![]()

Chapter 1

Supervision past, present and future

This chapter tracks the evolution of CBT supervision from its roots in traditional generic supervision to its contemporary mandate to translate and disseminate efficacious treatments into effective treatments in routine practice. The chapter begins by detailing the ways in which CBT supervision is similar to generic supervision and how, to a degree, both mirror treatment. However, CBT supervision can be distinguished from generic supervision by the former’s appeal to a mediational model, in which responses to stimuli are mediated by cognition. The focus of the next section is then on the cognitive model of human behaviour. Within CBT ‘cognitions’ can be conceptualised differently and this has led to a variety of treatments, and the following section indicates that a different expertise (a particular set of knowledge and skills) is required of a supervisor for the different modalities sheltering under the CBT umbrella. Despite these differences there is a common structure to all CBT supervision sessions and this is elaborated next. Whilst there has been much theorising about what constitutes good CBT supervision and supervision in general, there are important question marks about whether, as currently practised, supervision positively affects client outcomes in routine practise and this issue is addressed next. This is followed by a focus on the practical difficulties of a supervisee acquiring a credible supervisor. In the context of a ‘not proven’ verdict about traditional CBT supervision, a revised model of CBT supervision is presented in which the supervisor is viewed as a conduit for evidence-based treatments. In turn this re-conceptualisation leads to viewing front-line clinicians as tasked with delivering EBTs (Evidence Based Treatment). The penultimate section of this chapter therefore suggests that ‘scientist practitioner’ is a poor descriptor of the front-line clinician’s daily practice and that they are more akin to ‘engineers’, whilst CBT therapists who are academic clinicians funded primarily by a university are ‘scientists’. The biggest challenge facing CBT is dissemination and, as at the time of the industrial revolution, it is engineers who are poised to make the leaps forward. The cultures and needs of scientists and engineers are different, neither must be subservient to the other, but able to draw on each other’s expertise, such that there is often a degree of overlap between scientists and engineers but they are substantially different. This new conceptualisation of supervision does not sit easily with a supervisee who wishes to ‘pick and mix’ amongst the CBT therapies or sees no value in diagnostic labels and these issues are addressed in the final section.

Commonalities between CBT supervision and generic supervision

CBT supervision draws on the components of generic supervision. Below is a typical generic pro-forma used by NHS Trusts in the UK:

Table 1.1 serves as a useful reminder of necessary components of supervision. Just as a client has to be ‘safe’ in therapy, so too a supervisee has to be ‘safe’ in supervision. Without safety the supervisee’s learning is compromised and they may not feel free to volunteer their feelings or have an open dialogue with their supervisor. There is a power differential between the supervisor and supervisee and therefore personal boundaries need to be put in place such as proscribing an intimate/sexual relationship. Professional boundaries mean that the supervisee should not be treated as a client if they volunteer material suggestive of a problem, rather it should be dealt with in the context of the impact on the client.

Table 1.1 Generic template for monitoring the effectiveness of supervision

Was a supervision contract agreed at the beginning of the supervision period? | Yes | No |

Is there a written record of supervision sessions? | Yes | No |

During supervision in the last. … . … . … …(insert time period), I have: | | |

| Yes | No |

Reflected on my practice | | |

Explored ways of working with particular service users | | |

Explored the dynamics between myself and service users | | |

Discussed the effect of my work on my own feelings | | |

Received constructive feedback on my work | | |

Felt validated and supported as an employee | | |

Reviewed my workload | | |

Discussed my professional development | | |

Had opportunities for learning new skills or developing existing ones | | |

Felt able to raise aspects of my work which I don’t feel confident about | | |

Discussed my relationships with colleagues | | |

Supervision has helped me in the following ways: | | |

As part of my supervision I would have liked: | | |

Elements of supervision that have not been useful: | | |

The supervisor–supervisee relationship may be formalised by contracts; see Appendix A for an example contract (Sloan, 2005). Unfortunately, the need for such contracts only becomes readily apparent when something goes wrong, such as a supervisor disclosing to a Manager some information about the supervisee that is not simply about the latter’s output. The supervisee may then believe that they can no longer trust the supervisor. But there should also ideally be a contract between the supervisor and the Organisation/Manager which also specifies the boundaries of confidentiality. The contracts can then be an important reference in any dispute or areas of concern. The supervisor has responsibilities not only to the supervisee but also to his/her funding body and unless there is clarity about how the dual responsibilities are to be discharged one or other party may well be aggrieved. Whilst the contracts do necessarily have a legalistic flavour, nevertheless they serve as an important reminder to all parties, of the framework they should be operating in and may have a preventative function.

It is important that supervisor and supervisee agree in advance that supervision sessions comprehensively cover all the supervisee’s work, not just for example those cases that are going well. Having sessions videoed can act as some protection against selectivity, but the cases selected for scrutiny can themselves be selective.

Supervision a mirror of treatment?

There are undoubted similarities between supervision and the treatment of a client in that supervisees (like clients) inevitably have different levels of experience and education and both require a tailoring of supervision/treatment to their needs. For example one supervisee may have a psychodynamic/humanistic background, another may not; unwittingly in the former the supervisee is likely to raise issues like secondary gain which do not fit easily into a CBT framework and supervision will have to address this issue. In other instances there may be a major cultural/ religious gap between supervisor and supervisee, just as there may be a similar gap between therapist and client; in both cases there is a need to understand the nuances of the assumptive world of the other. For the supervisor/therapist this may mean a need for dialogue with a colleague from the same culture/religion to avoid a stereotypical reaction.

Although CBT supervision has mirrored treatment there are important differences between them, see Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Differences between supervision and treatment

| 1. Supervision is not usually of limited duration. 2. Supervisees do not present with readily identifiable ‘deficits’, in the way clients may present with specific disorders. 3. The focus of supervision with a supervisee is likely to be on a much wider range of disorders than the disorders suffered by any one client. 4. The focus of supervision is likely to range beyond any one CBT treatment modality. 5. It is assumed that a treating clinician has an expertise in treating the disorder that the client presents with but it is unlikely that the supervisor has an expertise in all the areas that might concern their supervisee. 6. The psychosocial environment of the supervisee will not usually significantly impair functioning in the way a client’s does. 7. The supervisor and supervisee usually have a joint responsibility to a third party. |

Supervision, outside of the context of training establishments, such as the Beck Institute, is not time limited; as such there is no beginning, middle and end. Because of the open-endedness of routine supervision it is probably easier for sessions to ‘drift’. By contrast the novice therapist in time-limited supervision usually progresses from structured manualised treatments to a greater emphasis on formulation informed practice by the end of supervision, from a more didactic input from the supervisor initially to the therapist deciding on and evaluating therapeutic experiments, accompanied by reflective commentary from the supervisor.

Supervisees do not ordinarily present with an emotional disorder/problems in living as a prime focus, so whilst a supervisor may provide support in such instances there would be a confusion of roles if the supervisor were to treat the supervisee. This is not to say that a supervisee may not have cognitions that interfere with the delivery of CBT and which would therefore become an appropriate focus in supervision. Common dysfunctional cognitions of novice therapists include: ‘I shouldn’t feel irritated by the client’, ‘I have got to get each session right’, ‘I must avoid making the client uncomfortable’. The first step is making these maladaptive attitudes explicit to the supervisee and the second step is re-appraising these attitudes by questioning, variously, their utility, the authority by which they are held and their validity. In some instances supervisees may be undergoing CBT supervision more as part of their job description rather than from a whole-hearted endorsement of CBT. Supervisees’ reservations about CBT can include ‘it’s mechanistic’, ‘doesn’t take proper account of historical material’, ‘leaves little room for emotion’, ‘people are more than computers’; such mal-adaptive attitudes need to be addressed in supervision if the full potency of CBT is to be released.

The breadth of discussions in supervision is likely to be much broader than the focal concerns in relation to any one client. The supervisor will inevitably have gaps in his knowledge base and limited practical experience of working with particular client groups but should be able to signpost the supervisee to suitable repositories of such knowledge and experience. Given the range of practice contexts of supervisees the supervisor will need to be able to go beyond Beckian cognitive therapy and should have at least a familiarity with other cognitive behaviour therapies, for example Self-instruction Training (Meichenbaum, 1985) – which would be more appropriate for a client with mild learning difficulties – or Problem Solving Therapy (Nezu and Nezu, 1989) for parasuicidal clients. Further, because of the need to disseminate CBT, it is incumbent on supervisors to acquaint themselves with low intensity interventions and group work to enable supervisees to advance these cost-effective modalities (see Scott, 2011).

What is distinctive about CBT supervision?

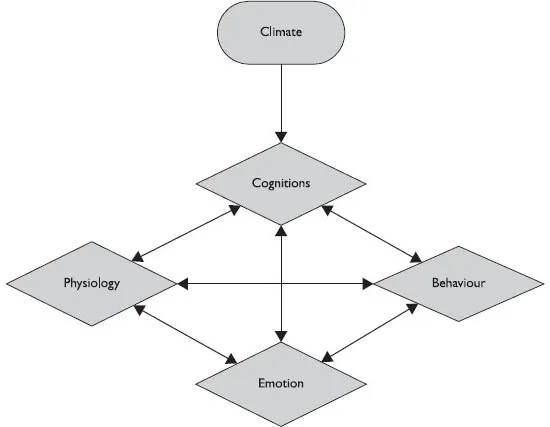

CBT supervision can be distinguished from other forms of supervision, in that it is based on the CBT philosophy of the reciprocal interactions of cognitions, behaviours, emotions and physiology, see Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 The Cognitive Behaviour Therapy model.

Thus a client’s emotional state may be altered via any of the four ports of entry, cognition, emotion, behaviour or physiology in Figure 1.1, for example if the client was tense they might go for a walk, this would be an example of making a change via the physiology port. But Figure 1.1 also indicates that a client’s emotional state is influenced by the climate that they are in, e.g. if the client has a highly critical partner this might dissuade them from going for a walk to unwind. For ease of illustration the climate is shown as operating via cognition, but in fact it exerts its effects through each of the four ports in the bottom part of Figure 1.1.

The therapist can also be thought of as operating via the climate in Figure 1.1, at some points in a treatment session acting via the cognitive port, when engaged in, say, Socratic dialogue with the client; at other times acting via the behavioural port when engaged in, perhaps, therapist-assisted exposure; in other sessions entering via the physiology port, with applied relaxation, for example. The ports of entry for the therapist are not meant to be mutually exclusive; for example, the therapist might prepare the way cognitively for the replacement of one emotion, e.g. depression, with another emotion such as anger.

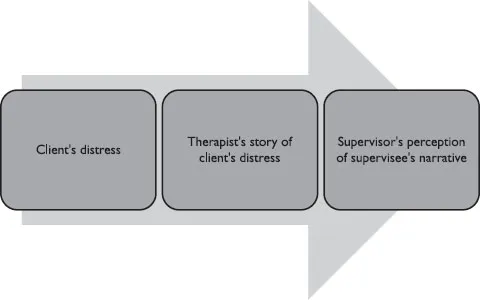

Both supervisor and supervisee exist in the climate cloud of Figure 1.1 and their experiential transactions can affect the client’s emotional state below. However the client’s emotional state can also affect the supervisee and usually indirectly the supervisor, see Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2 The translation of client distress to the supervisor.

The climate that exists between the sup...