![]()

1

Making Students Feel Valued and Capable

A group of six high school students from Dayton Business and Technology High School met with a researcher from the National Center for Urban School Transformation (NCUST). The researcher asked, “How did you happen to attend this school?”

One male student quickly responded, “Most of us were kicked out of other schools.”

Another male affirmed, “Yeah. We got expelled because of stuff.”

“So, how long will you attend this school?” the researcher asked.

“Oh, I’m not going back to my other school,” one girl quickly explained.

“Me either!” other students offered in chorus.

“Almost all of us plan on graduating from this school,” one of the girls explained.

“Is that because you’re not allowed to return to your previous schools?” the researcher asked.

“No,” one of the boys responded, while adding, “We could go back after one month, one semester, or one year, depending on what we did. But, we don’t want to go back. We want to graduate from this school.”

Before the researcher could ask why, one of the girls explained, “The teachers at this school care about us. They want us to learn.”

Another chimed in, “Yeah, they want us to graduate. They believe in us.”

“But, don’t all teachers care?” inquired the researcher.

“Not at my other school. At least, they didn’t care about me,” responded one of the boys.

“At this school, the teachers really want you to understand things,” one girl added.

“What do you mean?” inquired the researcher.

The girl responded, “At the other schools, the teachers just want to get done with whatever they’re supposed to do, give you an assignment, and give you a ‘D’ or ‘F’ grade. They don’t really care if you learn it or not. They just want a grade for their gradebook.”

“Yeah, but here it’s different,” another student explained. “They’re always trying to break it down for us so we understand it.”

“What do you mean?” the researcher asked.

The girl explained, “Like, they’re always trying to make it real for us. The teachers are always trying to make things make sense to us. They really want us to understand.”

After a brief pause, the researcher asked, “So, do you feel you work harder here than you worked at your previous schools?”

In unison, the students nodded affirmatively. Then, the researcher asked, “Why do you work harder at this school?”

One of the boys answered, “Why do we work so hard? Well, you know that most of us kids went to other schools around here, and we were kicked out or suspended or other stuff happened.” Then gesturing with his arms crossed, as if imitating his former teachers, he continued, “At my other school the teachers would see me coming and think ‘Here comes trouble. Here comes a headache. Here comes my next suspension. Here comes a dropout.’ They saw me as another Black statistic. Even though I knew I wasn’t stupid, I pretty much figured they were right. I was never good at school. I had a hard time reading the textbooks. I just didn’t see how I was going to get anywhere at school or in life.”

He continued to explain, “So, when I came here, I thought it would be all about hanging with my friends. But, when I got here, the teachers saw me differently.” Then gesturing with his arms wide open, he continued, “They looked at me like ‘Here comes potential. Here comes a future graduate. Here comes a future college student.’ That’s the way they treated me. That’s the way they talk to all of us. So, when you’re treated that way, it just makes everything different. You want to work hard because you want them [the adults] to be right about you. You don’t want them to change their minds.”

Dayton Business and Technology High School is a charter school in Dayton, Ohio. The school won the America’s Best Urban School Award in 2013.

A Perpetual Question

On the Minds of Educators Striving to Produce Equity and Excellence

How can I get each and every one of my students to believe, “My teacher sincerely wants me to succeed in life and my teacher is confident that I can succeed”?

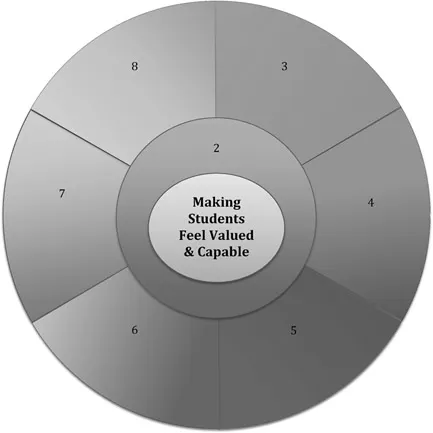

In schools where diverse groups of students excel, teachers lead all students to feel valued and capable. In the first edition of this book, we discussed this phenomenon as one of eight key teaching practices. However, after visiting and studying many more outstanding urban schools, we acknowledge the centrality of making students feel valued and capable to the other seven practices. Thus, Figure 1.1 illustrates that the practice of making students feel valued and capable is at the heart of the effective instructional practices we found in the high-performing urban schools we studied. Efforts to implement the other seven practices are less likely to influence learning results if they are not implemented in a manner that results in students feeling valued and capable.

Scheurich (1998) studied schools that generated strong academic results for children of color and children from low-income families. He determined that educators in those schools established caring, loving, and respectful environments in which students were expected to achieve at high levels. Similarly, in every high-performing school we studied, students (including students at the Dayton Business Technology High School referenced above) emphasized that their teachers cared sincerely about them and their academic success. We believe that almost all teachers care about their students; however, students in high-performing urban schools are much more likely to perceive that their teachers care about them and value them. The perception of caring, or lack thereof, influences student motivation and behavior.

Noddings (2005) emphasized that care and students’ perception of care were likely to influence student success. Ferguson (2002) specifically noted that Black and Latino students’ perceptions of their teachers’ caring influenced their level of effort even more than did White students’ perceptions of their teachers’ caring.

After visiting 150 high-performing urban schools where all demographic groups of students excelled, we are convinced that teachers in these schools lead students to feel valued, respected, and capable. In more typical schools, the same students are often left to feel alienated, unwanted, and unlikely to succeed. Teachers in high-performing urban schools convince Black, Latino, and Native American students, students from low-income or immigrant families, students with emerging bilingualism, LGBTQ students, students experiencing homelessness, students in foster care, students with disabilities, and many other students that the adults in the school value and respect them. Somehow, students (including students who are commonly not served well in urban communities) become convinced that their teachers are committed to helping them succeed in school and in life.

Throughout this chapter, we use the term “caring” extensively. We note, however, that Noddings (1984) and Valenzuela (1999) described “aesthetic caring” that occurs in ineffective schools where educators demonstrate “care” when students conform to educators’ expectations. The veneer of aesthetic caring wears thin quickly in environments where students are accustomed to the frustrations and disappointments associated with poverty, violence, and racism. In contrast, Noddings and Valenzuela explained that, through authentic caring, educators nurture and value relationships with all students. In this second edition, we have endeavored to distinguish the authentic caring we observed in the high-performing schools we studied. We have attempted to explain what authentic caring looks like and why this type of caring is difficult to develop and sustain.

It is important to emphasize that students in high-performing urban schools perceived that their teachers cared about them and they perceived that their teachers believed they were capable of succeeding. In contrast, Fisher, Frey, Quaglia, Smith, and Lande (2018) reported that 27 percent of students don’t think their teachers expect them to be successful. This percentage is likely higher among students served in typical urban schools. Among students who perceive that their teachers doubt their ability to succeed, only the most resilient or those with the strongest supports at home are likely to thrive academically. Thus, a central factor in the success of high-performing urban schools is their ability to create environments in which students perceive that they are both valued and capable.

Caring Enough to Know and Value Individual Students

Hattie (2009) synthesized over 800 studies of factors that influenced student achievement. He found that teacher–student relationships have a major influence on student learning, more powerful than most pedagogical practices. While this finding might not surprise many, Klem and Connell (2004) found a lack of urgency on the part of many educators to establish and nurture strong positive relationships with students, even in the face of growing evidence that such relationships influence student academic performance.

In our interviews and focus groups with hundreds of students from high-performing urban schools, students used the adjective “caring” to describe their teachers more than any other descriptor. Students used the metaphor of family more than any other to describe their school. “It’s like a family here. People care about you,” students explained.

A factor that influences positive teacher–student relationships is the extent to which teachers succeed in getting to know and understand the students they teach. Often, in urban schools, teachers come from different racial/ethnic, socio-economic, and linguistic backgrounds than the students they serve. Perhaps, in our typical pre-service and in-service teacher preparation programs, we underestimate the chasms created by these differences. Too often, educators graduate from teacher preparation programs assuming they will teach students who share their backgrounds, interests, curiosities, and motivations. Conversely, too often, educators graduate from teacher preparation programs with assumptions that urban students have dramatically different backgrounds, interests, curiosities, and motivations. Neither set of assumptions is an appropriate substitute for the time and energy necessary to get to know students and their families. The greater the social distance between educators and students, the more essential it is for educators to spend time getting to know who they have the privilege to serve.

Fisher et al. (2018) reported that only 52 percent of students believe their teachers know their name. Additionally, only 67 percent of students indicated that they feel accepted at school for who they are. The lack of personal connection and acceptance create major learning barriers for many students. In contrast, students at high-performing urban schools reported that their teachers cared enough to get to know them, to build relationships, and to establish bonds.

For example, at O’Farrell Charter School in San Diego, California, each teacher is assigned a group of students with whom he or she meets daily. Teachers get to know their “homebase” students, their social/emotional needs and strengths, and their families. Similarly, teachers at MacArthur High School in Houston, Texas, explained how school administrators took them on tours of the surrounding neighborhood so that teachers could learn more about their students, their families, and the real challenges students faced. Beyond the neighborhood tours, MacArthur administrators expected teachers to make regular phone calls to parents. While these calls might have been difficult for some teachers initially, teachers reported that they came to appreciate how many of the parents were eager to see their child succeed in school (Gonzalez, 2015).

At International Elementary in Long Beach, California, one of the teachers established a mentor program. Almost every staff person at the school serves as a mentor to a student. Teachers meet with their mentees weekly and talk about whatever the student wants to discuss. These and similar efforts help ensure that students feel valued.

When Rose Longoria was assigned to serve as principal of Pace High School in Brownsville, Texas, her first priority was to help her faculty build relationships with their students. She wanted to help teachers spend time getting to know the students. She asserted, “We need to understand our students. We need to build relationships. Let’s find out why they are struggling.” By encouraging teachers to dig deeper to understand the reasons behind student issues, the principal urged teachers beyond aesthetic caring and helped teachers learn more about the strengths, needs, hopes, and fears of students and their families. These...