![]()

1 ‘No man’s land’ and the creation of partitioned histories in India/Pakistan

Pippa Virdee

The point of departure by Britain from its most prized colony, India, resulted in one of the most violent episodes of the twentieth century, subsequently uprooting an estimated fifteen million people. This was the result of unprecedented levels of communal violence, which contained elements of both spontaneity and planned ethnic cleansing. The dislocation was at its peak in the Punjab between August and December 1947. The majority of the migrants came from the Punjab, Sind, North West Frontier Province and Bahawalpur State on the Pakistani side, and from the East Punjab, the East Punjab States, Delhi and the United Provinces on the Indian side. Bengal, on India’s eastern border, was also partitioned with the creation of East Pakistan (contemporary Bangladesh), but levels of violence were lower. Forced migration in Bengal was on a much smaller scale, although it was drawn out for many years (Chatterji 2007; Talbot and Singh 1999). The violence, which prompted this mass forced migration, resulted in an estimated death of one million people, mostly during the immediate weeks following independence in August 1947. But as Pandey in Remembering Partition points out, the debates on the levels of violence and casualties are bound by ‘rumour’ rather than verifiable truths (2001: 91). The longer-term legacies of this violent beginning in the form of strained relations between India and Pakistan have in many ways overshadowed the trauma and dislocation felt by millions of innocent people, who were forced to flee their homes. The loss of ancestral homelands for millions of people continues to resonate even today for the communally reconfigured Punjabi nation in West (Pakistan) and East (India) Punjab and among the diaspora.

This chapter first contextualizes the background to the violence and migration that accompanied independence and Britain’s departure from its ‘jewel in the crown’. It then discusses remembrance of these events as reflected in the main controversies among scholars surrounding the nature of the violence, the number of casualties and, more recently, to what extent partition-related violence should be considered genocide and/or a form of ethnic cleansing. Next, it considers the ways in which literature and film have represented partition and debates over a peace museum and a memorial. Finally, this chapter considers the ways in which oral testimonies have been increasingly used to delve into the human cost of partition and considers the legacy of partition in conserving a re-imagined Punjabi community in the subcontinent and among the diaspora.

Introduction

As independence from British colonial rule drew closer and the idea of a separate homeland for India’s Muslims became a reality, Punjab, a province which the leader of the Muslim League, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, termed the ‘cornerstone’ of Pakistan, effectively became the battleground. The British government put forward the 3 June Plan (Indian Independence Act 1947) that accepted the partition of Punjab and favoured a two-state solution to independence. Punjab was unusual because it comprised three main communities: Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims. Table 1.1 provides an overview of the religious composition in pre- and post-partition Punjab. While the 1941 census shows that Muslims were the majority community, in reality this varied across the province, and areas in central Punjab were the most mixed. Moreover, the 1941 census was unreliable because it was done under wartime conditions. It subsequently became a source of tension when minorities put forward their claims to the Boundary Commission (Chester 2009). Historically, Punjab had always had a strong pluralist and composite cultural tradition that statistical data and simple religious categorization do not reveal (Bhasin-Malik 2007). It was also – quite significantly – the spiritual homeland of a small but significant Sikh community, which added further complexity at the time of partition.

Table 1.1 Religious composition of population in Punjab, 1941 and 1951

| 1941

United Punjab | 1951

West Punjaba | 1951

East Punjabb |

Total population | 34,309,861 | 20,651,140 | 17,244,356 |

Hindus | 29.1% | 0% | 66% |

Muslims | 53.2% | 98% | 2% |

Sikhs | 14.9% | 0% | 30% |

Christians | 1.5% | 0% | 1% |

Others | 1.3% | 2% | 0% |

Sources: Census of India (1941 and 1951), Government of India and Census of Pakistan (1951), Government of Pakistan

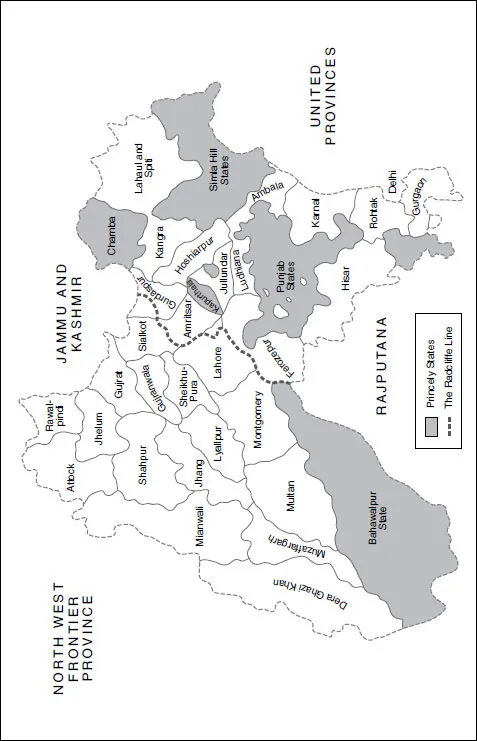

Based on outdated maps and census material, the barrister Cyril Radcliffe, who had no previous experience with South Asia or cartography, was given the responsibility of drawing the partition line in six weeks. Radcliffe arrived in India in July 1947, and although he complained of the short timeframe, the Boundary Commission reached its decision just days before independence and determined the fate of millions of people. To make matters worse, even though India gained independence on 14 August 1947 and Pakistan was created on 15 August 1947, the actual boundary between the two countries was not announced until 17 August 1947 (Chester 2009; Yong 1997). No prior notice was provided to the people who were still uncertain about which side of the border they would be on. During the months between August and December 1947, almost all the Sikhs and Hindus of West Punjab left Pakistan to create new homes in India and similarly nearly all the Muslims of East Punjab (and many from adjoining areas) left India to create new homes in the Dominion of Pakistan.

There was evidently a lack of foresight and leadership as British rule came to an end. The British administration was keen to exit as soon as possible to avoid being embroiled in a prolonged civil conflict, while the newly created states of India and Pakistan were too focused on the endgame to foresee the repercussions of partition, especially in terms of migrations, but also in terms of the economic consequences of division. The engulfing violence in the province forced many people to flee their homes, which in turn meant more people were forced out to make space for the incoming refugees. It was clear to the leadership that events had spiralled out of control; they forced the leaders of India and Pakistan, Jawaharlal Nehru and Liaquat Ali Khan, respectively, to issue a joint statement at the end of August 1947:

The Punjab was peaceful and prosperous only a short while ago. It is now witnessing scenes of horror and destruction and men have become worse than beasts. They have murdered their fellow beings with savage brutality and have spared neither women nor children. They have burnt houses and looted property. Even people fleeing in terror have been butchered. … Both Government (sic) are thus devoting all their energies to the task of restoring peaceful conditions and protecting the life, honour and property of the people. They are determined to rid the Punjab of the present nightmare and make it at (sic) once again the peaceful and happy land it was.

(Singh 2006: 508)

The full statement is aimed at restoring order and giving the impression that the respective governments are in control of the situation. However, even when law and order was restored by early 1948, the official, state-sponsored history of this period has tended to celebrate the achievement of independence and play down the dislocation surrounding partition, displacing blame for the violence. The new states could hardly admit to failing to be able to protect minority citizens at the outset of their existence. Hence, they played down the violence and later trumpeted successful refugee rehabilitation to boost state legitimacy. The Indian nationalist approach led by individuals like V. P. Menon (a political insider and constitutional adviser to the last three Viceroys during British rule in India) was to interpret partition as the net result of years of divisive policies adopted by the colonial power, which undermined pre-existing cultural unities and social interaction that had cut across religious identity (Menon 1985). The Pakistani perspective is epitomized by politicians like Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman (Governor of East Pakistan, 1953–1954), who in his memoir, Pathway to Pakistan (1961), argues that the creation of a separate homeland was necessary in order to safeguard Muslim rights and interests. The ideologically incompatible discourses arising from the Indian ‘divide and rule’ and the Pakistani ‘two-nation theory’ understandings of partition following independence have often obstructed the remembrance of partition.

Map 1.1 The Radcliffe Boundary Line

Source: Pippa Virdee.

Scholarly divisions, debates and controversies

There are a number of problems associated with the study of partition-related violence. These concern the extent to which it was spontaneous or planned, the degree to which any localized case studies can form part of a broader historical narrative, and the extent to which partition violence differed from ‘traditional’ communal violence (Das and Nandy 1986).1 These issues also raise the question of the extent to which the concepts of ‘ethnic cleansing’ and ‘genocide’ are useful in understanding the events that took place in Punjab. These concepts are still relatively new in the study of partition, but they are important in the wider historiographical context. In recent research, writers such as Talbot (2007), Hansen (2002) and Brass (2003a) have attempted to bring the Punjabi experience into the main literature on genocide, which has been largely dominated by the Holocaust partly perhaps because the contemporaneous events in Europe overshadowed those in Asia. More controversially, it could be argued that there is even a ‘hierarchy of suffering’: when we consider the vision of ‘the emaciated women and men liberated from concentration camps’ (Lal n.d.), anything else would become invisible in comparison with these shocking and disturbing images.

At the most basic level, there is a dispute concerning the number of casualties arising from the partition-related violence; estimations vary considerably. It is in reality an impossible task to ascertain precise figures, and hence numbers have varied to suit political objectives. Indian nationalist writers have tended to lean towards the higher end of the spectrum while British writers have tilted towards the lower end. In Pakistan, the casualties represent the price of demanding a separate state from the domineering Hindu majority. This is hardly surprising as successive governments in both India and Pakistan have emphasized the problems their new states were able to surmount, while British governments have wished to preserve a legacy not marred by scenes of disorder.

The debate surrounding the number of casualties is longstanding. It was still a concern to Lord Mountbatten, even years after he had relinquished the office of Viceroy of India. In a letter to Penderel Moon (a British civil servant), written on 2 March 1962, he declared that he was ‘keen that an authoritative record should be left for the historians long after I am dead …’ even though he was neither particularly keen on defending himself at this stage ‘nor [on] joining in the argument’ (Letters on Divide and Quit). The following extract from a letter sent by Mountbatten to Moon on 2 March 1962 highlights the inconsistency surrounding the casualties.

My estimate has always been not more than 250,000 dead; and the fact that your [Moon] estimate is not more than 200,000 is the first realistic estimate I have seen. I have often wondered how the greatly inflated figures which one still hears were first arrived at, and I think that they were due largely to the wild guesses which were made in those emotional days after the transfer of power. That they still persist is very clear; for example, Mr Leonard Mosley’s latest book2 gives, I understand, the figure of 600,000, and only the other day a backbench conservative MP told one of my staff that the figures were [sic] three million!

(Letters on Divide and Quit)

In 1948, G.D. Khosla, who became Chief Justice of the East Punjab High Court in 1959, led the Fact Finding Commission by the Government of India to refute the Pakistani charge of genocide against Muslims emerging from United Nations debates over the Kashmir conflict (Tan and Kudaisya 2000: 253). Khosla wrote Stern Reckoning shortly after this, in which he estimates the number of casualties to be around 200,000 to 250,000 non-Muslims and probably an equal number of Muslims, bringing the total to nearly 500,000 (1989 [1949]: 299). The historian Patrick French (1997) contends that deaths numbered closer to one million. In a recent interview, the Indo-Canadian writer Shauna Singh Baldwin suggested the figure of five million (Rajan 2011). Many of the police records were destroyed during the disturbances, and due to the lawlessness of the state at the time, the records that do exist are unreliable in providing a comprehensive picture. Furthermore, it is difficult to calculate and differentiate between those who died directly due to the violence and those who died during the mass exodus, through starvation and disease. The truth in reality will never be known because it is an impossible task; as Pandey (2001: 91) suggests, casualty numbers are based on rumour and repetition, both of which continue to reverberate.

Anders Bjorn Hansen has argued that the intentions, intensity and degree of organization of the violence by communal groupings warrant the violence in the Punjab to be understood as a manifestation of genocide (2002). Interestingly, partition violence has not traditionally been incorporated into broader accounts of genocide or ethnic cleansing as we understand these terms today. Recent literature such as Centuries of Genocide (Totten and Parsons 2013) continues to overlook the massacres that took place in Punjab in 1947, as does Mann’s analysis (The Dark Side of Democracy, 2005) of ethnic cleansing. One explanation for this omission is that the term has been deployed in relation to the Holocaust and the post-Cold War violence in the Balkans and Rwanda. This raises the question of whether it is appropriate to apply this term retrospectively to events that took...