![]()

Part One

History, Development, Identification and Dating

![]()

1

An Outline of the History and Development of the Staircase

Michael Tutton

STAIRCASES are compelling and enigmatic; in the same way that a closed door invites opening, they invite ascent or descent, to discover what awaits above or below. The conveyance to different levels of a building, the basic function of any stairs and the principal artery for the circulation and access of people, as the architectural historian Kenneth Clark observed, ‘there is always something dramatic about a staircase’,1 and almost any building greater than one storey will have one, be it of the most utilitarian type or a virtuoso work of high status and grandeur.

There are inevitably only a limited number of possible configurations for a stair, imposed by the basic materials of construction from antiquity to the nineteenth century. Thus, at any given time different architects or builders might produce similar designs without necessarily being influenced by each other. Technology plays a part. Certain types only become possible with innovations in tools or materials. Architects, engineers and builders adopt newly found or rediscovered ways of putting existing materials together. Thus the history of the staircase is not linear. Types of stairs are used but go out of fashion, they are then forgotten only to be reinvented at a later date, as is the case of the cantilevered staircase, invented by the Ancient Greeks, forgotten, then reinvented by Palladio in the sixteenth century.

From the earliest surviving examples through developments in Ancient Greece and the Roman empire; through European and Islamic Medieval worlds to the sumptuous achievements of the Renaissance and Baroque, this chapter provides an outline of the evolution of the staircase highlighting some particular types and notable examples. These are essentially stone and confined to Western civilisation, with some consideration of iron and steel types, including North America, in more recent times. Until the nineteenth century the emphasis is on spiral stairs, because these illustrate the more dramatic developments, although without excluding mention of straight flights.

Earliest Stone Stairs

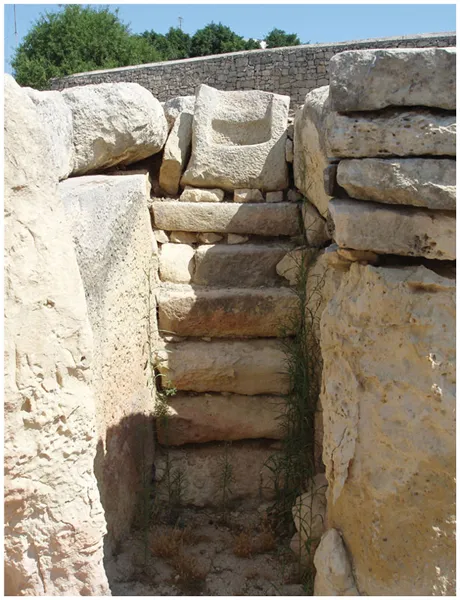

From very early times mankind has hewn blocks of stone to form stairs, mostly within religious sites. The humble and even higher status house would have made do with wooden ladders where they were needed to access areas such as lofts and sleeping platforms. Within the prehistoric Tarxien Temple and Saflieni Hypogeum site in Malta, dating to 3600–2500 BC, which lay claim to being probably the earliest free-standing megalithic monuments in the world,2 an ancient civilisation has left extensive remains which include a short staircase. Simple rectangular blocks have been laid between solid megalithic block walls to form a staircase of some nine steps to connect two temples (Figure 1.1).

1.1 Early stone steps within the Tarxien temple and Saflieni Hypogeum complex, on the island of Malta, within a date range of 3800–2400 BC. The steps within the walls are mostly single blocks. There has undoubtedly been some restoration and reconstruction and the upper two steps, carved from a single block, are somehow unconvincing being much narrower – they may have been placed here from elsewhere. (David Davidson)

Early civilisations in Mesoamerica and Mesopotamia created grand stepped pyramids or ziggurats. Many such buildings incorporated ceremonial staircases, and the type, whether as tombs, for worship or other ceremonial purposes, were constructed over an enormous period of time, spanning some three millennia. The step mastabas or step pyramids of Ancient Egypt, although built in huge steps, did not have external staircases climbing to the top, although many incorporated internal staircases and ramps leading to tombs, as did the un-stepped pyramids. Particularly dramatic examples can be found at Ur, Iraq (2125–2025 BC) and in Mexico at Teopanzolco (1200–1521 BC), Tikal from c.800 BC, Cholula and Teotihuacan (Figure 1.2), both c.200 BC. Structurally, they are all extremely simple, consisting of bricks or stones cut to size and heaped up, one on top of the other.

1.2 Pyramid of the Sun, Teotihuacan 40 km west of Mexico City. (Michael Tutton)

Ancient Egypt and Ancient Greece

Egyptian temples had staircases often located in the entrance pylons. These were of stone or brick in straight flights within the massive outer walls, often consisting of the only internal space within the lower part of the pylon. They date from the First Dynasty (3100–2600 bc) onwards.3 They are to be found, for example, at the Temple of Khons at Karnak, 1200 BC and the Temple of Horus at Edfu, 237–42 BC. Egyptian houses had staircases, as evidenced by excavation, clay and wooden models found among grave goods and wall paintings. They ranged from single storey, often with an outside staircase to the roof, to two or sometimes three storeys. Many internal staircases were of timber carried on beams (carriage pieces) and had straight flights. The common external staircase to a roof terrace could be stone or brick.

Winding or spiral staircases are not so common in Egyptian architecture, but the earliest significant example, possibly as early as the Nineteenth Dynasty (1307–1196 BC), is at the complex of temples at Deir el-Medina. They became more widespread later, with examples at the pylon at Edfu, along with the other straight flight stairs and at the Egypto-Roman temple at El-Maharraqa.4 Along the Nile, spiral staircases were often constructed to form wells or Nilometers, to measure the height of the Nile. They first appear from c.760 BC and continue to be built into the Roman era. There is a fine example at Kom Ombo.

Invention of the cantilevered stair

Among the most remarkable spiral staircases of antiquity are those to be found on the islands of Naxos and Andros in the Cyclades. Here the remains of two remarkable staircases, both of the Hellenic period (500–300 BC), survive within circular towers. These staircases are cantilevered, set into the outer walls of the tower and without visible support to the internal open well.

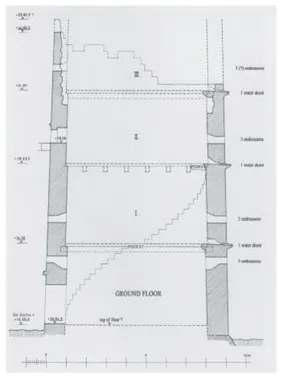

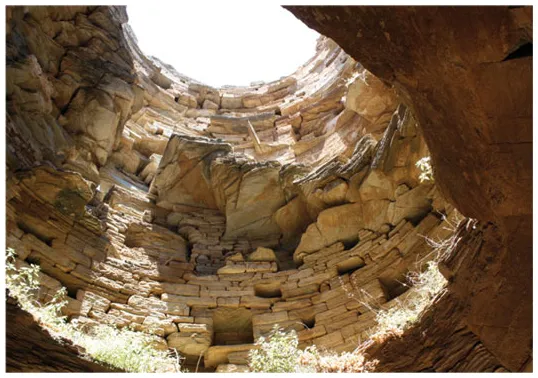

The tower on Naxos at Pyrgos Chimarrou is built of local marble and stands approximately 15 m high, although the top part has collapsed.5 Internally, the remains of a marble staircase rise clockwise with treads embedded in the wall (Figure 1.3). The tower of Agios Petros on Andros, some 2 km inland from the town of Gavrio, is more impressive. It stands 20 m high and is built of local schist. The dramatic spiral staircase starts at the first-floor level, where there is a doorway or window in the wall but no immediately obvious access from the ground. A doorway at ground level gives onto a circular vaulted room, the top of which has collapsed thus giving a view of the staircase rising up through the tower (Figures 1.4–1.5).6

1.3 Pyrgos Chimarrou tower on Naxos. Schematic section and partial reconstruction. (Lothar Haselberger, 1972)

1.4 Remains of the cantilevered staircase in the tower of Agios Petros on the island of Andros. Taken from the ground-floor vaulted room through the collapsed crown of the vault. (Michael Tutton)

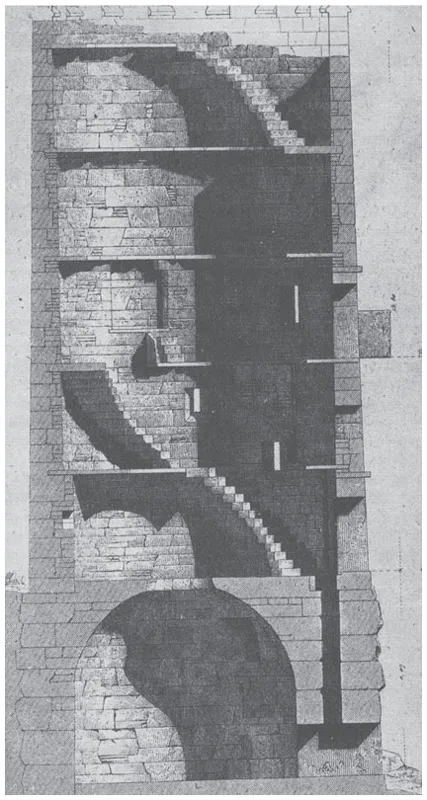

1.5 Engraved section of the tower of Agios Petros on the island of Andros c.1843, after a drawing by E. Landron in Le Bas and Reinach, 1888. Access to the first floor internally is via the shaft through the lintel of the lower doorway.7 The representation is not entirely accurate and the machicolations are Landron’s own interpretation, this being an ancient Greek building, not a Medieval one.

Both of these are spiral cantilevered staircases and such staircases may have been common. The tower of Agia Triada on the island of Amorgos, an oblong tower, contained several staircases in straight flights, the surviving remnants of which ‘are cantilevered monoliths projecting from the west wall’s inner face’.8 Similar round or square towers of the same period were widely distributed throughout the islands and the Aegean. Some 150 have been identified, mostly contained within the inner group of the Cyclades islands. Others have been found elsewhere in the Ancient Greek world, including Attica, Asia Minor and the Crimea.9 At ...