and consumers (e-commerce), depicted in arrow 6. However, crucially direct vertical two-way communication between citizens and government was buffered (arrow 4) because governments rarely responded to individual messages from citizens. They used the mass media and their own websites to reach citizens collectively and individually surveyed citizen and voter behavior to create personal data. The other way round, some citizens tried to directly address governments but in fact had to use their representatives (the meso-level) to reach them. In this way direct democracy does not come to pass at all. Now, 17 years later, we wonder whether new platforms such as social media, e-government services and explorations of e-voting or e-referenda are able to bring more real opportunities and practices for two-way vertical communication between governments and citizens, and perhaps even change the political system.

So, in the 1990s many utopian and dystopian claims about the opportunities of digital democracy were offered. Now, 17 years later, those claims can be evaluated in the context of the growing practices of the use of digital media by governments, politicians, political parties and communities, societal organizations and civilians. These practices enable us to form a more detailed balance sheet of the performance of digital democracy than we were able to produce in Digital Democracy (2000).

It is possible to argue that the most salient contributions of digital media to politics are involvement in political activities, whether democratic or anti-democratic. The latter word, and its occurrence, could be uncomfortable for some observers because they have been conditioned to equate expanded channels of communication with increased democracy. In the 21st century, scholars should avoid ‘Arab Spring Twitter revolution’ and other deterministic statements about digital communication transforming societies or giving birth to democracies. Currently, a more cautious and data-based approach to the connections between Internet usage and political participation is needed. Actual findings tend to be more modest and less radical than the breathless praise of online technologies for democratization suggests. Data showed, for example, early in the 21st century, that both television and the Internet were prominent sources for political information and that the Internet never replaced TV as was anticipated.

Major changes in the world have occurred with movements toward both democratization and globalization. Globalization and the expansion of network societies are obviously related, but the politics of both remain unclear. China’s blend of authoritarianism with expanded networking and capitalism offers new opportunities of communication and democracy. Slowly but surely, certain forms of public opinion formation and expression are emerging among online Chinese citizens. Messaging systems such as Weibo offer this opportunity. However, while connectivity and democracy are statistically correlated, the direction of causality is unexplained. Web applications are not a magic wand to conjure up democratic systems. Although there is much excitement about closed societie...