eBook - ePub

Booker Tropical Soil Manual

A Handbook for Soil Survey and Agricultural Land Evaluation in the Tropics and Subtropics

- 530 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Booker Tropical Soil Manual

A Handbook for Soil Survey and Agricultural Land Evaluation in the Tropics and Subtropics

About this book

First published in 1991. This is a more portable version of the Booker Tropical Soil Manual, in which the format (and weight) of the first edition have been reduced whilst retaining as much as possible of the original clarity. It also includes new content and appendices that cover the revised FAO publications on soil classification and on water quality for agriculture.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Aims and scope of the manual

This manual stems from many years’ work by BAI on agricultural consultancy and management assignments and reflects the need felt by staff members for a concise, comprehensive – and above all readable – summary of soil-related methods and terminology, with clear guidelines for interpretation of soil and land evaluation data used in project design, costing and management. The manual therefore has two main aims: it is intended firstly to be a practical source-book for soil scientists in the field, and secondly to be a reference work on soil and related studies for members of other disciplines who require information for purposes such as proposal compilation, project planning, survey implementation and practical interpretation of soil and land capability reports. It is not intended as a replacement for the standard soil survey manuals, but rather as an expansion of particular topics of most immediate use for consultancy assignments in the tropics and subtropics. The contents also reflect the working practices of BAI, and are thus fairly strictly confined to those aspects of development studies handled by soil scientists as members of multidisciplinary teams. The manual does not, therefore, cover the wider aspects of multidisciplinary investigations, which are treated in, for example, ILACO (1981), Shaxson et al (1977) and Ministére de la Coopération (1974).

1.2 Selection of contents

The contents of the manual are not intended to form a ‘balanced’ work on soils and land evaluation. Instead, the main emphasis is placed on those items which receive scant attention in published works (such as numerical values for critical levels of soil constituents) and on those which are treated in too many sources and need amalgamation to be of practical value (such as methods in soil physics). The presentation also reflects the preferences of BAI soil scientists in the level of detail accorded to different systems and methods. In most cases a recommended practice is covered in some depth, whereas less suitable or less convenient methods are only summarised, although full references have normally been included. Items such as soil morphological descriptions are treated only superficially in the manual, since they are dealt with more fully in well-known references that would usually be available on site during projects.

Other inclusions or omissions arise as a result of the division of responsibilities between specialists of different disciplines within BAI, or are a reflection of the range of projects that the company normally undertakes; specific omissions, with some suggested references, are as follows:

Quantitative and numerical methods, including soil information systems, automated mapping, spatial and statistical analyses

(de Gruijter, 1977; Webster, 1977; Burrough, 1982, 1986)

Land surveying for soil studies

(Wright, 1982)

Soil and land evaluation for tree crops or forestry

(Chan Huen Yin, 1980; Pritchett, 1979; World Bank, 1980; Laban, 1981)

Soil pollution

(D’ ltri, 1977; Harmsen, 1977; HMSO, 1979; Davies, 1980)

Soil engineering

(Terzaghi and Peck, 1948; Jumikis, 1967; Lambe and Whitman, 1969; USBR, 1974; BSI, 1981; Brink et al, 1982)

Economic evaluation

(Bergman and Boussard, 1976; Irvin, 1978; Gittinger, 1981)

Climatic analysis

(Troll, 1966; Money, 1974; Doorenbos and Pruitt, 1977)

Hydrological studies

(FAO series of Irrigation and Drainage Papers)

Soil biology and microbiology

(Kononova, 1966; Phillipson, 1971; Wallwork, 1976)

Ecology and environmental impact

(Odum, 1964; Walter, 1971; Golley and Medina, 1975; Unesco series of Man and the Biosphere Papers)

Land management techniques

(Hudson, 1975; Schwab et al, 1966; Greenland and Lal, 1977; in Africa Allan, 1965 and Upton, 1973)

Wherever possible the subjects covered have been quantified and numerous rules of thumb are included in the manual. The numerical values are mostly for use at the prefeasibility or feasibility levels where other data, and particularly crop trial data, are lacking. Most of the values are described as ‘tentative’ or ‘indicative’, since it would be impossible in a book of this size to summarise all the effects and interactions, even if they were all known. The figures do, however, serve a useful purpose in helping to warn of potential problems which could appear during project implementation, and which should therefore be allowed for in project designs and costings. There is a certain amount of repetition in the book, and frequent cross-references are included; this is deliberate, to facilitate use of the manual as a reference book for specific topics.

1.3 Layout of the manual

The main text of the manual is aimed primarily at the non-specialist land resource assessor, and the Annexes at the specialist soil scientist. The main text is compiled roughly in the order the information is needed in most consultancy projects, but with general aspects preceding the more detailed and specialised sections, a format which is paralleled within individual chapters. Discussions of survey planning and organisation thus form the opening sections followed by an outline of soil classification and land evaluation. These are followed in turn by chapters on specific soil physical and chemical measurements and their interpretation, before a final chapter on reports and maps. Great emphasis is placed on the collations of physics and chemistry interpretive data (Chapters 6 and 7 take up 100 pages, more than half of the manual’s main text) because the BAI experience is that these topics tend to be scattered amongst references and sources, or treated cursorily or from viewpoints other than the soil surveyor’s in the general textbooks.

The set of 15 Annexes contain more specialist information, mainly of interest to practising soil scientists; they include numerous checklists and worked examples for planning and execution of soil surveys and related studies.

1.4 The need for soil surveys

The importance of soil and land suitability studies for agricultural development projects has long been recognised by their proponents, such as soil surveyors and land use planners, but even today many workers in other disciplines still tend to regard such studies as being, at best, of only peripheral value to their work. All too often only a fraction of the potentially important information contained in a soil report is used, the remainder being considered too academic, too riddled with incomprehensible jargon or too remote from the practical decisions and actions which are needed for successful development and management of agricultural enterprises. In general, this under-use appears to be the result of a ‘communications gap’ between producers and users of soil reports, since the importance and relevance of soil-based studies have often been stressed. Storie (1964), for example, quoted in FAO Soil Bulletin No 42 (1979a), lists 11 major areas in which soil and land evaluation studies can contribute significantly to irrigation developments. In most projects, soil and related studies should form an indispensable part of the basic planning process (see Chapter 2), and without them very costly mistakes can be, and have been, made.

All too often the perceived expense of soil survey and land evaluation means that such work is skimped or even omitted from project planning, but the costs need to be seen in relation to the overall development of a project. Young (1973) indicates that a survey can pay its way if it prevents planting of unsuitable land over as little as 10% of a project area, and Nieuwenhuis (1975) suggests that soil surveys typically take up only 10 to 20% of planning costs which themselves form only about 10% of total project development costs. As a rough guide to the quantities involved, the figures of Dent and Young (1981) are illustrative: reconnaissance field surveys can be made relatively cheaply at costs of the order of £10 knr2, and semi-detailed surveys for about 5 to 10 times that, at £50 to £100 km−2. Depending on soil complexity and the intensity of field-work required, more detailed surveys down to scales of about 1:25 000 can be about three times more expensive, and 1:10 000 work some three to four times more expensive still, with costs of about £500 to £1 000 km-2.

Using again the example of Dent and Young (1981) with slightly amended figures, a survey for rainfed development at 1:25 000 could cost about £2 ha−1, an area with a yield potential of some 2 t of grain valued at £200 on the world market. Assuming the effects of the survey raised net gains by a modest 5%, the produce value would increase by about £10 ha−1, or five times the survey cost, in a single year. In appropriate circumstances, therefore, soil surveys can be highly cost effective, provided a careful choice is made of scale and intensity relative to the development envisaged.

Chapter 2

Types of Land Resource Field Studies

2.1 Introduction

The types of land resource surveys undertaken by soil surveyors attached to commercial companies can be categorised under one or more of the following headings:

a) Exploratory;

b) Reconnaissance;

c) Semi-detailed;

d) Detailed.

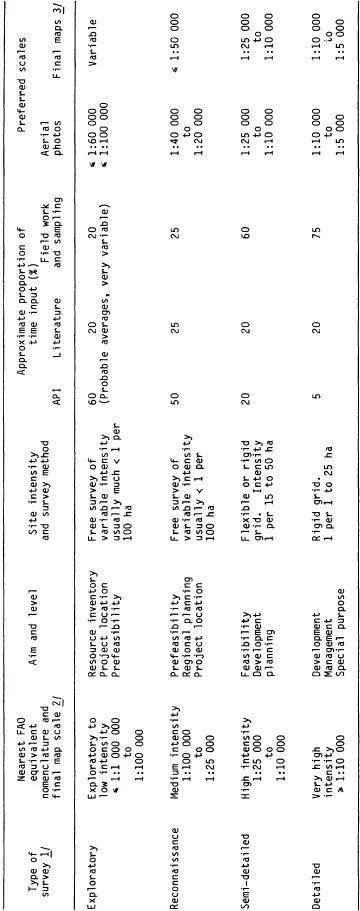

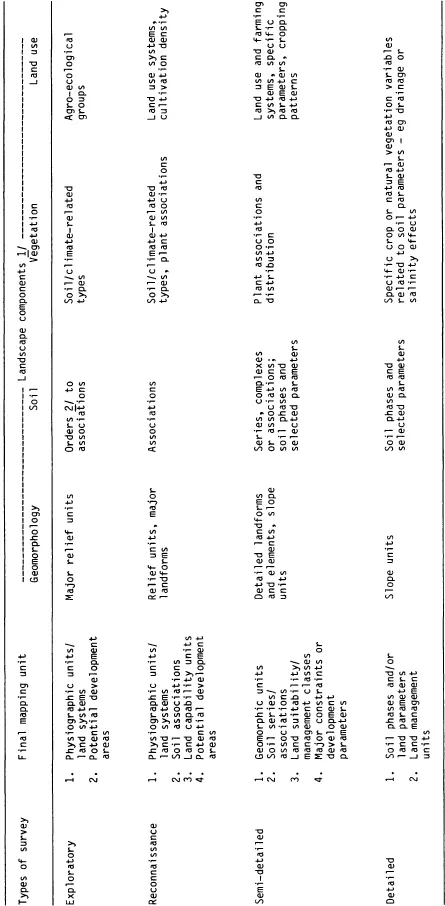

All of these terms are in common use, although there are wide differences in the definitions of the scales and intensities included under the individual headings. To avoid confusion, therefore, the purpose, intensity and scale of a survey should always be stated (see Tables 2.1 and 2.2). The descriptions that follow are particularly relevant to the projects undertaken by BAI; general definitions are given in FAO (1979a, p 88).

The more intensive the survey, the more detailed are the mapping units, the more direct are the measurements of the parameters mapped and, normally, the more specific is the purpose of the survey. The use of aerial photos or satellite imagery is correspondingly reduced with increasing scale and intensity of survey.

In small-scale surveys, and where soil/landform/vegetation relationships can be established, a soil surveyor can use free survey techniques, which involve the location of representative sites based on his own professional judgement. At larger scales, grid surveys are usually preferable, making the sampling more objective and, if the grid is randomly aligned, capable of statistical interpretation.

2.2 Exploratory surveys

The purpose of an exploratory survey is to obtain a rapid general appraisal of an area. Normally this is either to determine what further studies are required or to locate suitable sites for a specified development. The soil and land capability inputs to an exploratory survey will usually, therefore, form part of a broadly based study at the prefeasibility level.

Summary of types of land resource surveys Table 2.1

Notes:

1/ These terms are loosely used for a wide variety of intensities and final map scales: Chapter 3).

2/ See FAO (1979a, p 88).

3/ For many integrated projects the final map scale may be chosen to conform to civil engineering or project development requirements rather than to the most appropriate scale for the survey intensity and complexity of the soil pattern (see Subsection 9.5.1).

Summary of mapping units used in land resource surveys Table 2.2

Notes:

1/ After Baulkwill (1972).

2 ie the highest level of soil classification (see Annex C); not to be confused with the USDA term ‘order of soil survey’ Which refers to the kind of survey (see Orvedal, 1977).

...Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- LIST OF FIGURES

- LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- PREFACE TO THE PAPERBACK EDITION

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (1984 EDITION)

- 1 INTRODUCTION

- 2 TYPES OF LAND RESOURCE FIELD STUDIES

- 3 SURVEY ORGANISATION AND PRACTICE

- 4 CLASSIFICATION AND MAPPING OF SOILS

- 5 LAND EVALUATION

- 6 SOIL PHYSICS

- 7 SOIL CHEMISTRY

- 8 SOIL AND WATER SALINITY AND SODICITY

- 9 SOIL AND LAND SUITABILITY REPORTS AND MAPS

- ANNEXES A to Q

- REFERENCES

- INDEX OF AUTHORS AND OTHER PERSONAL NAMES

- APPENDIX I FAO-UNESCO SOIL MAP OF THE WORLD REVISED LEGEND

- APPENDIX II SOIL AND WATER SALINITY UPDATE

- SUBJECT INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Booker Tropical Soil Manual by J.R. Landon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.